Photo by Mary Louise Killen

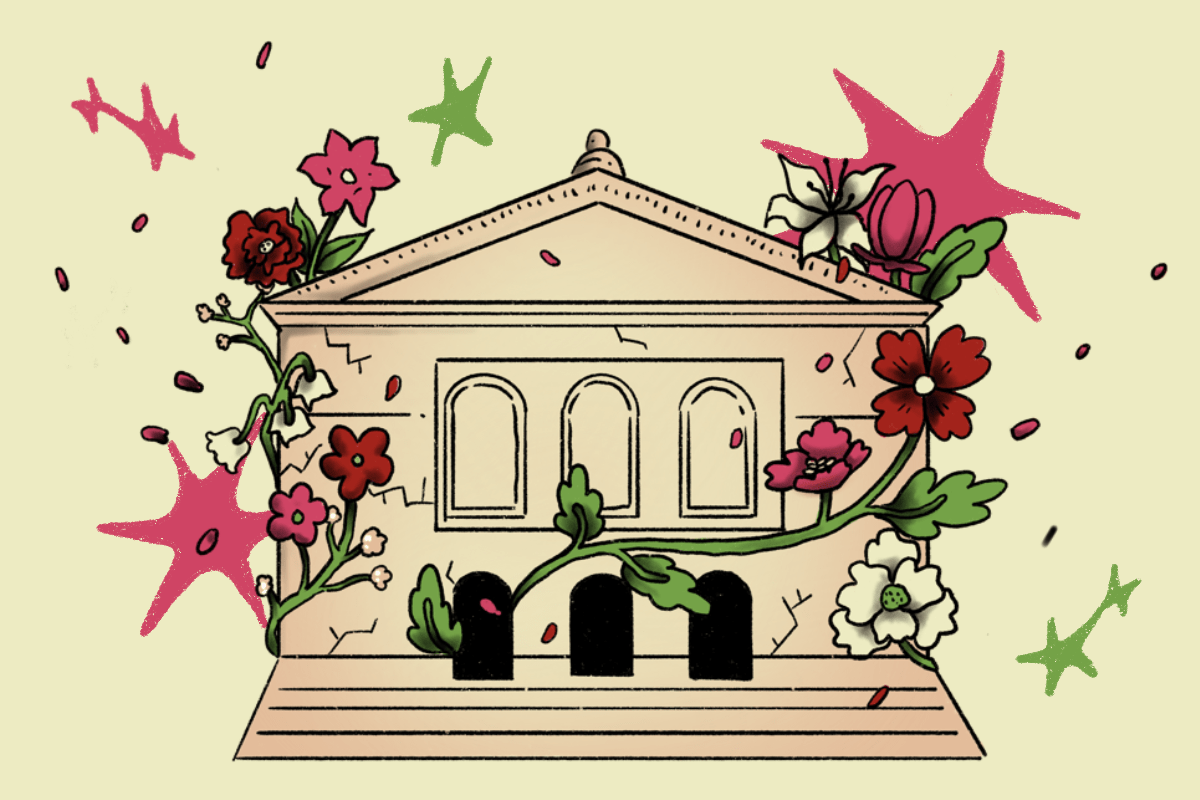

The challenge of greening museums

The U.S. Green Building Council, a not-for-profit organization that promotes sustainable architecture, has created a certification process for green building and development projects for structures of every type. According to the Council, the economic benefits of building green are numerous. For example, an initial investment of $4 per square inch in green systems or materials yields a benefit of $58 over the course of twenty years, with savings accrued in operations and maintenance, energy, emissions and water, according to the Council’s website. Because museums are high-energy consumers, integrating green practices makes sense, especially in the face of rising energy costs.

