The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) presented a three-day lineup of Toshiki Okada’s newest play “God Bless Baseball” on January 28, 29, and 30. The play was part of the museum’s MCA: Stage program which hosts intimate theater productions at the Edlis Neeson Theater in Chicago. Okada is a celebrated Japanese playwright, writer, and stage director known for his use of unusual choreography. In “God Bless Baseball,” Okada uses the allegory of baseball — a sport popular in Korea, Japan, and the United States — to address the power dynamics between these three countries.

The play opens with the familiar American tune “Take Me Out to The Ball Game,” which suddenly morphs into the Mickey Mouse Club March. The audience hums the refrain: “M-i-c-k-e-y, M-o-u-s-e.” Two actresses walk on stage and begin fidgeting. They explain that they do not really understand the rules of baseball and thus have a lot of questions about the sport. (The characters are unnamed in the play so I will refer to them by their actual names.) One character portrayed by Sung Hee Wi speaks in Korean. At the same time, there is a projection of English and Japanese subtitles on one of the blackboards on both sides of the staged baseball diamond. While the other actress played by Aoi Nozu speaks in Japanese, English and Korean subtitles appear on the other blackboard. Sometimes the actresses speak to each other. Sometimes they repeat one another.

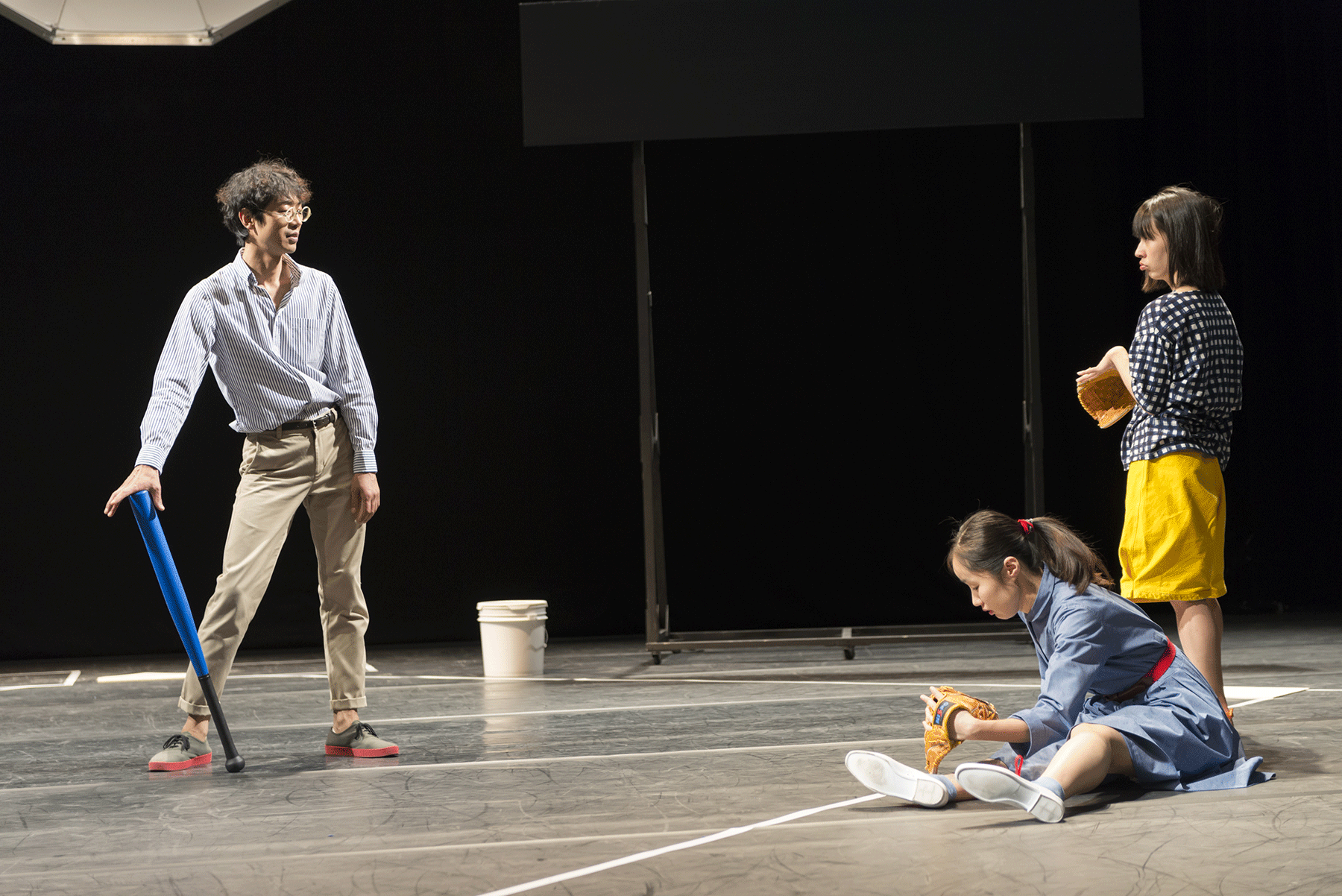

The actresses continue fidgeting before Korean actor Yoon Jae Lee joins them on stage. He attempts to answer their questions. The women ask him about innings and batting order, who throws, who catches, who runs where. They conclude that baseball is quite boring because if you are not batting or catching there is not much else to do. Exasperated, Lee admits he does not even like baseball that much himself. His father was a huge fan, reflexively making him dislike the sport.

Up to this point the pace of the play been relatively slow, but that changes once the character portrayed by Japanese actor Pijin Neji joins the conversation. His character is a man who posing as the renowned Japanese baseball player Ichiro Suzuki. Speaking in Japanese, Neji explains that to understand baseball you have to act it out. He offers insight into Ichiro’s techniques, showing his remarkably accurate Ichiro swings. This playing with the malleability of identity hints toward what will come later.

