Sharon Hayes is the epitome of what formalist and conservative aesthetes hate about contemporary art. Her work is queer, political and feminist but these aren’t the only reasons to love her.

Hayes also addresses the complexity of communication depending on the temporal and social context in which it is located. She asks questions such as how many voices can be heard at one time before the result becomes noise? Every utterance from a long gone companion may be impossible to forget. Alternately, we may not hear a single word from a Republican primary debate broadcast and re-broadcast through a 24-hour news cycle. Voice carries varying weight depending on who is speaking and why, as well as who is listening. We may have never listened to Rush Limbaugh, but we have certainly heard him lately.

Hayes’ first solo museum exhibition in the US at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) closed on March 11. It addressed not only the convergence of public and private speech, but also the potential of communication wrapped in various forms of political affect. Hayes, a mid-career artist based in New York, was featured at AIC as a part of the contemporary art focus series.

The exhibition was comprised of three parts, the video installation “Parole,” seven digital chromogenic prints of spoken word record covers arranged thematically titled “An Ear to the Sounds of Our History,” and finally, “In the Near Future,” a room of slide projections.

“Parole” circulated thematically connected videos around four screens of varying size that were embedded in an enclosure constructed from plywood and soundproofing foam. The fabricated space acted primarily as a symbolic barrier from the rest of the gallery. Included in the installation were diverse forms of speech – from a lecture and discussion by University of Chicago professor Lauren Berlant, a speech by James Baldwin, a letter to a friend, to some of the artist’s public performances.

In many of the videos, performer and artist Becca Blackwell travels through various public and private spaces – a kitchen, recording room, public squares and outdoor shopping malls (which are now often the same thing) – recording, listening, justifying viewership through example, yet rarely reacting to the events and speeches that are occurring. Her presence is formal, offering continuity, but also representing a model of contact. She never speaks but she is not inactive.

The seven digital chromogenic prints of spoken word record covers that make up “An Ear to the Sound of Our History” were individually organized to suggest sentences comprised of the album titles. Along with their semantic suggestions they provide miniature aesthetic historical snapshots. They are the visual equivalent of the DJ set performed by Hayes in which she remixed her collection of spoken word albums.

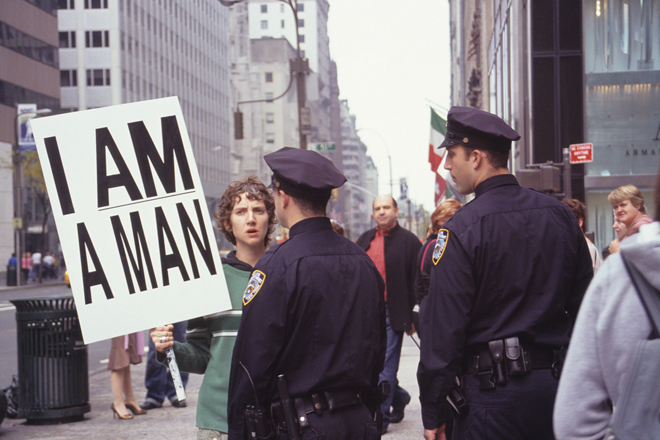

The final room of the exhibition contained “In the Near Future” a collection of projected images from Hayes’ protest sign performances that occurred between 2005 and 2009. In each projected image Hayes stands alone holding an emblematic protest sign. It becomes obvious quite quickly, however, that many of the slogans don’t function in the orthodox timely and persuasive style of political street language. Some of the signs address the Vietnam War while others are declarations such as “I am a man.” In this way the signs represent public address divorced from the urgency and the impotence of timely political speech.

In one section of “Parole,” the voice of author James Baldwin considers the role and motivation of a writer. He notes that there comes a time when “a writer realizes he is involved in a language that he has to change.” In the discussion with theorist Lauren Berlant, Berlant locates optimism in habitual acts of someone whose place in the world has been annulled. The example Berlant uses is the businessman who, after the financial collapse, would wake up every morning, put on his suit, take his suitcases and leave his home with nowhere to go. In the context of these statements “Parole” and the exhibition overall operates as a poetics of breakdown and hope in political language.