SAIC’s Therapeutic Arts and the Global Alliance for Africa

By M.J. Villamor

Art Therapy Department Chair Catherine Moon did not know about Global Alliance for Africa (GAA) until she received a call from them in 2008. Shortly after, she was on a plane to Tanzania. In July 2006, GAA, a program helping communities provide sustainable care and support for orphans and other children affected by HIV/AIDS, created an art program in East Africa. GAA set up weekend art camps in Kenya and Tanzania, with hundreds of children participating and local artists serving as guides. The artists helped the children focus on visual art, vocational art, music, and dance. GAA wanted to add a therapeutic arts component to their program, and Moon was the person that GAA needed to make that happen.

Art Therapy Department Chair Catherine Moon did not know about Global Alliance for Africa (GAA) until she received a call from them in 2008. Shortly after, she was on a plane to Tanzania. In July 2006, GAA, a program helping communities provide sustainable care and support for orphans and other children affected by HIV/AIDS, created an art program in East Africa. GAA set up weekend art camps in Kenya and Tanzania, with hundreds of children participating and local artists serving as guides. The artists helped the children focus on visual art, vocational art, music, and dance. GAA wanted to add a therapeutic arts component to their program, and Moon was the person that GAA needed to make that happen.

Her goal for that first year was to get a sense of the cultural context, and understand GAA’s needs. In order to visit more places in Tanzania, Moon stayed three and a half weeks, one more week than the length of the program. She observed that East Africa was a place of ethnic division, a place where she says there is still lots of tension.

Her goal for that first year was to get a sense of the cultural context, and understand GAA’s needs. In order to visit more places in Tanzania, Moon stayed three and a half weeks, one more week than the length of the program. She observed that East Africa was a place of ethnic division, a place where she says there is still lots of tension.

“In general,” Moon said, “the people in Kenya are very concerned about the tense political situation there and a recurrence of the violence that occurred after the last election. The people in both countries are concerned about poverty and government corruption.”

She says that as a Mzungu (white person), she was hassled on the street, but when in people’s homes or visiting their work site, she was treated like a queen. “They always wanted to feed me, even the poorest of the poor were generous. We also had a lot of fun with people—making jokes, singing, dancing, poking fun at each other.” She was amazed by the hospitality and affection showed by both adults and children. “Men even hold hands in public.”

But Moon also observed the trauma the children experience. She describes it as “complex, compounding, and prolonged for these kids.” She explains that “not only do they experience the often protracted and suffering-filled deaths of their parents, but they are parts of families and communities that have experienced multiple losses. Some have to become the caregivers for their younger siblings.” These circumstances compound the financial hardships that the majority of people in East Africa already experience. Institutional care is rare, so children are taken in by relatives or become heads of households. Others are left homeless. “When they move in with relatives,” Moon said, “they often contribute to an already overcrowded household and add to the financial burden, which can lead to a feeling of not belonging and a lack of emotional support. Because of financial worries, the child may be forced to drop out of school… so he or she can earn money for the family.”

Add to this the stigma and bullying that go along with being an orphan and the trauma is compounded. Many children, are never told their parents have AIDS or have died of AIDS, so along with grief, they may experience confusion, reinforcing the sense of isolation. “In some cases, the kids also experience abuse, neglect, domestic violence, child labor exploitation, substance abuse by a caregiver, and their own medical issues due to being HIV positive,” Moon said.

When she returned to Africa this summer, she wrote a training manual containing very basic counseling concepts and art therapy theory to help GAA’s African therapeutic artists to address and understand the African children’s trauma and grief. Moon says that it was great for her to write. She just said what she knew at the most basic level.

Moon doesn’t think that the African artists needed help understanding the children’s grief. “What happened was that we shared ideas about how to not only help children express and manage their grief, but also build skills, a sense of agency, and resilience,” she said.

Besides writing the training manual. Moon worked with kids. Moon says, “Our art making with the kids while we are there is either for enrichment, or connected to these trainings” and that working with the kids together with the African artists is part of the training.

