Of

Sound

Mind

SAIC investigates student mental health and what can be done to prevent an escalation of mental health related issues

Anxiety Disorders

Mood Disorders

Other Disorders

Health

Behaviors

The Healthy Minds Study (HMS) is an annual, national survey that examines mental health issues among college students. It is a partnership between the University of Michigan School of Public Health, the multidisciplinary University of Michigan Comprehensive Depression Center, and the Center for Student Studies in Ann Arbor, MI. Since its launch as a pilot study, 50 schools including SAIC have participated in HMS’s three data collections.

Anyone who is suicidal may receive immediate help by logging onto suicide.org or by calling 1-800-SUICIDE. Suicide is preventable, and if you are feeling suicidal, seek help immediately.

Infographic by Patrick Jenkins

“To say ‘I need to see someone because something is wrong with my mind’ is scary. But then again, it’s also the use of the term ‘wrong with’ that causes these problems too. No one wants to be at a disadvantage and no one wants to know that there’s something wrong with the way they process the world,” said Jessica Mazza, a leader of the Active Minds student group at SAIC.

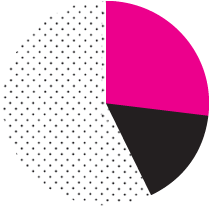

Mazza’s statement illustrates one of the many possible reasons why the majority of students in need of mental health care do not ask for help. According to the 2009 Healthy Minds Study conducted at SAIC, only 41 percent of students who screened positive for depression or anxiety disorders sought treatment of any kind in the past year. This number is especially concerning because, in concordance with the troubled artist myth, artists have much higher rates of mental disorders. The SAIC student body has numbers between two and five times higher than the national rates of mental health issues.

The SAIC community is aware of disorders that exist within school walls, though many view their prevalence as less of an epidemic and more of a lifestyle. “I think that we romanticize artists as troubled types,” says Peter Kusek, a student pursuing an MFA in Film, Video and New Media and an MA in Art History. Kusek’s sentiments echo a stereotype that has been prevalent in mainstream society ever since artists like Vincent van Gogh and Arshile Gorky rose to prominence after tumultuous lives and gave way to similarly troubled modern figures like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. “In our art school culture, there’s still a value to being dysfunctional,” says Kusek, “and in general, our culture gives extreme allowances to people who are seen as ‘talented.’”

But even Kusek identifies mental illness as “an edge that enhances productivity and makes work more personal.” Adding that “there’s also a general fear that if you don’t have it, you won’t be able to make what you make.”

This mindset is indicative of the lack of a typical stigma associated with disorders at SAIC. Less students think of their moods as being “abnormal” which could possibly be stunting the number of students who seek treatment. Alex Rowland, a fourth-year BFA student in the Visual Communication Department, thinks of art school as the kind of place where artists are allowed to flourish regardless of their psychological state. “I don’t feel like it’s a social issue [at SAIC],” he says. “Art schools lend themselves more to these types of mental disorders – it’s a more emotional environment where you’re always venting feelings.” Rowland is also quick to identify that the peers and colleagues he shares creative space with are like-minded with respect to the kind of emotional release that art-making affords. “[Expression] is helpful because we’re also letting it out in a beneficial setting,” he says.

Kusek feels similarly about the cathartic properties of art-making. “Art is therapeutic,” he says, “and the people that are drawn to making it are often trying to remedy something.”

Raising Awareness

“At the Wellness Center what we are trying to do is make sure we are identifying students at risk early and intervene with them earlier, developing integrative care services,” says Joseph Behen, Executive Director of Counseling, Health, and Disability Services at the school. Recently SAIC was awarded the Garrett Lee Smith Campus Suicide Prevention Grant, which consists of a three-year grant of $306,000, a sum which was matched by SAIC. Part of the strategy to prevent fatal consequences of mental disorders is the exchange of information between physical and mental health services. “Our health services regiment includes screening for depression, alcohol abuse, etc., with help from nurse practitioners, and if students screen positive, we let them know about care options,” says Behen.

Among the projects the school will develop with the grant money is a third Healthy Minds Study two years from now, which will refresh data. The Mental Health First aid training on campus will also be expanded – around 100 staff members have already been trained and the Wellness Center expects to cover the majority of the staff, as well as interested faculty and student leaders. There are also plans for the implementation of web-based self-aid programs that will offer help to students with depression by giving simple instructions and recommendations for wellness and health.

