Cybertwee’s New Form of Feminist Artist Collective

The ♡♡ cybertwee ♡♡ Facebook group hosts an infinite scroll of member-sourced posts conjuring digital sincerity, softness, and sweetness. Any visit to the page yields images such as those of hands modeling fake nails made from circuit boards, women sporting 3D-printed dresses with sparkle-emblazoned sneakers, pastel-toned pixelated landscapes, faux-fur smartphone cases, or a dildo carved completely out of rose quartz.

The group is also on the front line of an evolving discussion on what Rhizome Artistic Director Michael Connor describes in a February 2015 editorial as a “defense of Internet saccharine.” Cybertwee, according to founder Gabriella Hileman and co-founders May Waver and Violet Forest, is “a crowd-sourced visual and sonic vocabulary, an aesthetic, genre, brand, ideology, and way of life.” The artists’ webpage adds another layer to the definition: “If cyberpunk had a cute kid sister that was secretly better at coding.”

Literally, “cyber” refers to computers and technology, while “twee” is British slang for “excessively sweet,” and by extension, the Twee DIY music movement of the late 1980s and 1990s that emphasized tenderness in response to punk aggression. In its ideological role, Cybertwee draws deeply from cyberfeminism — which proposes networked technologies as spheres free from societal and gender constructs — in order to infuse intimacy into open-source communities.

Hileman, a Chicago-based new media artist whose practice centers on the body and identity as expressed in cyberspace, was an undergraduate student in Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) when she realized she had encountered very few women writing cyberpunk and science fiction, an issue that informed her thesis project.

“I wanted to look closer at the role that women play in those kinds of fictions as well as in the construction of identities online through text or avatars,” she explains. As part of her research, she started the ♡♡ cybertwee ♡♡ Facebook group with the intent to observe how femininity is expressed in online spaces.

On Facebook, Hileman met Waver, a Wisconsin-based artist who focuses on technology’s role in relationships, and Forest, a graduate student in Art and Technology Studies at SAIC (and F Newsmagazine’s Webmaster) who creates web browser-based work.

“A lot of my friendships have been initiated on Facebook,” Forest says. “I basically grew up online and not always talking to people face-to-face.”

The three soon found that they shared a number of interests, and all envisioned cyberspace as a place to foster sincere interactions. They decided to collaborate under the Cybertwee collective, using the Facebook page as their first platform.

“Facebook feels more like a community than other social media platforms, especially with the idea of mutual friendship,” Waver notes. “Instead of ‘following’ someone, you enter into a mutual visibility; they see what you’re doing and you see what they’re doing.”

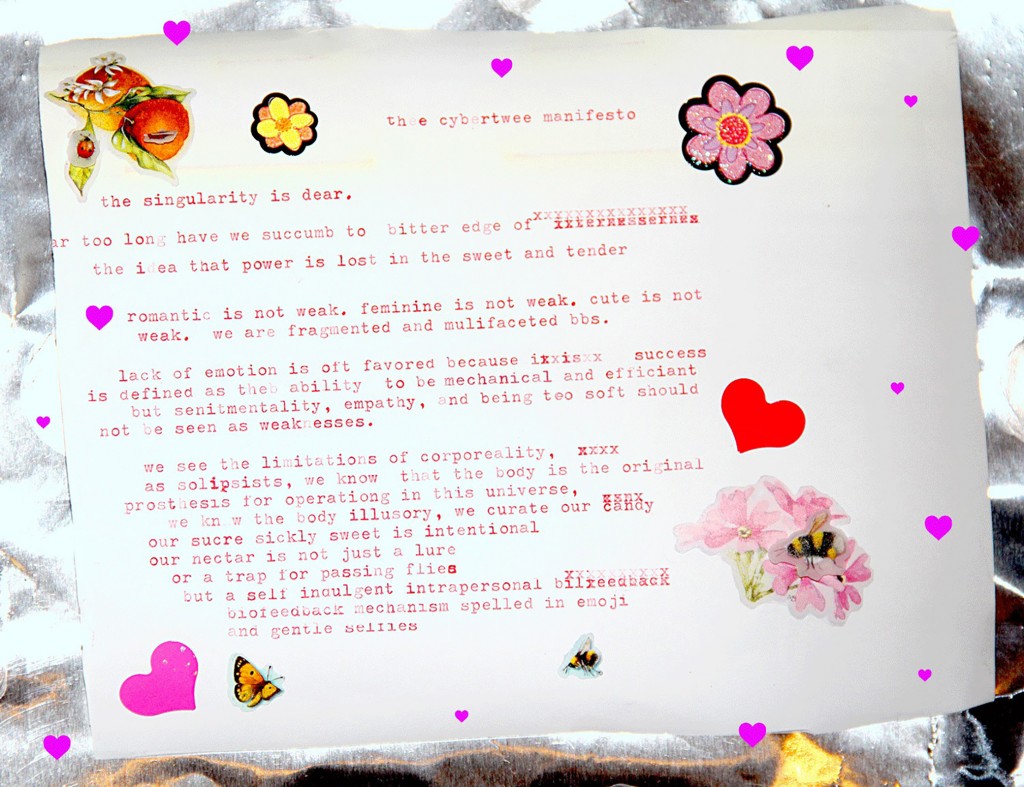

Hileman, Waver and Forest decided to meet in real life in Chicago in fall 2014 to talk about Cybertwee’s potential. “Violet had the idea that we should write a manifesto, so we had a slumber party and drank wine and had cookies and M&Ms,” Hileman explains. “We set a typewriter out in the middle of the floor and started talking about our ideas.”

