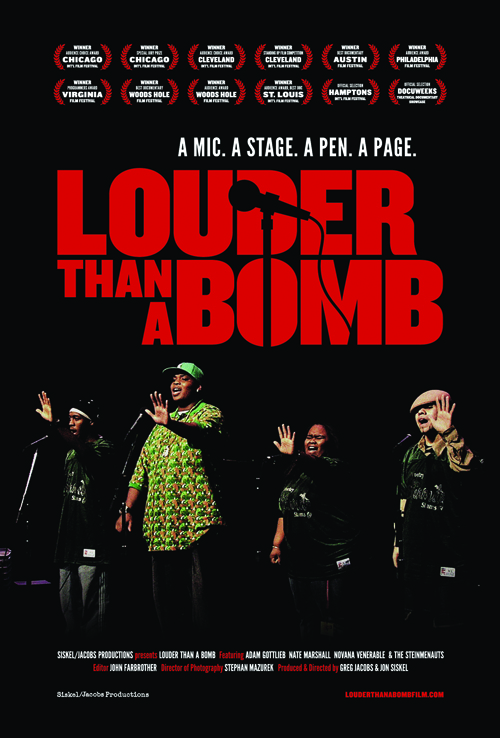

Chicago’s largest youth slam poetry festival hits the big screen

By Amanda Aldinger, School News Editor

“The point is not the points, the point is the poetry.” At other youth-based competitions the meaningless clichés don’t change the fact that it’s really all about winning. But at Chicago’s Louder Than A Bomb slam poetry festival, community is genuine and poetry is performed to win. It seems that maybe, just maybe, the point actually is the poetry.

Louder Than A Bomb (LTAB) is the largest youth poetry slam competition in the country. Conceptualized in 2001 by a group of Chicago school teachers and writers, the goal was to repair a growing dissonance in Chicago’s youth community. Kevin Coval — LTAB co-founder, local poet, and SAIC professor — and his fellow educators were struck by the disconnect between youth from different areas of the city, a situation worsened by Chicago’s radical segregation. He notes that around this time, “the city council was trying to pass the anti-gang loitering law that was also criminalizing young people of color in this city.”

Realizing that they were the missing link between their students, the educators began meeting once a month, sharing curricula and a desire to unite Chicago’s youth. “In that culture of fear we wanted to create a culture of hope,” Coval explained to F Newsmagazine. “So LTAB was a good, proactive solution to bringing young people together who had a lot to say and who were traditionally criminalized.”

[nggallery id=17]LTAB developed into a thriving annual event, providing youth from all around the city with the opportunity to compete with original poetry, and commune with kids they perhaps wouldn’t have met otherwise.

“The culture that has emerged from the festival is not just the festival, it’s not just the slam. You see a growing mass of young people who are ignited in their own education process and literacy in a way that I don’t think has happened before,” says Coval. Although the festival blossomed in its own community, it was still a local phenomenon until documentarians Greg Jacobs and Jon Siskel came along.

“It started just by accident, like so many of these things do,” Jacobs (co-founder of Chicago-based film company, Siskel/Jacobs Productions) told F Newsmagazine.

“I was driving down Clark Street with my wife in March of 2005, and we happened to drive by the Metro and there was a sign on the marquee that said something like ‘Louder Than A Bomb: High School Poetry Slam Finals Tonight,’ and there was a line of kids of all shapes and sizes and colors stretching down the block. To think that they were going to be onstage reading their own poetry, which I never would have done as a high school student — that also seemed really interesting.”

Jacobs’s partner Jon Siskel (the nephew of late film critic Gene Siskel) didn’t initially share his enthusiasm. “To be totally honest, I had seen a little bit of slam poetry, so I was a little reluctant,” he admitted. Nevertheless, Siskel was willing to go out on a limb. The two decided to meet with Coval, which evolved into the pursuit of turning Louder Than A Bomb into the filmmakers’ first full-length feature documentary.

