In November of 2014, Cleveland police shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice for playing with a toy gun in a recreation area. A witness called 911 to report that “a guy” was waving and pointing a gun that was “probably fake” at passers by. The witness’ doubt about the gun was never relayed to the officers. Nor was the fact that the caller also said that Tamir was possibly a “juvenile.” It was only after Tamir’s death that the officers identified the weapon as a pellet gun with the orange safety cap scratched off. Officers Frank Garmback and Timothy Loehmann claimed that Tamir reached for the gun in his waistband when they arrived on the scene, and Loehmann opened fire.

After local and national pressure, the Cleveland police released the surveillance footage of the encounter to the public four days later. The footage revealed that the Loehmann shot Tamir before the officers had even stopped the car. Officer Loehmann quite literally jumped out of the moving car and fired within seconds of arriving on the scene. The video also shows that neither officer administered first aid. I, like millions of others, watched Tamir die on camera.

There have been a number of recent developments in the Rice case. Cleveland Prosecutor Timothy J. McGinty released enhanced security footage and a frame-by-frame analysis of the encounter. According to CBS News, “The analysis doesn’t appear to contain any new or substantive information and doesn’t clearly show whether Tamir, as police officials have maintained, was reaching into his waistband for the pellet gun when Loehmann shot him less than two seconds after getting out of the car.”

Officers Loehmann’s and Garmback’s statements were made available to the public for the first time December 1. In them, the officers double down on their initial claims, stating again that they believed Tamir to be a threat. Loehmann wrote in the report, “With his hands pulling the gun out and his elbow coming up, I knew it was a gun and it was coming out. I saw the weapon in his hands coming out of his waistband and the threat to my partner and myself was real and active.” A forensic expert hired by the Rice family claims Tamir wasn’t reaching for the toy at all as he wouldn’t have had time to do so given that the officer fired so quickly. It should be noted that no charges have yet been brought against the officers.

