by Rachel Sima Harris

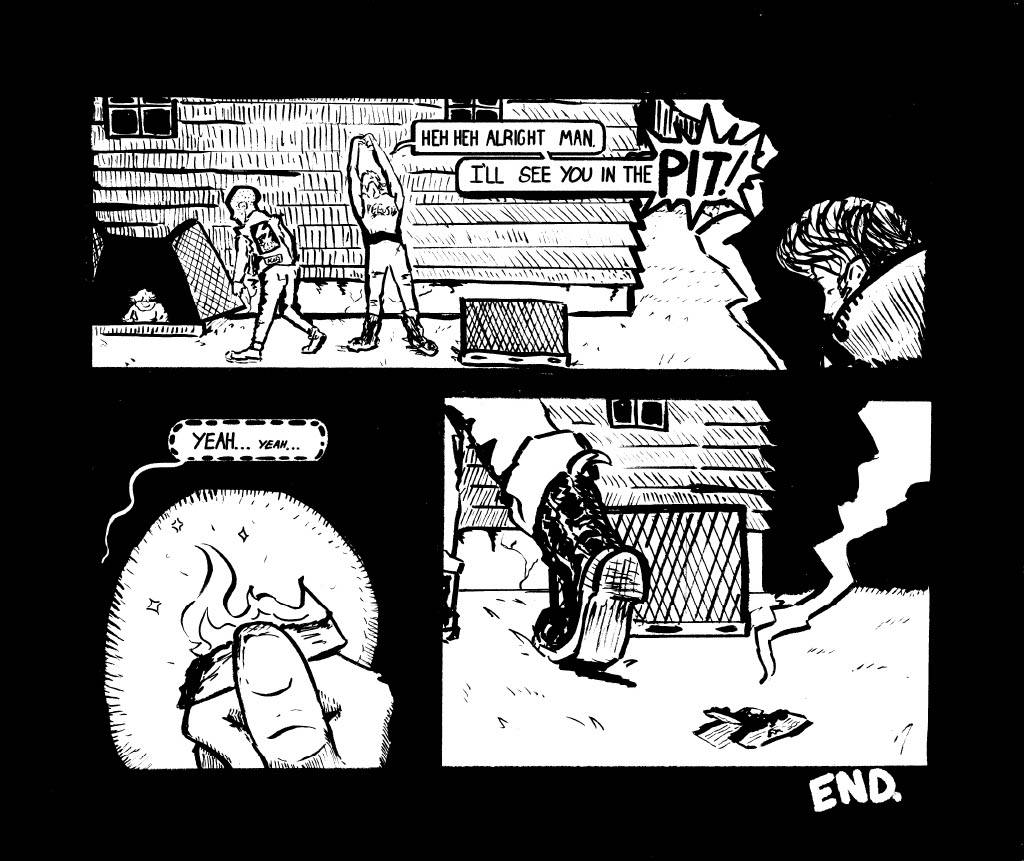

The portrait that incited the controversy

On May 11, 1988, School of the Art Institute of Chicago student, David K. Nelson Jr., showed his painting Mirth & Girth: a portrait depicting an overweight Harold Washington in a bra, panties and garter belt, at a private student exhibition at SAIC. Nelson’s stated intention was to respond to what he viewed as the deification of the African American Mayor, who passed away several months prior to the show.

The painting, whose name was derived from a social club for overweight gay men and which echoed the snide insinuations of some of Washington’s rivals at the height of Chicago’s racially charged Council Wars, so offended many members of the African American community that several black aldermen arrived at the exhibition demanding that it be taken down. Before the painting was finally arrested by the Chicago Police Department, a crowd had developed outside the School’s entrance and a shouting match between predominantly white art students and predominantly black members of the community was underway.

While the painting was only up for a few hours it incited one of the largest race relations and First Amendment controversies in the history of the School. In a Chicago Tribune interview, Nelson told Toni Schlesinger that he “didn’t want this to polarize a community.” But polarize he did. In the days, weeks and months following the display of the painting, SAIC students held a rally protesting the confiscation of the painting, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan characterized the display of the painting as a “total disrespect of our feelings and our community,” a group of clergymen led by the head of Operation PUSH called for SAIC to create a review policy to prevent offensive portraits by its students from being shown in the future, and Alderman Robert Shaw led a chorus of voices for change stating that “only 6 percent of the Art Institute’s 1,400 students are black and we want that changed. The Institute would have been more sensitive to the concerns of the black community if there were more blacks both as administrators and teachers and as students.”

