Exploring Collaborative Artistic Communities in Chicago and Beyond

Speaking from personal experience, the most difficult part of relocating to a new city has been the loss of an established creative community. I find myself longing for the support and opportunity enabled by collaboration. It seemed to happen so organically, but before I relocated to Chicago for grad school I had a fortunate, even unusual situation. I was embedded in a quaint city with concentrated levels of creativity, and I resided in a building at the nexus of this activity owned by the artist known as Mike Bonanno, leading member of highly collaborative activist duo The Yes Men.

As I seek to rebuild a similar supportive network, I have spent a lot of time contemplating the nature of collaboration. It can take shape in many ways. In the simplest of terms, collaboration is a tool to achieve something beyond what one is able to accomplish individually. It could also be said that in partnerships there is strength. Working in a group can offer a sense of empowerment because there is less individual risk. Also, each individual brings a different skill set to a group dynamic, enhancing the possibilities for discovery and outcome. Last but not least, collaboration can occur between already established relationships, nurturing a close bond that enables new creative potential.

In an academic environment where creative people are brought together for short periods of time, what level of collaboration is really possible? I interviewed a variety of people involved in successful collaboration in order to better understand this question. I begin with the most familiar.

The Yes Men harness creativity as a tool to affect social, political, and environmental reform around the world. They have even inspired positive change right here in Chicago, with an action carried out in collaboration with Columbia College students that that helped close the Fisk Coal power plant in Pilsen last year.

While the success of The Yes Men relies on highly organized collaborative effort, what is of particular interest is the trajectory of their growth. What began as a partnership between two artists grew to include many friends, then an army of volunteers, to the present when The Yes Men receive thousands of inquiries from people interested in participating worldwide. They have inspired an urge to collaborate that requires an enormous amount of organization and resources. When I caught up with Bonnano, he emphasized The Yes Men’s current effort to make the monumental task of connecting artists and activists sustainable.

Through December 31, The Yes Men are focusing on a fundraising effort (you can help by donating at yeslab.org/supportus). The donations will help support an online platform they are developing called the Action Switchboard. “It will be kind of like match.com for creative activism,” said Bonnano. The goal is to create a sustainable way to help host activity for social change. And while it is inspiring that The Yes Men have built such a large demand for participation, the effort is only as strong as the support structure behind it. When asked if fundraising could be considered a form of collaboration, Bonnano answered yes: “I think of the executive producer of a film, that person gets a major credit line for participation in the form of dollars. Without that support, the film doesn’t happen.”

It is not a new idea for artists to rely on a larger group for structural support. For another model I looked to the HATCH program at the Chicago Artists Coalition, a staple in the arts community in the city. The HATCH program, a yearlong residency pairing curators with artists, began when Cortney Lederer, Director of Exhibitions and Community Initiatives, questioned how the space, which had been supporting Chicago artists for years, could also support curators.

When asked about how the residency fulfills the idea of collaboration, Lederer emphasized the community building aspect. HATCH participants, both artists and curators, come together regularly not only in the studio, but also informally for potluck meals and group critiques. These casual conversations strengthen the program, but are also intended to build a lasting alliance among the network of participating artists and curators. Lederer noted: “what we hope emerges from these very intentional relationships is a healthy and supportive creative community, that together, can excel in unique ways within a profession that can often be very isolating.”

Lederer’s program goals are inspiring. The emphasis put on individual achievement in the arts can indeed be isolating, even fostering a dangerous prison-of-the-self mentality. The weight put on the individual can be lessened when striking a balance between singularity and social connectedness.

For further understanding of the value of participation I looked to Canadian artist Micah Lexier, who recently visited SAIC and will return next Spring term as a Visiting Interdisciplinary Graduate Advisor. His work is largely dependent on collaboration. In projects like 1,334 Words for 1,334 Students Lexier relied on hundreds of participants. This type of project, however, fits more the category of an organized effort according to Lexier, who instead finds direct interpersonal exchange to be significant to his practice.

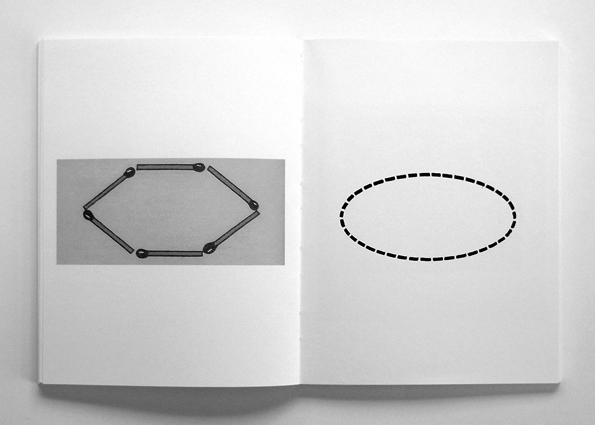

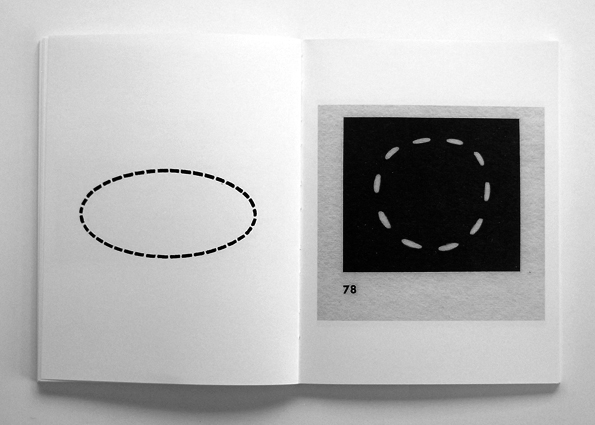

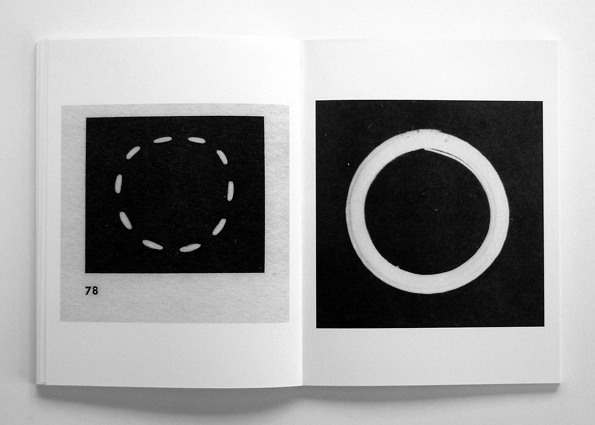

For the book project Call Ampersand Response Lexier engaged in a call and response exchange of images between himself and a friend. He noted that this wordless dialogue is one of his most meaningful collaborations. “I got to work with an artist I deeply respect, and there is an element of play and playfulness that I thoroughly enjoy…I have a feeling that this project could last for years or even decades if we are lucky. I don’t want it to ever stop.” Lexier values this close interpersonal exchange as a way of nurturing his creativity, promoting communication that is so seamless neither person can identify where an idea first began.

Now, returning to my my original question, I wonder how an institutional setting can enable lasting connections. While in theory there is a built-in creative network provided by the School of the Art Institute, how are working relationships compromised in a competitive environment? After much consideration, it seems critical to recognize the merit of collaboration not only as a tool for creative accomplishment, but also as a way of reaching meaningful goals that are larger than the self. I encourage all members of campus to be thinking of how they can actively collaborate.