The Speed of Sound at the Farnborough Wind Tunnel

In 1935, when the Q121 24 foot wind tunnel was built, it was the largest return-style aerodynamic testing tunnel in Europe. It remains so today. This July the tunnel was opened after over two decades, and for the first time to a general public. Instead of aerodynamic research, the unique and now Grade 1 listed architectural site in Farnborough, about an hour outside of London, hosted concerts of experimental sound.

The Wind Tunnel Project, under the umbrella of the Artliner organization has planned a program of film screenings, artist talks, concerts and installations. The events take place within both the large cement Q121 wind tunnel that was used for whole airplanes and full-scale fuselage, engines and wings as well as the R52 smaller wooden tunnel, with the smoothest possible wind-flow, used to test meticulously crafted scale models.

Thor McIntyre Burnie’s “The Speakers” is installed in the Q121 until the end of July and plays when there are not concerts. The artist has composed a soundscape of choral chants and nightingale song interrupted with 1942 recordings of overhead Lancaster bombers. James Bridle’s Drone Shadows is also installed throughout the month, an outline of the shadows cast in fast-flying satellite photography of drones taken from above, spying on the spies.

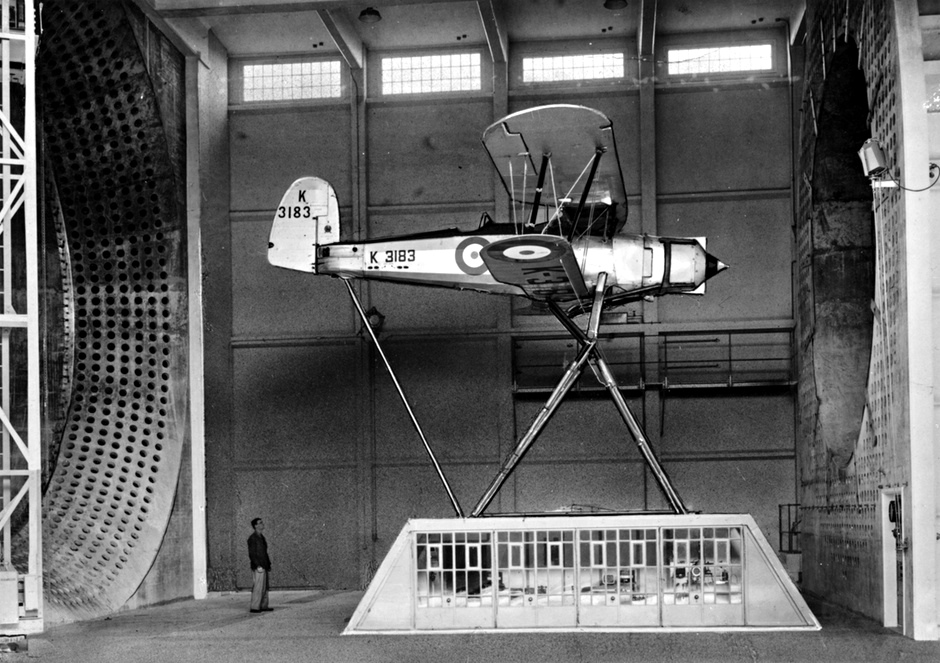

On July 6th, students in the MA History of Design program at the Royal College of Art (RCA) curated the “Speed of Sound”. Graham Rood a former aero-acoustics researcher at the wind tunnels began the evening with a talk on the history of testing on the site, sharing images of bending trees pinned by the roots, tilted road signs, stationary jaguars with engines running, and entire aircraft suspended between the 24 foot diameter laminated wooden fan and the tunnel opening opposite, the very place where the audience sat. He explained that the noise created by aircraft is due to a disruption of the laminar flow of air over the wings, causing interaction between the pressure waves of air. This is felt as turbulence and heard as noise below.

The Factory on this site produced airships from 1912, and warplanes for WWI from 1914. Renamed the Royal Aircraft Establishment at the end of WWI, the Factory continued to turn out SE5a fighter jets by the thousands. In 1991 it was renamed yet again as the Defense Research Agency, and has been known as the Defence Evaluation and Research Agency since 1995. A top-secret research facility, the Farnborough area still contains working hypersonic wind tunnels where Schlieren photography captures images of shockwaves from scale-models blasted with increased density air flowing at 9 times the speed of sound. The essential fact to grasp about a wind tunnel is that instead of the plane moving through the air, the plane is still and the air is what moves.

The history of military interaction with sound continued with a talk by Boo Wallin, a recent RCA graduate who shared his Sound as Terror project that investigated the soundscapes in areas with regular drone activity. Interestingly, Graham Rood shared with me later on that enrollment in the Empire Test Pilots School, formerly on the Farnborough site has decreased due to increasing reliance on unmanned aircraft. Boo’s talk concluded with a performance within the space of the wind tunnels. Recordings of drones from onsite journalists in Waziristan and Gaza were played on speakers throughout the reverberant concrete chambers of the Q121. The audience drifted through the eerie signal, that amplified through the concrete became requiem sung by a mournful choir of concrete pillars.

Tall cement blades put in place to smooth the flow of air divided the area into chambers. The audience could squeeze between the scooped lamellae, and listen to the sounds in a side filled with light between the blades of the fan, or in complete darkness at the other end of the tunnel. The only light was filtered through the tall slits of the cement blades.

We also heard works by Aki Pasoulas and Paul Fretwell who had brought the panoramic Genelec sound-system from the University of Kent. Their compositions exploited the range and subtlety of the speakers and spatial acoustics with manipulated recordings of Gamelan and tales from London’s Kings Cross area.

The highlight of the evening was the transcendental synth duo, Teleplasmiste (artists Mark Pilkington and Michael J York aka Strange Attractor), who attempted to create standing waves and activate the space through resonant frequencies. Before they began playing they told us that they were planning on using the resonant frequency of the eyeball, 19HZ, and we should let them know if we had any resulting hallucinations. The pair were avowed fans of achaeoacoustic research that has linked ancient sites, such as Newgrange to sonically induced trance states. Standing in the gaps of the cement columns and singing along with the tones of the synths produced a beautiful beating effect. A chorus of singers made up of inquisitive audience members added a layer of spontaneously ritualistic song. The evening continued with performances by CindyTalk and Dalhous, electronic musicians with an aesthetic of wide dynamics and pulsing rhythms.

The audience, suspended throughout the tunnels experienced the effects of pressure waves rolling over them, but amplified and modulating rather than perfectly smooth. If you have the chance to go, take the train and get to Farnborough for this uniquely placed venue with a charged historical resonance.