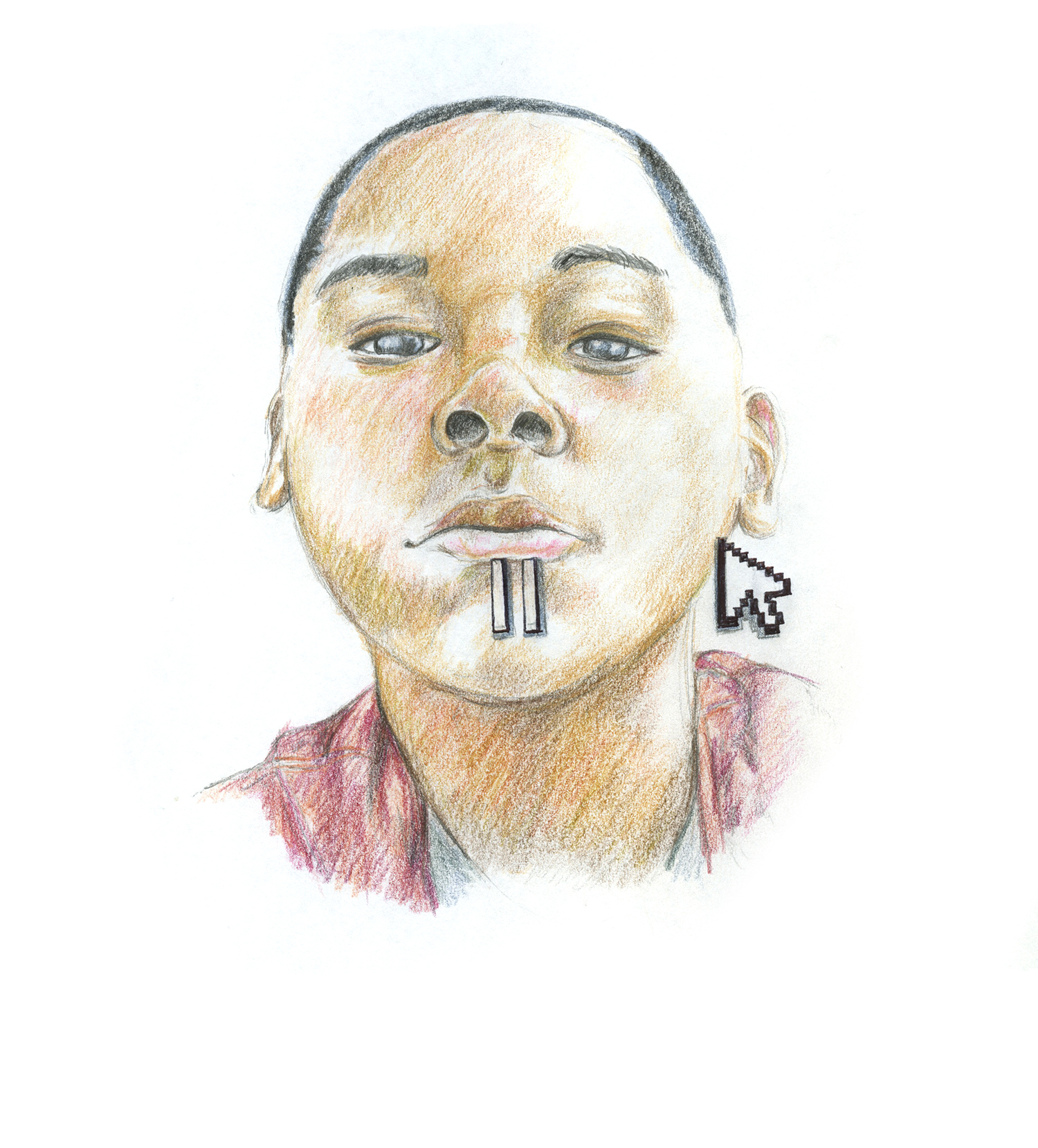

I remember distinctly what it was like to play with a toy gun. One Christmas, my parents bought my brother and me toy laser guns. They were gray with red lights that flashed whenever you fired, and you carried the toy by the shoulder strap. There was also a belt with a sensor that would make a high-pitched siren sound if you were hit by the other person’s laser. My younger brother and I hid in closets, ducked under the stairs, and ran in and out of bedrooms and bathrooms firing at each other until the pitch of the sirens grew increasingly flat and the batteries died that same day. We were astronauts, superheroes, villains, cops, robbers, allies, enemies, and sometimes all at the same time.

At 12, I still felt compelled to play, but there was a seriousness to it now — a sacredness. It became crucial that the rules of play matched the rules of the actual world. I remember asking for and receiving a toy shotgun. I went into the kitchen, found a black permanent marker, and colored the bright orange, plastic cap at the tip that marked it as a toy. The ink from the marker would fade, and I would return from outside to apply a fresh coat. I helped my brother do the same. My mother was horrified to see what we had done and made me wash off the guns with fingernail polish remover. She was afraid of us getting in trouble, I understood that. She didn’t seem to understand how important it was for them to look real. Play was serious work.

My mother was panicked seeing the toy I had rendered dangerously real. I scrubbed and scrubbed the safety cap of my gun until it was bright orange again. She understood the fragility of my young, black life in ways that I could not and perhaps still cannot.

I recognized from the Tamir Rice video the postures of adolescence. His pacing, playing with the toy, becoming bored with an idea, turning to a new one, slipping in and out of the seams of play. It confused me how he could have been read by the officers or bystanders as anything other than a child. Even the 911 caller had acknowledged it.

I watched the video because I am a part of a number of activist circles who argue passionately (and I believe rightly) for the value of watching videos like these in that they are important in seeking legal justice, speaking to the need for increased surveillance of police officers, and impressing upon the public the gravity of racialized police violence. It did none of those things for me in that moment. I had simply chosen to bear witness to something traumatic.

Mamie Till famously held an open casket funeral for her son Emmett who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955, and her actions are credited with launching the Civil Rights movement. Similarly, Tamir’s mother, Samaria Rice, has fought for the video to be released to the public and has become an advocate appearing in a number of television programs and interviews.

The power of Mamie Till’s decision was in part due to the rarity of the image. There was certainly a history of lynching photography, but it had been intended to be a site of celebration for whites and shame and terror for blacks. In rejecting the narrative of shame, Samaria draws from the lineage of Mamie and sees her son’s death as a call for social change. But in the age of the hyper dissemination of information and the saturation of images, what is the psychic toll of seeing an Emmett Till every week? The videos somehow manage to be both horrifying in what they reveal and mundane in their regularity.

I think often now of the strangeness of this ritual of watching brown and black people being brutalized and killed on camera. It is a profound strangeness; this practice of families requesting to watch the deaths of their loved ones, and then being pushed into decisions about the spread of those images.

I write now in the immediate aftermath of the release of the video of the killing of Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old who was shot 16 times by Chicago police, yet another child we have watched die on camera. It took approximately 400 days for the footage to be made public. There are even reports that police officers tampered with security footage in a nearby Burger King. Shyrell Johnson, the lawyer for Laquan McDonald’s family, said that Laquan’s relatives did not want the video released because they believed it would be “too painful for the family and community” to watch repeatedly.

I’ve written before about the desire in progressive and some activist discourses to frame these deaths as being in service of a larger movement, and how that push may prevent us from grieving individuals as individuals. To that point, what of the families like that of Laquan McDonald who wish to grieve privately, do not desire to become activists, and are retraumatized by the spread of those images? Legally, their anxieties do not trump the court ruling, and perhaps in the long run, their personal feelings are less important to the movement to end racialized police violence. However, what does it mean to grieve personally and intimately a loved one whose death goes viral?

In truth, these videos are often necessary in pursuing a legal outcome. They do not guarantee convictions or even charges (as is the case for Tamir Rice and Eric Garner), but white supremacy is so powerful that the absence of these videos almost certainly leads to the absence of justice. Since the release of the footage of Laquan McDonald’s killing, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has fired Police Chief Garry McCarthy and the head of the Independent Police Review Authority Scott Ando has resigned. The video only came to the public attention due to the actions of a whistleblower.

The national dialogue on race has shifted profoundly thanks in large part due to the efforts of groups like #blacklivesmatter. There has been a renaissance of activism on college campuses. The media is held accountable in racial discourses in ways that were not even possible just ten years ago. These are important gains and are undoubtedly linked to the mass spread of information made possible by social media and the prevalence of images of racial violence. The videos make the larger public aware of the daily realities for many black and brown people. And it’s fair to say that actually living with the fear of racialized police violence is likely more serious than the fear produced by watching that violence on camera. But might those images intensify that lived fear particularly for people of color?

As I mentioned before, the long-term good may outweigh the anxieties produced by watching the videos. However, what does it mean when a tool used to bring about liberation also causes trauma? My thoughts turn to this unacknowledged pain — this suffering deemed necessary — for people of color of who are constantly inundated with images of this racialized brutality as we struggle to build a more perfect union.