The Art and Legacy of José Guadalupe Posada

This year’s 27th annual Day of the Dead Celebration at the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) is enriched with an exhibition marking the 100th anniversary of the death of José Guadalupe Posada.

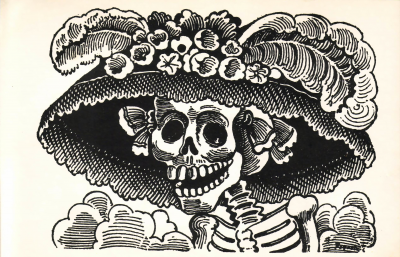

You might not be familiar with Posada’s name, but you have undoubtedly come across his work before. The cartoonist and illustrator’s most iconic contribution to the arts in Mexico is La Catrina (The Fancy Lady), a smiling skeleton face wearing a European hat adorned with flowers and feathers. La Catrina is central to the Day of the Dead celebrations’ imagery and it is the common theme of the NMMA exhibition: 100 años de Posada y su Catrina (100 Years of Posada and Catrina).

Extending beyond printmaking and engraving, the exhibition brings together a wide range of media testifying to Posada’s artistic legacy in the past 100 years. Curator Dolores Mercado also wished to highlight the connection between Posada’s work and the Day of the Dead by incorporating altars made specifically for the exhibition by Mexican artists she carefully selected during her research in the printmaker’s hometown. Even though the artists selected for the show are all Mexican (residing in Mexico or in the US), Posada’s imprint has effectively spread across all borders.

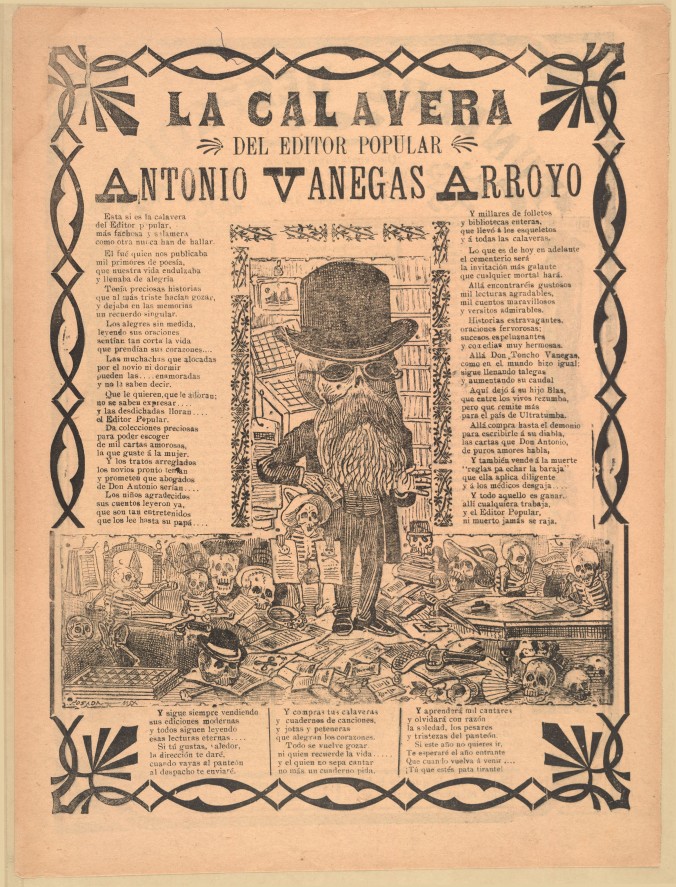

His career as a printmaker developed between 1876 and 1913, coinciding with the dictatorial presidency of Porfirio Diaz. Despite the political repression suffered under Diaz, Mexico profited from significant technological progresses including significant technological innovations in printing processes. These allowed for a street literature to develop under the form of pamphlets, broadsides and large format journals.

Posada’s most acknowledged illustrations were featured in broadsides relating crime stories, scandals, and local curiosities, with a satirical tone. Their emphasis on illustrations and their accessible price made these broadsides popular within the working class.

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for his prints, Posada was impoverished and almost completely forgotten by the end of his life. After he died, no one claimed his body, which was thrown into a common grave.

