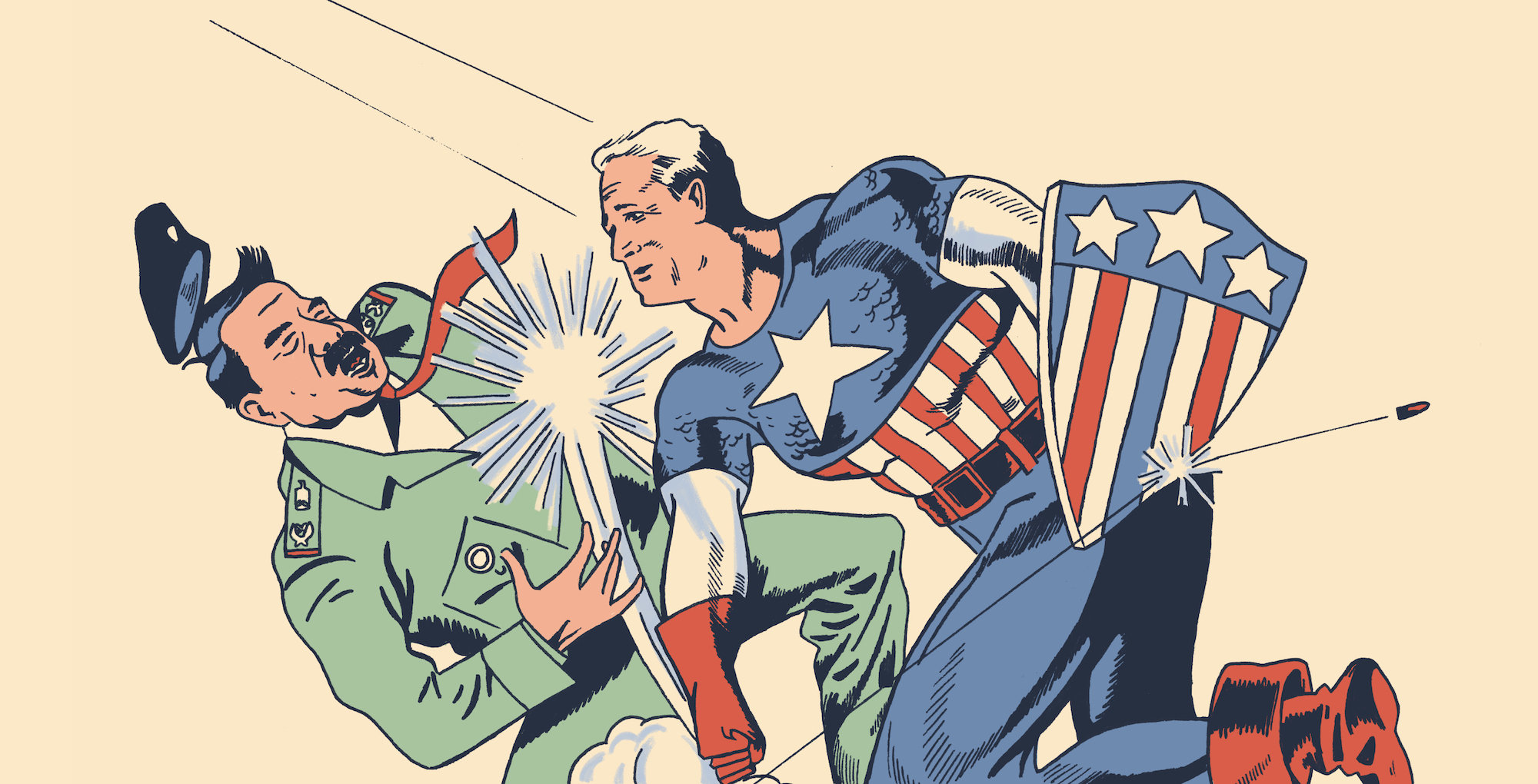

illustration by Brian Fabry Dorsam.

On December 20, 1940, Captain America threw one of the most famous punches in American history. Surrounded by Nazi soldiers, amidst an array of gunfire, Captain America smashed his fist across the face of Adolf Hitler, knocking him backward onto a file that read, “SABOTAGE PLANS FOR U.S.A.” Years before the United States entered World War II, Captain America stood up to fascism and anti-Semitism and secured his place at the moral center of America.

