Sex and violence, specifically as they occur in the paintings and drawings of artist Nancy Spero, were the topics of the well-attended April 6 lecture by art historian Mignon Nixon at SAIC. Nixon, Senior Lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art and a Clark Fellow at the Clark Institute, drew upon her interest in and knowledge of psychoanalysis to create a particularly enlightening analysis of the content and influence of several of Spero’s works.

Nixon began with an analysis of Spero’s painting “Homage to New York” (1958), a critique of the masculine politics of the New York School of the fifties. Consisting of a phallic tombstone inscribed with the initials of pre-eminent Abstract Expressionist painters—several of them women—flanked by two figures sticking out their tongues, the work prominently and boldly contains the phrase “I do not challenge,” as well as the artist’s name. Nixon compared the derisive iconography of this work to Sigmund Freud’s writing on jokes, and the way in which such seemingly slanted comments often contain critical ties to both reality and the unconscious. It was this sort of duality that inspired Virginia Woolf to encourage women writers to implement derision as a way to find their own voice in what was undeniably a man’s world.

Shortly after creating “Homage to New York,” Spero moved to Paris with her husband, painter Leon Golub whom she met as a student at SAIC. While abroad, Golub painted and Spero tried to find time for both painting and raising children. Nixon proceeded to examine one such work, “Les Anges, Merde, Fuck You” (1960), which she saw as representative of the sort of discomforting alienation often experienced but not spoken of in motherhood. These sentiments were particularly resonant in a post-World War II culture where the psychological significance and emotional vacillation of motherhood were examined with increasing curiosity by psychoanalysts and society alike.

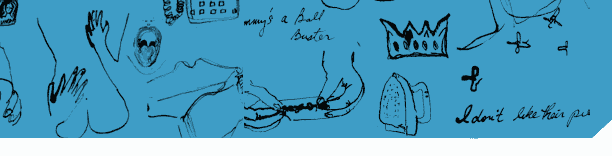

The final works examined by Nixon were several paper, ink, and gauche drawings that Spero created upon her return to the United States in the sixties. Abandoning what Nixon termed her “elegiac mode,” Spero instead gravitated toward themes that were angry and scatological in nature. In such works, the artist hoped to convey her anger at America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, which she protested as a mother whose sons could potentially be sent into combat. Visually resembling children’s drawings, Spero’s anti-war work contains frequent sexual imagery, including phallic bombs and penile airplanes. Nixon identified the experiences articulated in Spero’s work with a position of silent frustration and related them to the shell-shock—often termed “male hysteria”—experiences of men directly involved in the war.

It was this sort of silent frustration that found its way continuously into Spero’s work, Nixon noted. From the quiet participation of women artists in the New York School, to the seemingly irreconcilable position of a woman who is both a mother and an aspiring artist, to the citizen who opposes a war over which he or she has no control, Spero’s work effectively and repeatedly articulates the frustration of involuntary passivity. Nixon articulated, in a way that was soft-spoken, well-supported, and hugely insightful, the continuities and significance in the work of this particular artist.