James Turrell Illuminates The Possibilities of Perceiving The Infinite

Entering Darkness Matters (2011) feels like entering a tomb, or perhaps a haunted house. After signing a waiver at the door, the security guard informs me that I have ten minutes inside the chamber. She shows a map of the space, which diagrams the bent corridors, and where the chairs would ultimately be. Upon entering, the only guide is the sense of touch along the metal handrail and felted walls. The industrial materials for public use and safety contrast with the unknown potential of the limitless darkness. I inch through slowly, sitting down and looking out into nothing. I blink and the darkness outside and behind my eyelids is the same. Finally, after about five minutes of swiveling my head around the room, I notice a faint russet glow, hovering on the back wall. I feel like I might be looking at the back of my own eyeball. I blink and close my eyes. The memory of the hazy cloud lingers on my retina and once again my eyes, open or closed, reveal the same image. This is the breadth of the vision, a very faint distant glow, which is unreachable, and might not even exist. The similarities between the work and the mysterious stuff of unknown physical properties that makes up the majority of our universe is striking. Like dark matter, or more accurately dark energy, Darkness Matters is visible through its effect rather than its substance. I hear the footsteps of the guard up the ramp, and she calls out, “Your time in the exhibition is up.” It’s been ten minutes. A maximum of two are allowed inside, but I am unaccompanied. I feel my way down the ramp and enter the daylight of the gallery preparing for the next phenomenological adventure. The didactic informs that the glow was a dimly lit incandescent bulb.

Light Reignfall (2011), a light program within the Perceptual Cell series, is another work that activates the apparatuses of perception, including the potential of solitude. Two attendants in white lab coats hand me another contract that I sign to say that I am prepared for the psychedelic effects. I choose the “hard” program rather than the “soft,” as one attendant, who has experienced both many times over her months of work, informs me that this option is more likely to create an out of body experience. After removing my shoes, I lay down on a white leather bed and am handed noise cancelling headphones and a panic button on a string to wear around my neck. Entering the work is slightly spooky, as if I am being interred in a mausoleum. Once inside the steel dome, a former gasworks storage chamber, the light is a pure sky blue, projecting softly onto a limitless dome. Droning sine tones begin to sound in the headphones. The pitches shift, creating binaural beats, which are meant to entrain neurological electric pulses and induce meditative states. A pure red, and then darkness, intersperses with the blue. Wherever I can turn my head, there is always a spot in the center of my vision, the shadow of my cornea. The speed of flashing increases until I no longer see separate envelopes of color, but rather pulsing geometric forms that slither flickeringly in a space of infinite depth. At one point, a tear flowed down my cheek and I had no idea whether my eyes were open or closed.

Contemporary Culture, Moscow

James Turrell is adept at offering viewers the experience of containing the infinite within their own physical perceptions, which is simultaneously expansive, revelatory, and occasionally terrifying. James Turrell: A Retrospective, at LACMA from May 2013 – April 2014, is the artist’s first retrospective since 1985. The exhibition is part of a nationwide drive for recognition which began last spring with simultaneous, albeit shorter, shows at the Guggenheim in New York City, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The shows will perhaps draw financial support for Turrell’s unfinished natural observatory, Roden Crater. The LACMA show is the most wide ranging of the three, including sketches, aquatints and early projection light works. Afrum (1966) is the first installation, a white light projected onto a corner conveying a solid floating cube. In another room, a number of holograms show three dimensional planes of color, with a few incorporating projections as well. A whole gallery is dedicated to Turrell’s far-flung “sky spaces,” which use projected light on an aperture facing the sky to, as Turrel puts it, “bring the space of the sky down to the plane of ceiling.” An additional gallery space shows models and images of his unfinished opus of the last 35 years, the natural observatory Roden Crater, that conveys the “vastness of the cosmos within the tangible space of human experience.” Some of the installation works at LACMA have recommended viewing times to allow for adjusting eyes, like Key Lime (1994), a “wedge-work” that transforms the dimensions of the room through thin angled frames of beamed light. Timed tickets ensure that visitors have an experience of their own perception without a crowd, and feel comfortable lingering.

Turrell has worked at LACMA before, as part of their burgeoning Art and Technology program. In the late ’60s he collaborated with artist Robert Irwin and aerospace psychologist Ed Wortz, who led the Garrett AiResearch corporation lab, testing environmental control systems for NASA’s manned space flights. A foundational experience for the trio’s research was individually spending up to eight hours inside a dark anechoic chamber at UCLA. The withdrawal of sensory information heightened the perception of the sensory apparatuses themselves. The trio experimented with meditation, and audio entrainment, and went on to create a “Ganz Field,” saturating one’s vision with 360 degrees of pure white light.

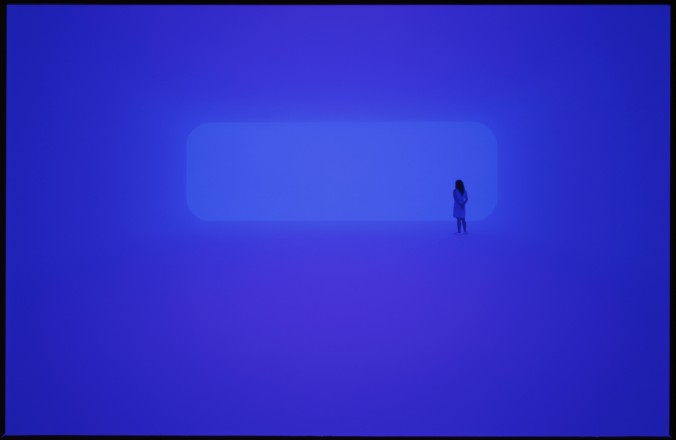

Breathing Light (2013) is part of Turrell’s Ganzfeld — meaning “complete field” — series and was commissioned for the show. After waiting in a queue, seven people are allowed to enter the antechamber of the light space. The guard gleefully guarantees that this is the highlight of the show and we’ll be able to see our toothpaste, perhaps differentiating brands by the glow of our fluoride smiles. We’re given booties, and watch as the previous group descends the tiered steps before walking into what initially appears to be a suspended blue screen. The curved white walls of the space lead to a luminous glow that slowly shifts, flooding the ovate tunnel with color. Turning around, the entrance appears as a screen again, shifting from turquoise blue to deep forest green because of the surrounding frequencies of luminescence.

Speaking of his own work, Turrell has suggested that his medium is perception, because “with no object, no image and no focus, what [else] are you looking at?” A master of neon, argon, ultraviolet, fluorescent and LED, he brings the immaterial within our reach.