The result was the cybertwee manifesto, a document beginning with “the singularity is dear,” a utopian twist on computer scientist Ray Kurzweil’s famous theory that “the singularity is near,” or that society is approaching a point where technology will surpass human comprehension. It asserts that cuteness is far from weakness: “we are fragmented and multifaceted bbs.”

The group cites futurist and post-human works, including scientific feminist scholar Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto and Australian artist collective VNS Matrix’s A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century (both published in 1991), as deeply influential.

“Microcultures tend to be fleeting, so to put ideas down into a solid form helps capture an essence of an attitude of a time,” Hileman says. “It’s a risky thing to do, since writing a manifesto calls for contradiction. Manifestos are set up to fail.”

“It’s a strong statement, but it’s also a great way to start conversation and bring awareness,” Waver adds.

Much of that conversation has stemmed from the Facebook group, which currently includes 678 members. The three administer the group and actively contribute content, but otherwise allow members to post freely. Their intent is to create a safe, supportive digital space for people of all genders and disciplines to discuss and critique artistic and feminist issues.

“There’s the bravado and aggression of male-dominated spaces and discourses, and at the same time there is pressure on women to be super resilient and outspoken,” Waver says. “I don’t think that my liberation looks like that of a man’s. It looks more like the context of Cybertwee in embracing vulnerability and emotional complexity.”

“It’s really important to us that we embrace being feminine, and that it’s ok to do so while being feminist,” Hileman says.

Cybertwee has therefore evolved a framework to address the ongoing discrimination that women working within technology industries and communities face. In a recent project, Forest critiqued the hyper-masculine culture of case modding — the practice of modifying a computer case in order to improve its performance — by retrofitting a computer inside of a Barbie Dream House. “Why is it that women don’t want to be part of that world?” she asks. “Is it innate that we don’t want to be hands-on with technology, or is it really our choice to feel that way?”

This echoes in some of the commentary that the three artists receive about their physical appearances, in addition to their work. While the majority of feedback is overwhelmingly supportive, there have been a handful of unwelcome reactions. Shortly after Rhizome published a review of Waver’s work this past winter, one man wrote the group a long message outlining in detail how he thought they could “do better,” discrediting Cybertwee’s basic tenets and encouraging them not to overlook distance and toughness in cyberspace.

“To say that it was mansplaining is kind of harsh, but that does feel accurate.” Hileman says. “It was like he was patting us all on the head.”

While Cybertwee aims to be all-inclusive, some members of both the online community and the Chicago art world have expressed intimidation or describe a “clique-like” specificity and perceived exclusivity to Cybertwee’s visions of feminism and femininity. Others have mentioned that cuteness tends to be a characteristic that is more empowering from a male standpoint, rather than a female one.

Science fiction narratives offer safe spaces to forge origin stories and new identities, and Hileman, Waver and Forest perpetuate Cybertwee as an intentionally open set of ideas ripe for re-appropriation. “The Facebook group is crowdsourced, so there’s so many different ways that people can interpret it, or come to it feeling like their life already involves Cybertwee in some way,” Forest says.

Artist-curated archives of images proclaiming new aesthetics have skyrocketed in tandem with the rise of social media, and in this sense Cybertwee is not alone. “There are other kinds of cultures that are rising up in this same vein as us, and that’s why this ideology has resonated with so many people,” Hileman says. “There definitely was a hole in the Internet where this kind of femininity was missing. We are trying to bridge that, to patch it up.”

Cybertwee is rooted in its online iterations, but it extends into the physical world to unite under the banner of art. The three artists hosted a party with a number of DJ sets at a Chicago club in February, and more recently participated in an exhibition curated by new media artist Molly Soda at SXSW, and they have collaborated with multimedia publishing platform Newhive. Now, they are entertaining the possibility of curating a group show with crowdsourced submissions of visual and written work, in conjunction with a panel or discussion event.

In line with the historical trajectories of other futurist art movements, Cybertwee will eventually iterate what it will look like to live in a post-Cybertwee world. But for now, boundaries are fluid, all linked by computer screens as canvases.

Jessica Barrett Sattell is a Chicago-based design and technology journalist. She is more cryptopunk than cyberpunk and definitely cyberfeminist.