By Michelle Zis

Born in Chicago in 1922, Golub, and his paintings, show a lifelong concern with human violence.

Considered the most important American post-war political painter, Golub will not be easily replaced.

Golub received both his BFA and MFA from SAIC on the GI Bill after serving as a cartographer in the U.S. Army during WW II. Prior to the war, Golub studied art history at the University of Chicago.

Golub met his wife artist Nancy Spero SAIC and they married in 1951. SAIC Dean Carol Becker describes Golub and Spero as artists who just continued to make the work that they thought was important without caring about what was fashionable in the art world.

In the 1950s, when Abstract Expressionism dominated the art scene, Golub was involved with a group of painters known as the “Monster Roster.” They painted distorted figures and claimed “an observable connection to the external world and to actual events was essential if a painting was to have any relevance to the viewer or society.”

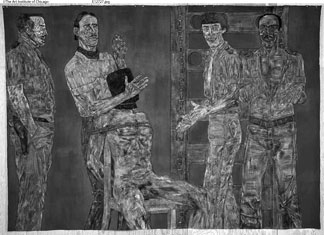

Applying that credo throughout his entire career, recently, many connections have been made between Golub’s paintings and the images in the media from Abu Ghraib prison. At once, Golub’s work seems both prophetic and yet a sobering reminder that the theme of men using intimidation and brutality constantly exists in history and in the world.

“He was very interested in power, who has that power and how it is being used,” says Becker. She explains that Golub also saw both the person being brutalized and the aggressor as victims.

Beginning in 1959, Golub and his family moved to Paris after teaching for a short while in Indiana. The large-scale historical paintings of French masters David, Ingres, and Courbet influenced his work. When Golub returned to New York five years later, he began a series of large-scale paintings of nude classical figures battling without weapons that he called the “Gigantomachies.”

Back in the United States, finding themselves profoundly affected by the Vietnam anti-war protests and media images of the gruesome war, Golub and his wife immediately got involved. “Leon and Nancy were political activists and extraordinarily generous to organizations. They were great citizens of the world,” states Golub’s Chicago dealer Rhona Hoffman of the Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

Golub’s painting began to directly respond to the war. The “Napalm” series depicted burnt and mutilated bodies. The napalm bomb wounds made the figures more relevant to the current situation, but unlike victims of the Vietnam War, the figures were nude.

Still not close enough, Golub wanted to paint something more immediate. “In war, men are clothed. They kill with guns and rockets. It took until 1972 to work out a solution that had contemporary relevance and historical resonance,” stated Golub. The result was the three monumental paintings, the “Vietnam” series. The distressed surfaces of Golub’s paintings reflect his theme of man and power. Golub would apply many layers of paint. Scraped off with a meat cleaver, the paint becomes ground into the canvas.

During the 1970s Golub painted over 100 portraits of political, military, religious, and corporate leaders, from Nelson Rockefeller to Fidel Castro.

Using elements from these portraits Golub returned to painting large canvases of mercenaries and interrogation. After remaining outside the radar of the art scene for many years, in 1982 these paintings were exhibited in Golub’s first New York solo show in twenty years.

Describing those works, Jon Bird, author of Leon Golub: Echoes of the Real, says, “Golub was only doing what he had always done–speaking back to power and documenting its politics and repressions. In this, he discovered a means to adapt the tradition of history painting to incorporate the technologies and techniques of the news media and cinema.”

Contrasting the images he creates of brutality, humiliation, and power, those who were friends of Golub have just as much to say about his personality as they do his artwork. “Although he clearly was fascinated by the brutality of the male psyche,” says Ahearn, “he was in person a very sweet, soft-spoken guy who was a great listener. Leon was always ready to hear about movies, hip hop and art gossip over a bottle of wine.”

Becker describes Golub as “hilarious.” Furthermore, one cannot speak about Golub without mentioning his wife. “They had one of those unique, almost impossibly successful marriages between two artist. They had enormous respect for each other,” says Becker. Becker also describes how the couple lived like graduate students in their New York loft. She describes the entire place as a “giant studio.” “The whole place was about work.”

“They seemed to thrive on the edge, working hard at all hours in their adjoining studios with no taste for the comforts of a couch or easy chair,” says Ahearn. “Nor did Leon find comfort in repeating his past successes, but he was always pushing his painting to new unknown places.”

Hoffman says, “When I moved to Chicago around 1960, the second work of art I bought was Burnt Man from the ‘Burnt Men Series.’ It was not until 1980 that I started to represent his work. I still feel totally dedicated to the work and to the man. He will be a voice sadly missed.”

Read an interview with Leon Golub

Leon Golub Memorial

Tuesday, November 23, 6:00-8 PM

Ballroom, 112 South Michigan Avenue

ˆKeynote address by Professor Jon Bird

ˆScreening of the film Golub: Late Works are the Catastrophes by Kartemquin Films ˆRefreshments

Image (Interrogations II, 1980/81) courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

November 2004