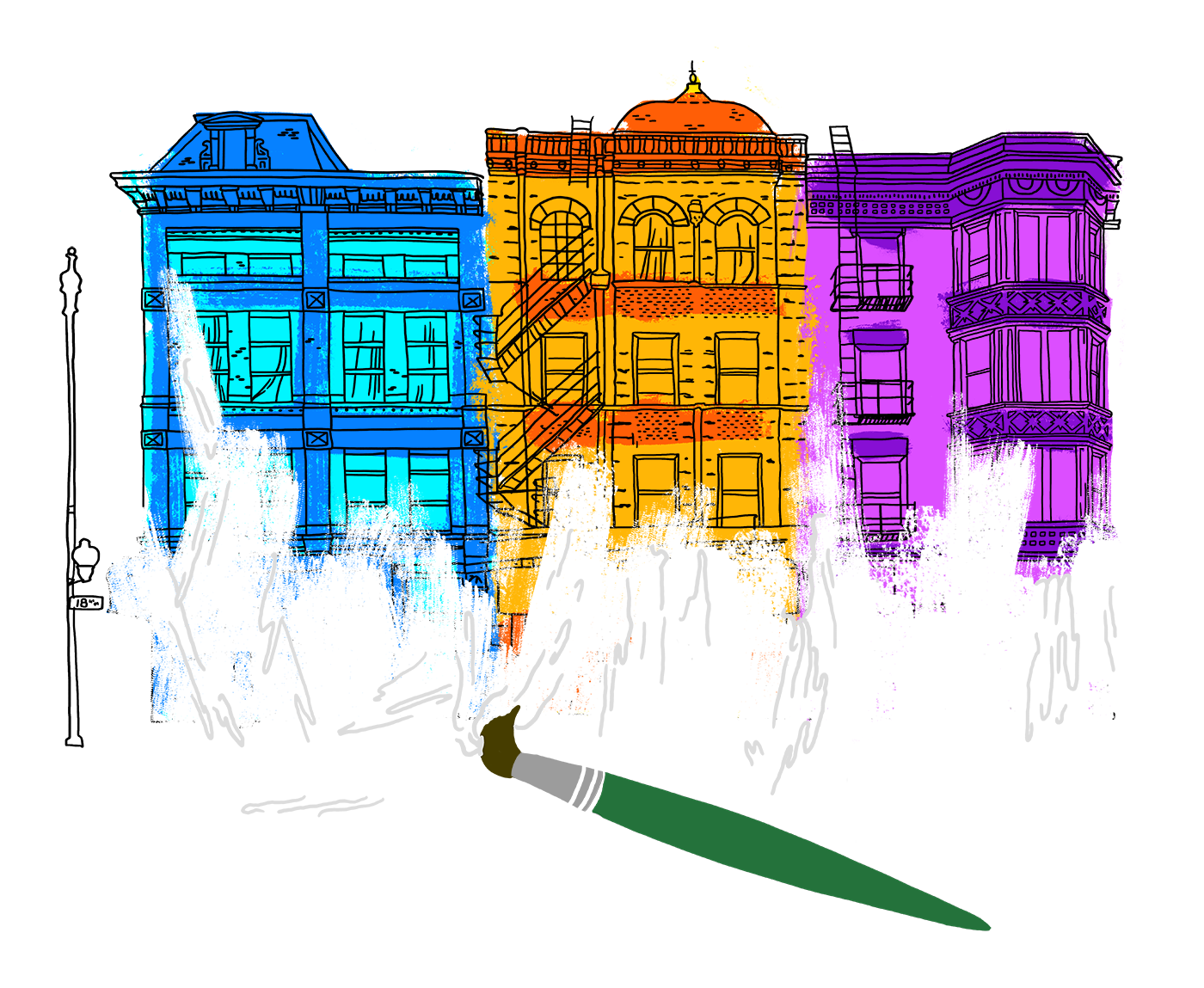

Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood is a place of extremes. The neighborhood’s principle artery, 18th street, greets residents with colorful murals of Aztec symbolism against sweet aromas of fresh baked bread. A few blocks north on 15th Street, a rusty freight train zooms by to carry shipments to the Loop. South of the pink line CTA stop is the coffee shop Bow Truss, whose minimal aesthetic welcomes hipster newcomers to the neighborhood. Beyond its charming exterior however, Pilsen is changing.

The steady encroachment of trendy coffee shops and contemporary artist venues has made it impossible to overlook the capitalist cycle that has targeted several working class neighborhoods across the nation: Gentrification. Gentrification, the gradual displacement of working class communities by median income groups, is a looming reality to Pilsen residents. Though the neighborhood has been gentrifying for the past 11 years, the transformation of spaces into upper middle class cultural meccas is making it increasingly difficult for long-time residents to stay.

Pilsen’s hybridity has served as a source of inspiration for School of the Art Institute (SAIC) artist and professor Amanda Gutierrez from Mexico City. Gutierrez said, “In my second year of graduate school at SAIC, all of my work was related to immigration and the Mexican diaspora here in Chicago. What my work tries to emphasize, though, is that it’s not only Mexicans in Pilsen who have experienced this type of displacement. We have to understand Pilsen as a neighborhood made by migrants. At first, it was inhabited by people from the Czech Republic, and then Mexican migrants that arrived to Chicago in the 1950’s.This fusion between two migrant cultures within one space, is what fascinates me.”

Gutierrez uses documentary film to tackle the cultural erasure that can occur when gentrification targets a community. She lead a walk as part of her project Out Of The Map: Critical Itinerary of Displacements, that departed from High Concept Laboratories in Pilsen. She had the opportunity to screen her 2005 documentary “En Memoria,” where she additionally provided live reenactments of some of the interviews featured in the film.

“One of the main characteristics of this documentary is that you don’t see talking heads expressing ideas, you only see voice overs and the empty spaces that people live in. This is because displaying a person’s face often induces audience members to render an identity, and in this case, I’m trying to highlight the way in which the race identity in gentrification can be very problematic,” Gutierrez said.

Gutierrez believes that neutralizing the identities of participants allows viewers to look more complexly at the issue of race, which in her opinion, is a feature of the capitalist system. According to Gutierrez, it is used as a strategy to brew antagonisms amongst community members.

Gutierrez is from Mexico City and says, “Even though I’m Mexican, it doesn’t mean that I’m not part of the problem or the phenomenon. After talking to several people from alternate perspectives, I understand that it’s a problem more so about class, than race,” she said.

An artist community like SAIC can unknowingly contribute to the process of gentrification because of this often-unspoken element of social class. Gutierrez said, “Art institutions play an important role in gentrification in Pilsen, not because they want to be gentrifiers, but because art is one of the most common commodities in the real estate market uses to attract attention to a neighborhood. They’re looking for something that’s fashionable and hip.”

Gutierrez’s art practice brings attention to the ways in which artists can be used as vehicles to advance a political agenda. As artists and art enthusiasts, we must be aware of our function within a system larger than ourselves.

“Artists are used as the scapegoats to rehab a place culturally, aesthetically — we essentially become a capital tool. Sadly if you have good marketing, you can make a Mexican mural a really enticing advertisement for the neighborhood. Which is what what’s happening right now. In the end, we start bringing attention to a genre of art and culture that don’t speak to the original community who was already there,” she said.

So how do we help end this cycle? Gutierrez underscores the importance of awareness. “We should be aware that our culture is being used and exploited without us even noticing. This means we can either impose our own artistic universe within a gentrifying space, or we can contribute to it and share our talent with others. And with my knowledge and art practice, I invite people to share ideas together,” she said.