In the aftermath, Nelson sued the city for violating his First Amendment rights and was awarded $95,000 in a settlement. School President Tony Jones created a task force “to review our progress and to assist in the continued execution” of a program to increase minorities in enrollment, faculty and staff. Art Institute Board Chairman Marshall Field issued a formal apology for displaying the painting and agreed to consider demands that the school hire more black administrators and recruit more black students.

In connection with this month’s memory theme, we asked James Britt, Head of Multicultural Affairs, to reflect on how we understand this racially charged memory when we think about diversity at SAIC then and now.

Interview with James Britt, Head of Multicultural Affairs at SAIC

Rachel Sima Harris: Around the time of this controversy, and perhaps as a response to it, the Illinois Alliance of Black Student Organizations called for racial parity with regards to faculty and student enrollment at SAIC. The president of the Illinois Alliance of Black Student Organizations James A. Brame called the Art Institute a “closed bastion of white male Western cultural supremacy.” Can you speak to that perception of the Art Institute, and perhaps how it’s changed (if you feel it has changed) in the years since then?

James Britt: I think we still have a ways to go as an institution. A clear example of this is reflected in the number of non-white persons in upper level positions at the School. We do not have one person of color at the Vice President level; we do not have one person of color at the Dean level; and there are two people of color at the Director level. One of those persons at the Director level is me, and one would assume the Director of Multicultural Affairs would most likely be a person of color because of the nature of the job, so to a certain degree my presence skews the statistic. Over 30% of our student population are students of color, yet this diversity is not reflected in our full-time staff and faculty positions. Almost 20% of our student population is Korean, however the presence of Korean administrators and faculty is virtually non-existent. It’s disconcerting to me that post-Mirth & Girth we are still wrestling with these issues. I point these facts out not to be pessimistic, but to bring light to issues that are obvious and to challenge us as a community to develop viable solutions to address these disparities.

RSH: How does diversity (or lack of it) impact the educational experience of students at SAIC?

JB: Diversity is paramount to the success of any student; without it the learning process is impeded, one becomes intellectually and emotionally stagnant, and unable to effectively navigate his/her life to the fullest in this multi-faceted society in which we live. It challenges an individual to continually refine his/her perspective, which is essential to learning. We live in a multi-racial world, it would behoove students just from a practical standpoint to develop a basic level of cultural competency; and it’s imperative as an institution we provide those opportunities for learning in the classroom, residence halls and other communal spaces.

I hope students at least acquire a baseline understanding of cultural knowledge, but I think the ultimate goal is to achieve a level of understanding or empathy where one is able to comprehend another’s point of view. That’s what I find most disappointing about Nelson’s work; that he failed or refused to acknowledge the thoughts and feelings of black Chicagoans. The City has a long history of racism and Washington’s ascent to the Mayor’s office contributed greatly to the healing process for everyone. To create a piece like this in such a cavalier manner, shortly after the man’s death and in light of other racial incidents that recently surfaced, was pouring salt on an open sore. Maybe if Nelson had provided more context for his work this could have been avoided. Maybe if we as an institution had provided a richer cultural educational experience for Nelson this would not have occurred. You ask how does diversity impact the educational experience; Nelson’s lack of accountability for his work is representative of that.

RSH: SAIC has taken on several diversity initiatives since the controversy. What were those and how have they affected change at SAIC? Do you think they’ve made a difference in the type of educational experience students have at the school or the art that comes out of it?

JB: I only know of one diversity initiative that was in place before I arrived four years ago: Diversity Leadership Teams (DLT’s). There were three groups, each designed to address diversity-related issues pertinent to students, staff and faculty. The idea was noble, but they weren’t very effective, so they dissolved shortly after my arrival. We’ve had a few permutations of the group, but nothing with longevity.

What has worked are the numerous smaller initiatives individuals or intimate groups of staff and faculty have created. For example: Professor Kym Pinder started the Archibald Motley Fund, which provides scholarships to black students at SAIC through private donations; Robyn Guest, Secretary for the President, heads our internship program with Perspectives Charter School, which serves under-represented middle- and high-school students in Chicago and the surrounding area; SAIC alum Leroy Neiman provided funds to educate high school students from disadvantage communities about art; SAIC alum Tim Nuveen, donated money for the International Student Learning Center; Associate Director of Undergraduate Admissions Carolina Wheat has been working with Congressman Bobby Rush’s Art competition for youth in predominately African American communities; Andres Hernandez, Drea Howenstein, Patrick Rivers, Nicole Marroquin and a number of our students have worked with various cultural institutions/programs in the City by teaching courses, engaging in community work, among other things; OMA implements initiatives like our annual exhibition with the African American Alumni Assoc. and the South Side Community Art Center.

