“Never let the memorial be the end, because the struggle is not over with. Until we bring to justice those who prosecuted, those they had question marks about whether or not they were guilty, whether or not they had been tortured – until we do that, I wouldn’t give a flying dove if you put a memorial on every corner.”

— Darrell Cannon, torture survivor

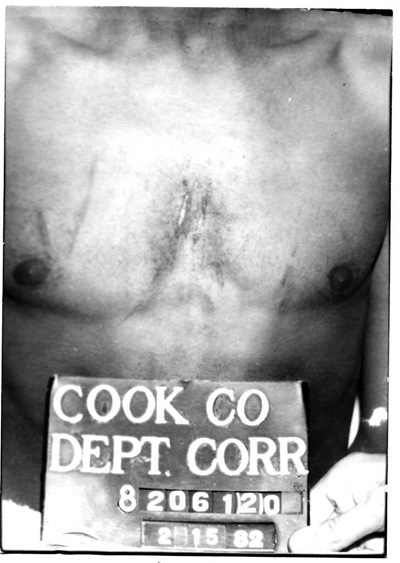

“I only had a couple bruises on my arm and a busted lip. But the rest of the injuries were internal from the electricity shot through me with the black box,” Anthony Holmes testified during the two-day sentencing of Jon Burge. “I still have nightmares, not as bad as they were, but I still have them. I wake up in a cold sweat. I still fear that I am going back to jail for this again. I see myself falling in a deep hole and no one helping me to get out.”

Forty years after the first allegations of police torture, the specter of Burge continues to loom over the city of Chicago. On January 21, 2011, the disgraced former Chicago Police Commander was sentenced to four and a half years in federal prison for obstruction of justice and perjury. This small measure of justice pales in light of the testimonies of decade-long police torture.

From 1972 to 1991, Burge and detectives of Area 2 tortured over 195 black men from the South Side of Chicago until they confessed. In a brick building on the corner of 91st and Cottage Grove, the alleged criminals were interrogated, beaten, burned, suffocated and electroshocked.

Chicago’s dark history of police brutality and corruption has long been shrouded in silence. A determined group of activists, journalists and lawyers has condemned the willful blindness of the city and the state of Illinois. Former Cook County state’s attorney and later mayor Richard M. Daley currently faces conspiracy allegations in a lawsuit filed by Michael Tillman for ignoring abuse complaints filed against the police and aiding in the cover-up.

Holmes, a former leader of the Black Gangster Disciples, remembers the police torture of May 30, 1973: “I remember looking around the room at the other officers. I thought one of them would say that enough was enough. They never did.”

The police force and the city refuse to admit responsibility or apologize for the torture.

“What you see before you today is a very bitter man,” confessed Darrell Cannon at a roundtable discussion of torture survivors. In 1983, after a forced confession, Cannon was convicted of murder and incarcerated for 24 years before he was exonerated and released. “I keep hatred within me. I would never in life tell you that I could forgive. As long as I’ve got breath in my body, I will never forgive.”

In the mahogany dining room of the Jane Addams Hull House, a group of artists, activists and educators gathered. The March 17 Open House was the continuation of a series of grassroots charrettes and roundtable discussions to generate ideas for memorials of the Chicago torture cases.

“We don’t have any illusions that a torture memorial can heal these wounds,” explains SAIC professor in the Film, Video and New Media Department Mary Patten. “The struggle is how do you incorporate this traumatic event that happened to you, make meaning of it and go on.”

Chicago Torture Justice Memorial (CTJM) is calling for proposals from artists and justice seekers for a yearlong series of exhibitions beginning in late June. The project is to extend throughout the city of Chicago from the South Side Community Art Center, to Westside Chicago Public libraries, the downtown Sullivan Center, and Mess Hall in Rogers Park. Conceived of as an educational grassroots project, the goal of CTJM is not the erection of a monument, but through performances, roundtable discussions, lectures and exhibitions, to stimulate dialogue in the public sphere concerning the Chicago torture cases.

“The proposals will allow individuals to take the events into their own consciousness and create their own relationship to them,” says SAIC sculpture professor A. Laurie Palmer. “The open call will allow a critical mass of people to engage with the issues in ways they might not otherwise engage by simply hearing news broadcasts.”

Conflict over official and unofficial histories – whose voice should be heard and whose suppressed – complicates the tradition of the monument. For decades, testimonies of the torture victims were ignored; it was a black man’s word against a white man’s, a convicted criminal’s against a cop’s. “It often seemed there were two cultures in conflict in the courtroom,” reports journalist John Conroy in a 1990 Chicago Reader article “House of Screams.” “One was black, poor, given to violence, and often in trouble with the law. The other was white, respectable, given to violence, and in charge of enforcing the law.”

“The memorial form is problematic,” argues Patten, “especially if it is attempting to speak for a unified voice, arrive at a consensus and close the chapter on these awful events.”

“Never let the memorial be the end, because the struggle is not over with.” Cannon’s voice intensified with each statement as he addressed the audience gathered at the torture survivor’s roundtable. “Until we can bring to justice all those that prosecuted, those they had questions marks about whether or not they were guilty, whether or not they had been tortured, until we get Daley to show that he’s not the Teflon Don – until we do that, I wouldn’t give a flying dove if you put a memorial on every corner. A memorial is just a figure. Let the memorial be a starting point for us to say, ‘We will never tolerate this again. We will never again turn a blind eye.’ ”

CTJM organizers insist that the voice of the black community should no longer be ignored as it was throughout the history of the torture cases. The open call does not announce a competition and there will be no jury. Each voice will be heard and each submitted proposal exhibited.

SAIC photography professor Daniel Bauer is skeptical whether a purely grassroots initiative will raise the desired awareness. He argues for a high profile juried architecture competition that would call for proposals for a municipal monument. He remains adamant: “The memorial cannot be anecdotal.” With the support of donors, foundations and the press, the competition could open a nationally publicized conversation. This approach would be more likely to put pressure on the city to confront its misdeeds.

CTJM is part of a continuing effort to obtain justice for the torture survivors. Chicago lawyer and partner at the Peoples Law Office Joey Mogul hopes a reinvigorated public interest in the torture cases will exert pressure on the City Council to support a reparations ordinance. Reparations could include financial compensation, psychological treatment and vocational training for the victims.

The trauma of police torture has left a black scar on the city of Chicago. It is difficult to conceive of a memorial while torture victims remain in prison without hearings, Area 2 officers have yet to be prosecuted for their crimes and the city refuses to take collective responsibility.

“What we can do is act in solidarity with the survivors,” declares Palmer. “If you feel like you have to be a survivor to do or feel something about torture, it is a huge loss of an understanding of what it means to be part of a community.”