Named after the patron saint of music, “St. Cecelia” uses audio recordings and music to examine the intricacies of sound through the experience of a deaf artist. Deaf since the age of ten, Joseph Grigely makes work that deals with the way sound “looks” and the relationship between hearing and remembering.”

The centerpiece of the MCA exhibition is a two-channel video installation called St. Cecelia (2007). The piece is composed of two wall-sized projections of the Baltimore Choral Arts Society Choir singing songs like “My Favorite Things” and “Jolly Old Saint Nicolas.” One video is true to the original lyrical arrangement, while the other has been rearranged, with some of the words replaced by different words that look the same when lip read.

Grigely’s purpose in composing visually parallel lyrics for familiar songs was to reflect on our “infinite capacity to misunderstand each other.” He has achieved an interesting and often absurdly hilarious result. For example, “Cream colored ponies and crisp apple strudel” becomes “Creamy exponents and newspapers too,” while “Johnny wants a pair of skates” changes to “Johnny was a bastard child.”

Remembering is a Difficult Job, but Someone’s Got To Do It (2005) also deals with memory and interpretation, creating a similarly humorous result, but from a more personal perspective. A video monitor on the floor shows Grigely being interviewed. The interviewer asks him to remember and sing out loud songs that he knew the words to before losing his hearing—mainly jingles from advertisements and the theme from Gilligan’s Island. Disparities between his memory and his ability to actually recall these tunes present themselves; the music has not stopped playing in his head, but his ability to accurately carry a tune has changed.

Working in collaboration on many of the “St. Cecelia” works with his wife and fellow artist, Amy Vogel, Grigely has succeeded in installing a truly multimedia experience at the MCA, and one worth checking out for anyone who can see, or hear, or remember.

“St. Cecilia” will be on view through February 22 at the MCA, 220 E. Chicago Ave.

Interview with Joseph Grigely

Joseph Grigely is a professor at SAIC and the head of the Visual Critical Studies department. I caught up with him to discuss “St. Cecilia,” humor, memory and meaninglessness at his home in Chicago in early January.

Brian Wallace: I wanted to start by addressing humor. It seems that much of “St. Cecelia” has an element of humor, silliness, a kind of poignant absurdity. Can you talk about the necessity of humor in your work? In art? In communication?

JG: The thing is, people are social creatures, and we like to laugh. There are so many kinds and levels of humor too, and it’s been intertwined with many other complex human emotions in art for… how long? Look at Chaucer: so serious and so funny. Look at Shakespeare: same thing. I don’t think it’s a lot different for visual art. A lot of good artists manage to dance the fine line between being serious and being funny—Maria Eichhorn, Adel Abdessemed, Andreas Slomoniski, Olaf Bruening, Peter Land, even Douglas Gordon—they all do this so well. Of course, they all do it differently. But that’s the beauty of it all. You don’t find this kind of humor so frequently in work by American artists; the Brits came up with David Shrigley, and we came up with Joseph Kosuth. Maybe we don’t drink enough?

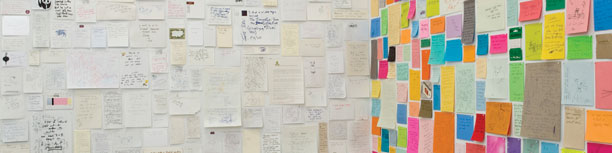

BW: This issue of F Newsmagazine is concerned with memory. Several of the pieces in “St. Cecelia” deal with handwritten notes, it seems that what you have here is a written documentation of things that hearing people can simply say or hear and then cast aside never to be revisited again. Having access to such a database of conversations, both profound and mundane (and everything in between), do you think about your personal memory through these notations? Do you think they serve as illustrations? Are they something else entirely?

JG: Yes, the conversations hold memory—a lot of it. I was just spending Christmas with an old friend, and we were eating cheese and crackers, and I said to her: do you remember the time years ago when you wrote down, “Yes, we ate your Triscuit!” and she said, “Uh, no.” So, maybe it’s the wrong kind of memory?—as I remember all these little inconsequential things people say to me. I suppose also the conversation papers are drawings. Drawings of speech: something that’s not quite writing because of how the words lack context—there’s no beginning of a conversation, there’s no end, just the fragments of it. To me it’s the most meaningless stuff that’s most interesting in the end, like when someone writes down “Bye” or something like that… or “fuck you!”—things that really just don’t get written down, and don’t need writing even.

BW: You just mentioned meaninglessness. There is a segment of “St. Cecelia” that mentions “meaningful meaninglessness.” Can you expand on that concept?

JG: Well, it’s a lot like the idea of the still life, which Norman Bryson describes as a kind of “rhopography.” It’s from the Greek rhopos, which means ordinary everyday stuff that otherwise gets trampled afoot. So there’s dead fish, fruit peels, shelled nuts, cabbages, stuff like that. Ordinary conversations are not a lot different. When people think about language and art, they think a lot about profound stuff, but it’s the un-profound conversations from everyday life that have this rhopographic quality. One of my favorite conversations was with Ellen Cantor. We were in her studio in Jersey City one day, and about to head into NYC, so Ellen said, “wait a minute.” So I waited and waited, and she came back and wrote: “I had to set up cat litter.”

BW: Do you think that the ability to choose what is meaningful, to choose which memories to hold on to is a collective human experience, or are we all involved with a more chaotic relationship with memory?

JG: Uh… I really don’t know. I think memory varies for all of us—some people remember words but others remember better the tone with which they are spoken—so I find it hard to generalize about this, or even about the “collective human experience.” All I can think of in relation to that phrase is the fact that our economy has turned into collective crap, and we are all feeling it bad.