The faux-Ichiro explains that baseball is just an allegory for life; It all starts at home plate. The first goal is to do anything for that step away from home towards first base. Once there, one must make the right decisions to get to second base. More calculation of circumstances is required to get to third. But in the end, one always wants to return home. The ultimate goal is to return to that comfortable place called home — be it geographical, social, intellectual, or cultural.

Okada has written that he was very interested in the reception of the play by an American audience particularly because the piece critiques the United States’ cultural and political behavior abroad. As the birthplace of baseball, the US is an enormous cultural influence and presence. This reality is reflected in the presence of US military bases in Korea and Japan. In some way the countries are always in a competition for power under the shadow of the assertive US figure, fighting to remain the stronger baseball team. The website Japansociety.org describes the work as “positioning the U.S. as the parent and Japan and Korea as brothers.” This present-day game of power play is rooted in historical tension between these countries originating from the occupation of Korea by Imperial Japan.

In the play, the competitiveness of baseball is linked to the concept of identity. Rooting for the home team reflects the social divisions of regionalism and nationalism. But the rigidity of those identities are challenged near the play’s end.

After an exchange with the faux-Ichiro, Lee’s character explains how the Japanese town his father grew up in had a strong regional baseball team. Nozu interjects with a line clarifying the sudden confusion. She says, “Oh, you’re playing a Japanese character?” He says that he is. Nozu later divulges that she is playing a Korean character.

At some point, Wi’s character then gets caught up talking about Cracker Jacks. She divulges that in her culture there is a popular snack much like Cracker Jacks. But she is talking about the Korean culture, the native country of the actress and not her character. The actress breaks the fourth wall and announces she will go back to playing the Japanese character she’s been assigned to portray. The fluidity of the characters suggests an idea of the permeability of identity.

Much like a real baseball game, the play feels very long. Despite the strange ending, Okada presents a narrative that beautifully navigates the audience between politics of baseball, identity, and power.