It took a decade for his work to be rediscovered by French-born painter Jean Charlot who participated in the birth of Mexican muralism. The muralists adopted Posada’s illustrations as a benchmark for their movement, as they believed it epitomized Mexican cultural identity. Being at once popular and socially engaged, Posada’s work was a perfect expression of the post-revolutionary trends in Mexican artistic practice.

La Catrina in particular became part of the popular mythology, and appeared in murals alongside prominent political and social Mexican figures. As curator Dolores Mercado explained to me, Diego Rivera completely revived Posada’s creation by giving La Catrina a full body in his mural Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central) in 1946.

Artists of varying backgrounds have been influenced by Posada and have had their work serve his creation of La Catrina. Pedro Linares, a papier-mâché artist, was one of them. His life-size Catrina, which he created and put together with his family in 1974 greets visitors at the entrance of the exhibition. Pedro Linares’ family has been bridging the gap between popular art and high art in Mexico since the 1930’s, when he first created the Alebrijes, amazing papier-mâché creatures, which are now an integral part of the Mexican cultural imagination. His son, Miguel Linares, also works wonders with papier-mâché and three of his sculptures are shown in the exhibition. The first one is a giant Zapatista Skeleton (1989), and the other two, both created in 1993, are smaller representations of Frida Kahlo and Rodolfo Morales as skeletons.

The paintings of the tattoo artist Pedro Diamante for the NMMA exhibition is an example of Posada’s La Catrina presence in modern aesthetics and alternative art forms. Tattoos portraying stylized Catrinas, and imagery of young women with faces painted like Day of the Dead sugar skulls have exploded in popularity in the last few years. Artists outside of Mexico have also been greatly influenced by Posada’s creations. This is especially evident in the work of the San Francisco born graphic artist Sylvia Ji, who, in exhibitions like “La Catrina” (2012), often represents women as Calaveras.

Beyond La Catrina, Posada’s preferred artistic medium of printmaking and engraving has remained popular in the contemporary Mexican art world. Self Help Graphics is a non-profit art centre located in Los Angeles and focusing on making fine arts printmaking accessible to the Latino community since 1970. In Oaxaca, Mexico, the Takeda Biennal dedicated to all forms of printmaking has been up and running since 2008. The town of Oaxaca itself counts over fifty printmaking workshops and is home to the Institute of Graphic Arts (IAGO) where the largest collection of prints in the whole of Latin America is kept.

Posada’s legacy is threefold: in addition to his aesthetic and his art form, his intentions have also lived on. The socio-political resonance of Posada’s work and the relationship between printmaking and satire in Mexico remains relevant. As part of its exhibition, the NMMA presents the audience with three highly satirical prints from anonymous artists of the Assembly of Revolutionary Artists (ASARO) illustrating the 2005 popular uprisings in Oaxaca. At the time, the Popular Assembly to the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) occupied the city for six months, protesting against the authoritarian politics of the governor of Oaxaca. ASARO supported these protests creating several works including woodblock prints, linographs and lithographs.

Posada’s work, his Catrina print, and the imagery related to the Day of the Dead celebration are an obvious source of inspiration for both Mexican and foreign artists, but this great popularity of his puts them at risk of being appropriated for commercial purposes and put into forms of extreme commodification.

Posada’s work is not copyrighted and consequently, many of his original Calaveras (skeletons) and Catrinas can be found on tee-shirts, notebooks, stickers, cups, and even underwear. Worse, the designation “Day of the Dead” was almost trademarked by Disney last May in an attempt to facilitate merchandising sales that were to follow the release of an animated film in partnership with Pixar, focusing on the Mexican celebration. The furious disapproval of the Mexican community in the US, supported by American artists, led Disney to withdraw its trademark application.

The appropriation of both Posada’s and the Day of the Dead’s imagery by audiences and creators outside Mexico will have had at least one positive outcome: reconciling Mexico with its traditional roots. As Dolores Mercado explained to me, the Day of the Dead celebrations were falling into abeyance, as the younger generations preferred to celebrate Halloween and people tended to live too far away from their ancestors burial place to take part in the celebrations. However, seeing the international enthusiasm for the Day of the Dead, it seems that Mexico is growing back into it, and the history of the celebration is once again taught in primary schools.

The exhibition 100 Años de Posada is on display at NMMA until the 15th of December. It is an opportunity to see myriad of interpretations of Posada’s Catrina by both popular and fine art artists, a visual feast for the Day of the Dead.

Great Article.