At this point, 30-40 teams were entered in the competition (entry rates have exploded since the release of the film, with a staggering 600 kids registered for this year’s festival), but obviously, the documentary couldn’t chronicle each of their stories. So after traveling to schools and meeting with kids from all over the city, Jacobs and Siskel narrowed their focus down to four main stories culled from participants in LTAB’s 2008 festival: three individuals, and one team.

When reflecting on the stories the film tells, the word “inspiring” feels weak. There’s Nova Venerable, a young woman from Oak Park/River Forest High School who performs a poem she wrote entitled, “Cody,” about her younger brother diagnosed with a failed X chromosome, autism and diabetes. “Will he remember how he slept in my bed every night after Momma left/And I held him like an extra pillow, opened my arms with his restraints/When Daddy said to put him in the middle without a seatbelt, so he would be the first to die in car accidents/Can he know how he found a mother in big sister?”

Beyond her journey as a poet, the film follows her personal life as a devoted sister and daughter, abandoned by her father at a young age, a co-parent with her single mother. “She silences crowds,” notes Coval in the film, “because her presence is that demanding.”

And then there’s Nate Marshall from Whitney Young High School, who grew up with drug addicted parents but has become a renegade slam poet, slamming since age three — even referring to himself in one poem as “Langston Huge.” An LTAB veteran, his final poem was an ode to both slam poetry and the festival:

“I thank this forum for help making me so strong/For letting me talk about sex, drugs, basketball and moms/Fond farewell to this chapter and for all the joy and laughter/This for every kid whose voice has been louder than a bomb.”A legend in his own right, this intellectual from the projects is notably the one to beat.

Representing Northside Jewish youth is Adam Gottlieb, a long-haired free-spirit whose positivity transfixes everyone he meets. “Adam Gottlieb is one of the best writers we’ve ever had at Louder Than A Bomb,” Coval says. “And one of the most sincere, genuine, gentle people I’ve ever come across.”

Gottlieb performs an individual poem in the film: “She stands with her toes hanging off the edge of the stage/Her whole presence squared like praying/Like she can’t blink even with the force of a storm behind her eyelids, shoulders shift around each other like lovers/Fierce like she’s shouting before she even opens her mouth.”

Aside from the fierce talent chronicled in the documentary, perhaps one of the most poignant journeys is the one taken by the kids from Steinmentz High School. This pants-dragging, bling-sporting team from “the wrong side of the tracks” has the charm of the stereotypical underdog. Their first time in competition, the Steinmenauts came out of nowhere as the winning team in LTAB 2007, and the pressure they put on themselves for 2008 is palpable. Nevertheless, their presence onstage resonates powerfully.

In one scene during the festival’s very tense semi-final round, the Steinmenauts debate which of their pieces will have the greatest impact. A team performance of “Ten Graves” — a lyrical meld of rap and song — shocks the audience with its dark content and passionate execution. “Ten. Nine. Eight/(Seven) year old boy put (Six) feet deep in the (Five) foot coffin wondering what (Four) while (Three) grown men have (Two) drop by and he dodges a couple of bullets but (One).”

The Steinmentz kids cull from a far more desperate set of experiences. These are kids who are admittedly different from the rest of the competitors, but their innate ability to slam is unreal; they are wired with the hip-hop spirit.

The sense of community created by spoken word in a still-segregated Chicago is what ultimately makes this festival such a success. “I think for young people in the city — where they are either segregated or separated because of socio-economics and race, or because they are self-isolated in their own home technology — the demand for a public space that values the oral poetic has become really important. Not only to young people, but to humans,” says Coval.

Siskel and Jacobs may have been going out on a limb in creating their first feature film on a then little-known poetry festival in Chicago, Illinois. But they have helped to spotlight a band of heroes — not only in this particular group of kids, but among youths of all ages and circumstances who use slam poetry to make their voice heard.

“What Kevin and they have created, in some ways it’s so … it seems a little messy,” says Jacobs. “Which is part of its charm, but it’s so incredibly well thought out and powerful. And you may not like slam poetry, and you may have certain notions of good poetry and bad poetry, and I suppose that’s true; but when you see how brave the kids are, whether they’re amazing or whether they’re sitting up there with their piece of paper and are shaking and nervous, it doesn’t matter. You’re just so moved by it.”