This is why the comic world shook in May when on the final page of “Captain America: Steve Rogers” #1, Cap uttered the unthinkable: “Hail Hydra.”

Since its creation, Hydra has been an analogue for Nazism, helmed not by Hitler, but by a fascistic, maniacal, red-skull-headed figure named, well, the Red Skull. Consequently, the revelation that Cap has been a deep-cover Hydra agent since childhood was shocking.

Captain America, much like the country after which he was named, has always been most clearly defined by his enemies. It’s when Cap throws a punch that we know what he stands for.

Hitler and the Red Skull embody the antithesis of American individualist morality — Cap’s morality — but they are Cap’s raison d’être. Fighting “anti-American” ideologies, like fascism, communism, and terrorism, gives Cap purpose.

With the words “Hail Hydra,” all of that changed.

Many readers have felt betrayed by writer Nick Spencer’s decision to reveal Cap playing for the wrong team. But Spencer is not the only one doing it.

The latest Marvel movie epic, “Captain America: Civil War,” offers a more carefully cloaked critique of Cap’s complex history and allegiances. When the United Nations passes an accord limiting the jurisdiction of the Avengers to U.N.-mandated missions, Cap refuses to sign. Despite the massive casualties incurred during multiple battles across the planet (see: literally any Marvel film), Cap swears off the accord and goes rogue, arguing that lengthy bureaucracy will cost more lives than it will save. He feels, ultimately, that the Avengers know best.

Civilian casualties, bucking the U.N., engaging in international conflict: Does this sound familiar? Captain America, in “Civil War,” bears more than a passing resemblance to George W. Bush.

It’s no coincidence that the renegade Avenger is the one in the American flag outfit. Cap’s blatant disregard for U.N. sanctions, his insistence on the use of violent force, and his penchant for intervening in international disputes make him a perfect analogue for Bush-era imperialist American politics.

President Bush infamously disregarded the U.N. to invade Iraq in 2003. Bush’s War on Terror quickly became an aimless, unsteady fight against an ever-changing, elusive enemy. These wars took their toll on the region, racking up thousands of civilian casualties and destroying infrastructural stability, all the while contributing to the creation of the Islamic State.

Of course, at the time, renegade military intervention had its detractors. In “Civil War,” Cap’s foil is Tony Stark, the tech genius who recently halted his company’s production of weapons of mass destruction and currently blasts bad guys as Iron Man. Stark grieves the casualties of the Avengers’ most recent campaign in the fictional country of Sokovia, argues for oversight, and fights to get Cap to sign the accord — to no avail.

Cap decides he would rather break up the Avengers than compromise his freedom. He fights his former teammates in an attempt to rescue a wanted terrorist suspect and ends up playing into the hands of a Sokovian colonel who orchestrated the collapse of the Avengers in retaliation for the death of his family.

In this way, the villain of “Civil War”, Colonel Helmut Zemo, turns out to be an avenger himself. By breaking up the Avengers, he dissolves what is, to him, a U.S.-sanctioned, interventionist terrorist group with a knack for accumulating civilian casualties. Zemo forces the audience to frame Cap’s patriotic punching in a new and unflattering way.

There is immense value in seeing a white man draped in an American flag become the enemy. The script must be flipped if Captain America is to remain the relevant political icon he once was.

Cap began as a Lower East Side, first-generation son of immigrants, who rose to greatness and took on the global enemies that his county refused to fight. Today’s Captain America is a vastly different figure. What critics have failed to recognize is that this isn’t because Cap is no longer the bastion of American morality; it’s because he still is.

Bush’s successor, President Obama, has been at war longer than any other president in American history. And with the country on the verge of electing Donald Trump, a candidate whose xenophobic platform has been likened to fascism, Hydra Cap rings appallingly true. While U.S. foreign policy has always been controversial, the negative effects of unregulated militaristic intervention and an imperialist model of democracy are more and more apparent.

The latest incarnations of Captain America illustrate the fluidity of the line between hero and villain. In an era of drone bombings, government surveillance, and a war that has caused over 150,000 civilian deaths, the myth of the star-spangled hero has already been rewritten. This country is no longer the country that punched Hitler. In fact, it never was.”