Related to the grant is the Student Resource Room in the Wellness Center with light therapy for Seasonal Affective Disorder, where a health promotion specialist is present eight hours a week. Also planned are suicide prevention workshops called “Making Connections,” a program that started at Columbia College when they received the same grant in 2005.

Thinking back to the results of the study conducted in 2009 and taking place again currently, it is inevitable to ask why artists seem so much more prone to these problems when compared to the rest of the population. The prevalence of bipolar disorder at SAIC, is five times higher than the national sample of college students (5% to 1%), and the same ratio is true of the category of “any substance abuse” though Behen says there might be more than a few overlapping cases.

Mental health at SAIC compared with national averages

Finances, Time Use, and Attitudes

their current situation

is a financial struggle

that completing degree

will be worth time, cost,

and effort in a scale of

in paid job hrs

about job prospects after

finishing education

Suicidality

in the last year

1% to 2% Students who seriously

thought about suicide last year

Daniel Grant, author of several books about artists’ lifestyles considers the challenge of attending art school particularly stressful compared to other forms of education. In an article for the Chronicle of Higher Education, he says that artists “may receive a certain level of technical training – how to draw the human figure, how to cast bronze, how to render a design on the computer – but they are expected to produce something that is original almost from their first class.”

“[Artists] have to be creative on demand,” says Patricia Farrell, director of the counseling center at the Maryland Institute College of Art. “They then have to handle a public critique,” she explains.

According to Grant’s article, “many of the therapists and psychologists working in art colleges’ counseling centers tend to have a connection with art.” Some of them seem to be very aware of the relation between mental issues and creative practices. Martha Cedarholm, a nurse practitioner and director of the Pratt Institute’s counseling center, says in the article that her staff is attentive to the problems of “treating depression or Attention Deficit Disorder, without flattening students so that they lose some of their creativity.”

At times SAIC has embraced some of these problems by celebrating the work created by artists who experience mood disorders. “Touched by Fire,” which started in Toronto, made its way to Chicago, where SAIC entered 45 submissions by students with mental disorders, of which 10 were selected and exhibited. The project has an annual juried show in November, as well as an online virtual gallery.

For Behen, trying to determine the causes behind the high rates of mental disorders among art students might amount to nothing but speculation. Nevertheless, he thinks that “it goes with the territory of being in an art school that makes work on the cutting edge and whose students perhaps live their lives in such a way.” On the other hand, this is by no means a state to be seen as permanent. Emilie Smith, Mental Health Promotion and Care Specialist at SAIC (who was hired as part of the grant) explains: “If someone has depression it doesn’t mean that they came out of the womb that way and they are going to die that way – that is not who they are as a person. Things shift and change. People get help and improve. So it isn’t like those are the only students we have and that’s what it’s going to always be. It’s important to know that the work that we and the counselors do helps and changes things.”

The American College Health Association’s 2009 National College Health Assessment said that 19 percent of all U.S. college students report some kind of mental disorder. So the problem goes far beyond art schools. Colleges nationwide are aware of this and are already working together to fight these problems by sharing information and seeking common solutions.

Why are artists are so much

more prone to these problems

when compared to the rest of

the population?

The prevalence of bipolar disorder

is five times higher than the national

sample, and the same ratio is true

of the category of “any substance

abuse disorder.”

The National College Depression Partnership (NCDP) is a group of universities and university counseling centers that have identified the need to work together to better address mental health issues among their students. “We have a need to do a better job to detect students in distress before they harm themselves, and then secondly, once we detect them, to engage them in care as soon as possible. We would then use the latest evidence-based approaches to care so that we can maximize the student’s ability to return to academic function,” explains Henry Chung, the project’s director and former Associate Vice-president of Student Health in New York University on the NCDP website. SAIC is a member of this partnership.

“We have also developed an extraordinary relationship with faculty over the years,” said Felice Dublon, Vice President and Dean of Student Affairs. “This year in particular, the Faculty Senate, under the leadership of Patrick Rivers, has shown a commitment to working with the Wellness Center in identifying how they, and in turn, their faculty colleagues, can reach out to students in need with information about the many resources available at SAIC.” Dublon also goes on to voice her approval of the school’s recent efforts, commending Behen, his staff, Student Affairs and all other involved parties for “having some of the best resources for all students exploring their mental health.”