Two artists, Sane and Eunice, had already opened up their own studios to local kids. “For them,” she said, “the trainings affirmed their intuitive ways of working, added to their theoretical knowledge, and gave them legitimacy within their communities. It was important for them to have a certificate of completion because people in their community have been suspicious of their work with kids, thinking they were just doing it to gain access to humanitarian aid.” In their collaboration with GAA, Sane and Eunice will start a weekly therapeutic arts program in Kibera, a slum in Nairobi. They will travel there once a week while still working with the kids where they live in Tanzania.

Maeda, another trainee on faculty at Bagamoyo College of Arts, already had a sports and arts program in Kenya. Maeda had been doing drama, music, and dance with children, but “he used it purely as a diversion from their troubles.” Moon worked with the kids from Maeda’s program in training him. According to Moon, Maeda believes in the “arts to distract” from the turmoil existing in these kid’s lives. Moon states, “It was a new perspective for him to think that art could also be a way for children to address and possibly resolve their troubled feelings. In countries where death, particularly death from AIDS, is seldom discussed with kids, we had to have some discussions about how to open up these avenues of expression for children while still respecting the beliefs and practices of families and communities. On the other hand, we talked about how art expression can occur in a coded form, so that no one needs to know its meaning other than those people the child chooses to tell. So the role of the therapeutic artist is to create a safe space where kids can express whatever needs to be expressed, without necessarily having to speak about difficult or taboo topics.”

To have Africans teaching Africans is Moon’s goal for GAA’s arts therapy program, as well as financial sustainability, which is why there is also a vocational component to the program. Art forms are to be sold to fund the program. A woman’s weaving co-op exists, and these women are emissaries for GAA’s mission.

Andrea Koch, Art Therapy Alumni (2009), joined Moon for the 2009 trip. Koch was moved by Moon’s experience, and spent $4500 on an airline ticket. She helped Moon train the African artists in basic counseling techniques to weave that into what they were already doing.

Koch said “the experience was really cool because it really strengthens my belief in the usefulness of art therapy, expands my belief of what art therapy can be, and what it can do.” Koch was able to “really focus on art making and working with people that are in need.” Originally an art major in college, it was those things that interested her in the field of art therapy. Koch states, “I learned so much. I learned more, a ton more, than I ever can teach these people.” When asked whether it was worth it, considering the cost of graduate school, she said, “I don’t regret it at all. If I could come up with the money to go back every year, I would do it.”

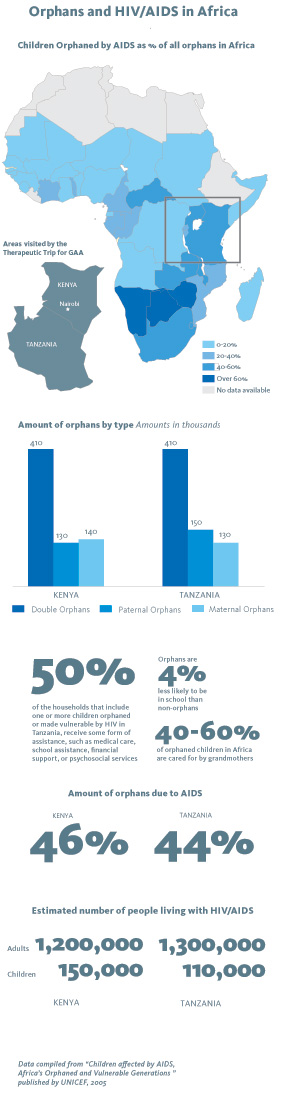

Infographic by Javier López

Thank you for a well written article that captures the essence of the therapeutic arts program in East Africa.

However, I want to point out that Angela Lyonsmith, part-time SAIC faculty for the Art Therapy Department, is co-author of the training manual mentioned in this article,co-facilitator of the trainings, and a key person in the ongoing development of the therapeutic arts program.

Also, some people might notice that there was a mix-up with the captions and photos in the article, as they don’t match!