The Green Building Council’s certification process for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) involves the rating of a building in five categories, as well as four different levels of certification, ranging from “certified” up to platinum. The Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) is currently attempting to achieve LEED silver certification for their new Modern Wing, designed by Renzo Piano. Erin Hogan, AIC’s Director of Public Affairs, says that achieving LEED certification “would certainly be a recognition of our efforts to be a leader in sustainable museum practice.” According to their website, green initiatives for Piano’s design include a sunshade, or “flying carpet”, that is specifically designed for the building’s location to garner ideal light conditions for the upper galleries during the day. Automatic adjustments are made by an interior lighting system, and there is as a double-window front wall, which provides light and ventilation. The AIC also installed solar panels on the roof of its current building ten years ago.

As green initiatives in museums become more commonplace, so do texts and dialogue on the subject. The American Association of Museums annual meeting this month, for instance, features a “Green Steps” logo that highlights lectures and workshops that deal primarily with sustainability. The AAM is currently working on a new book entitled National Standards and Best Practices for U.S. Museums, which includes a small section on green initiatives: “There is not any national standard regarding green design at this time, but it will be an item for discussion by the field in the coming decade.” The text elaborates further on some first steps that museums can take towards becoming more green-conscious, but it is far from best practice guidelines.

Setting long-term goals and brainstorming green practices is the goal of Chicago’s Green Museums Steering Committee, formed in June 2005 by the Office of the Environment, and most major Chicago museums are members. Certain conditions must be met in order to join, as laid out in the Green Museum Certification Requirements, made available through the Office of Environment. Three prerequisites involve the purchasing of green or local materials, the establishment of a “Green Team” which meets regularly to discuss and implement green operations, and an outreach component that educates the public and museum employees about sustainable and green practices. Members must also either “incorporate sustainable technologies or processes into capital improvement projects” or have shown in the past year, or plan to show, an exhibit that addresses environmental concerns.

Chicago museums have come up with a variety of ways to integrate green practices into their routines. Shedd Aquarium, for instance, has an extensive composting program that helps fertilize their flowerbeds, as well as a unique soy-based roof panel that helps cool their building in the summertime. Robert Weiglein, an exhibition designer at the Field Museum, has incorporated multiple sustainable components into the George Washington Carver exhibition, which opened in February 2008. For example, instead of constructing new drywall to divide the exhibition space, Weiglein decided to use mesh fabric panels that are wrapped over aluminum frames. Weiglein emailed F Newsmagazine a statement detailing the use of green design in his exhibition, and claims that when the exhibition ends in five years, the fabric walls will be donated to a free lending program for public schools in Maine.

Finding a new use for such materials marks an important concern for the exhibition process. Often exhibition-design pieces are custom-made, making them inappropriate for resale, or have been manipulated in such a way that they cannot be traditionally recycled. Don Meckley, Director of Production and Facilities at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), is well aware of these difficulties and agrees: “It is important to find a final resting home for the unused materials that can’t be recycled directly.” Sheetrock, used to construct temporary walls, is one material that is incredibly difficult to reuse. The same was once true for steel wall studs, but because the metal market is strong right now, the MCA has been having no trouble recycling those that are no longer usable. Because the process of “recycling” building materials can sometimes be inefficient and difficult, Meckley is a strong believer in finding new uses for materials, and is seeking a partnership with Habitat for Humanity in which the MCA could provide used materials for housing construction.

Material Exchange, a Chicago-based collective, attempts to find new use values for materials that have become trash. Although part of their mission involves the redistribution of materials to increase material life cycles, they are also artists concerned with the opening up of dialogue, of getting viewers to see waste not as unusable but rather as a “misplaced resource.” As part of the Massive Change exhibition at the MCA, Material Exchange did a project entitled 12 x 12, in which they collected waste materials from the museum to create useful sculptures. The goal, according to member Charles McGhee Hassrick, was to make “art that can go back into the world, change value, and serve a new purpose. We are interested in revaluing things that have lost their original use.”

Becoming a green entity is difficult in any situation, and museums are in a particularly tough spot. As green technologies become both more advanced and economically viable, however, and as new resources are sought for the redistribution of materials, the possibilities grow. Chicago museums, it seems, are up for the challenge.