I think these initiatives have made a tremendous difference for those students who have participated in them. However, I would still like to see something happen on a larger scale that reaches out to the entire SAIC community.

RSH: With regard to race relations, what things still need to change at the school and how do you envision those changes becoming manifest?

JB: We need to begin to have candid conversations about diversity. I think there’s this belief that we are inherently culturally progressive because we are an art school, however this is not the case. If it were we would see greater representation of diversity in the areas I mentioned earlier, and we would not continue to have the same discussions about diversity that took place during the time of Mirth & Girth.

My first year we put together a program called Conservatism and Art. It was a panel discussion made up of conservative students and faculty who identified themselves as Christian, Republican and white. I chose this theme to illustrate a few points:

1. Even people in the majority can be a minority

2. Liberalism does not equate to openness; if one only accepts liberal views is he/she liberal?

3. Diversity affects everyone, not just students of color, women, or LGBT students.

I thought the program was highly successful. One of my colleagues commented that she had never seen so many white male students at an OMA event. A “nontraditional marginalized” student approached me afterwards and said he enjoyed the discussion but he didn’t see what it had to do with diversity. He made my point exactly; he did not connect diversity to his life experience because he isn’t a part of the socially sanctioned marginalized groups. We need to move beyond this limited viewpoint, and weave diversity into the fabric of our existence.

RSH: What do you feel the role of “Black History Month” is (generally but also specifically at SAIC)?

JB: The concept of Black History Month bothers me. The history of black Americans should be recognized everyday, in the classroom, through art history classes, lectures, etc.—it diminishes the black experience to relegate it to one month, the shortest month in the year I might add, and to make it a subset. This is the problem with many diversity initiatives. The moment a “minority” group is highlighted it devalues their experience, because if that group was a part of the larger experience and fully integrated there would be no need to make this distinction. Why isn’t there a white history month? Why not give every group a month? A truly heterogeneous community incorporates everyone’s experience, the positive and the negative. This to me is the essence of true diversity, when everything and everyone is completely integrated and there is a cultural reciprocity that takes place. This doesn’t mean the dominant group gets to choose what aspects of another group they want and disregard the rest. It means there is a mutual sharing of experiences between all groups.

RSH: Finally, what lessons were (or still need to be) learned as a result of the controversy?

JB: I would pose this question to the individuals at the School who were present during the Mirth & Girth episode; have we changed, and what did we learn from the incident? Is there a better relationship between the School and the African American community in Chicago? Are students more culturally competent and able to understand the sociological implications of race, identity and sexuality? I’m unable to answer this question completely since I was not present during this timeframe. I think there is a greater level of sophistication in how we would address something of that nature if it occurred today, but I think that may be more a result of our evolving pluralistic society and the skills we’ve acquired to communicate with each other, as opposed to something we’ve implemented as an institution.

I wonder how many of us have these conversations with our friends who share different cultural backgrounds from our own, or examined how heterogeneous/homogenous our circle of friends are and why? We don’t think about these things until a David Nelson or Jeremiah Wright moment occurs, but they were there all along. I would hope as a community we can have more honest dialogue with one another.

These discussions require knowledge beyond the cognitive level; emotional intelligence must be present too. Put your emotional intelligence to use the next time you have a conversation with someone. Before you start generating reasons why your point of view is correct and theirs is wrong, ask yourself, “Why does this person think this and what evidence supports their position?”

Every year I have African American students ask me how come we do not have more black students at the School. What I find interesting is that I never see the same number of non-black students asking me the same question. The point I’m making is that these issues have to be collective.

I was one of the student-gallery attendants during that time. I was there when Danny Davis and his people marched into the school like a bunch of storm-troopers and took the painting off the wall. I was also there when the other “whatshisname” had his American Flag exhibit and had to put it back on the floor every time the US military people folded it up… So art is all about pushing the 1st Amendment rights envelope, right?

Why can’t we just talk about the OBVIOUS need for diversity and equality and representation, and the proposals for actions we’re going to take to change the school (and the art world in general)? You know, without giving this guy yet another extra minute of fame?

Hey, btw, is there an Asian American Alumni Association? I don’t remember getting mailings / seeing info about it…