Treating mental disorders is extremely expensive and time consuming, and given the high rates at our school, the challenge becomes more complicated. For staff, SAIC has three psychologists and one postdoctoral fellow in psychology, besides four students from local doctoral programs training through part-time externships and Behen himself who is a clinical psychologist. According to Behen, in terms of student-to-counselor ratio, we compare favorably to other schools, but what SAIC is able to offer is assessment and 16 sessions of brief psychotherapy. It does not offer psychiatric care – students in need of such treatment are referred to outside treatment centers.

Unlike SAIC, two of the largest independent art colleges in the United States, the Pratt Institute (4,800 students) and the Savannah College of Art and Design (9,000 students), both have full-time psychiatrists or psychiatric nurses who can write prescriptions.

Finding Help

When asked about the source of psychological disorders in art students, many members of the SAIC community acknowledge the issue, but hesitate to see it as a deep-seated problem or epidemic. “I don’t know if there’s an outright cause that brings out these sorts of mental disorders – it could be genetic, or a change in one’s personal life or something school-related – but it’s also good to be critical of diagnoses in general,” says Jon Satrom.

As an instructor in the FVNMA department, Satrom has a first-hand perspective on the types of expression that beget passionate artworks. He is compassionate towards those who find adversity in their lives, but also states the difficulty of pinning down a disorder as such: “Overdiagnosis is a problem in our culture. I’m not against medicine or treatment, but one can ask: Is art school a Mecca for weirdos? Yes. It’s a unique place that attracts folks who see the world differently. Some might need clinical treatment, some may find consolation in their art, and some may simply operate at a different frequency.”

Nick Foster, an SAIC student, was diagnosed with Bipolar 10 years ago and echoes Satrom’s sentiment about “overdiagnosis.”

“I am leery of psychiatry and its neat (and often arbitrary) diagnoses and what it considers pathological and ‘disordered,’” says Foster. “That’s not to say pathology doesn’t exist. … [I] have suffered through debilitating depressions, delusional manias, drug overdoses, shock treatments, and multiple arrests and hospitalizations. According to current western psychiatric practice, someone with this history would need to be medicated so that he or she could maintain ‘stability.’ Though I am not advocating this for everyone, I take no medicine and have been ‘stable’ for more than four years.”

Foster also goes on to state his independence from substance use/abuse, saying, “I don’t get high or drink anymore. … I ride my bike and do my work. I don’t view myself as disordered.”

Still, a history of trauma cannot be taken lightly in any setting. “When I first started college, I was doing a lot of cocaine and ecstasy, which coupled with my temperament and resulted in acute psychosis,” Foster continues. “I had a total psychic break. I had to drop out of school. … I had a couple of nearly successful suicide attempts.”

The issue of suicide at SAIC is one that the Wellness Center does not take lightly. The results of the 2009 Healthy Minds Study showed that 10% of SAIC students had suicidal thoughts in the previous year (compared to the national average of 7%). According to Joseph Behen, SAIC has gone seven or eight years since the death of an enrolled student by suicide. Behen attributes this particular low number to “the significant efforts we make through Counseling Services, Health Services, the Disability and Learning Resource Center, Residence Life and Academic Advising to provide students struggling with significant personal distress with a strong safety net.”

Behen goes on to state that SAIC’s interest in pursuing the SAMSHA Campus Suicide Prevention Grant was “motivated not only by our interest in continuing to prevent suicide among SAIC students, but also to reduce suicidal behavior, self-destructive behavior and other adverse effects of unaddressed student distress.”

As for Nick Foster, the events in his life eventually led him to “decide to live,” which he adamantly states “was [his] choice and [his] alone.” The self-empowerment that Foster witnessed in his own life ultimately imparted a disbelief in the potential for a “grand solution,” in his words: “There is no bureaucratic solution, as much as this administration wishes there was.” Foster’s belief is that students should help each other in promoting good mental health, stating, “I would suggest that people look after one another. … It’s not complicated – if you see someone suffering talk to them.”

Wellness Center

116 South Michigan Ave., 13th floor

Hours: Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

Phone: 312.499-4288

Fax: 312.499-4290

Email: [email protected]