“Who I am is much more complicated than one absolute cultural identification,” says Theaster Gates, who often finds himself pushing against expectations and preconceived notions collectors and arts administrators have of his artwork and himself.

A student of urban planning, ceramics and, most recently, the legality governing non-profits, Gates certainly cannot be satisfied with any one identity. Similarly, his multi-faceted Grand Crossing space, the Dorchester Projects, exists as an enigma by traditional arts organization standards.

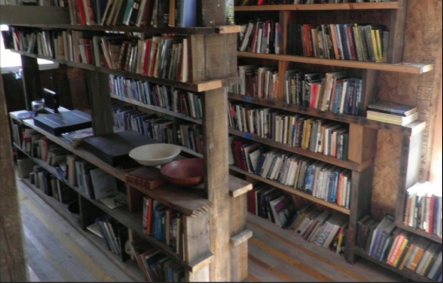

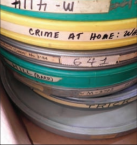

The Dorchester Projects are a series of houses on Chicago’s South Side on the corner of Dorchester Avenue and 69th Street. Some of the houses have been renovated to hold Gates’ archives, comprised of propaganda films of the 1950s and 1960s, thousands of glass lantern slides salvaged from the University of Chicago, art and architecture books from the closed Prairie Avenue Bookshop and thousands of records from the Dr. Wax Record Store. It is also Gates’ private residence, where he keeps a community garden. Over the summer, musician David Boykin used one of the homes as a studio to complete an album, and DJ/music archivist Ayana Contreras, using the LP archive, hosted dance parties at one of the homes on weekends. A movie theater, a dining hall – the iterations of identity in the physical place continue to evolve and grow.

One aspect of this new project is teasing out identities: personal, communitarian and institutional. Personally, Gates engages racial identity through his artistic practice as well as by serving his hyperlocalized, majority-black Grand Crossing neighborhood. Gates says that as a young child he was more conscious of his family’s Christian identity than of his black identity. As he worked with his father repairing neighbors’ roofs, he was more aware of being a laborer than of any racial distinction. It was not until his arrival at a predominately white middle school that he was able to recognize his own blackness. In his words, “My nose was wider and my hair was greasy.” It was this confrontation with otherness that allowed Gates to understand that black heritage and Christian heritage were only two of his plausible identities.

One aspect of this new project is teasing out identities: personal, communitarian and institutional. Personally, Gates engages racial identity through his artistic practice as well as by serving his hyperlocalized, majority-black Grand Crossing neighborhood. Gates says that as a young child he was more conscious of his family’s Christian identity than of his black identity. As he worked with his father repairing neighbors’ roofs, he was more aware of being a laborer than of any racial distinction. It was not until his arrival at a predominately white middle school that he was able to recognize his own blackness. In his words, “My nose was wider and my hair was greasy.” It was this confrontation with otherness that allowed Gates to understand that black heritage and Christian heritage were only two of his plausible identities.

In terms of community identity, the South Side is very particular. When we first came to Chicago exactly a year ago, we knew little to nothing about neighborhood profiles, but were well aware that Chicago’s South Side was presumably dangerous and that we should not go there. Few communities have as prominent a national profile (good or bad) as the neighborhoods that surround Dorchester Avenue, and that profile is exclusively black. Gates, however, says our view of the community should be more transparent. “People say this is an all-black neighborhood, but in fact a lot of the merchant activity that happens in this neighborhood happens by non-blacks all operating under the broad generic sphere of a ‘black neighborhood.’”

From an institutional perspective, the Dorchester Projects look like a community non-profit arts center, but in reality are a privately funded art project. To be sure, the Dorchester Projects do have a mission. But as Gates says, “I think as an artist I have the liberty to not have the burden of a mission. My mission could, in fact, change three months from now. The use of this house could shift.” The space avoids terms and classifications, preferring instead to exist as an incubator as much as an enigma. To label, monetize or mainstream the project would kill the creative spirit that exists there. “Conviction is way more compelling than an organizational mission statement,” Gates explains.

Racial identity is a complicated topic, especially in the art world. This was Gates’ sentiment about his own identity and the identity of the Chicago South Side community where Dorchester Projects is situated. Theaster Gates’ artistic practice has certainly grown in recognition and scope, but the Dorchester Projects represents his most ambitious effort yet. As he puts it, “if this house has been a certain thing to my neighbors, can my neighbors roll with me to accept that this house might change into something else? Have I been intentional in helping them understand that I am not a service agency or a not-for-profit?” Like Gates’ artwork, the Dorchester Projects are an artistic expression that changes and develops meaning through the process of creation.

Racial identity is a complicated topic, especially in the art world. This was Gates’ sentiment about his own identity and the identity of the Chicago South Side community where Dorchester Projects is situated. Theaster Gates’ artistic practice has certainly grown in recognition and scope, but the Dorchester Projects represents his most ambitious effort yet. As he puts it, “if this house has been a certain thing to my neighbors, can my neighbors roll with me to accept that this house might change into something else? Have I been intentional in helping them understand that I am not a service agency or a not-for-profit?” Like Gates’ artwork, the Dorchester Projects are an artistic expression that changes and develops meaning through the process of creation.