Laurie Palmer Speaks to F Newsmagazine About Her Excavations of U.S. Mining

In 2003, at the beginning of the Iraq War, Laurie Palmer, longtime Professor of Sculpture at SAIC, began a research project to understand, through her own partiality and subjectivity, the processes that people carry out to transform the freely given materials of the earth into private commodities. She spent that year under the auspices of a grant at The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, reading materialist philosophies about mineral extraction sites and theories of land. “That was an unbounded research year that was really wonderful and kind of confusing,” she says. “I had hoped that the book would just happen in that year, but it didn’t and that was ten years ago.”

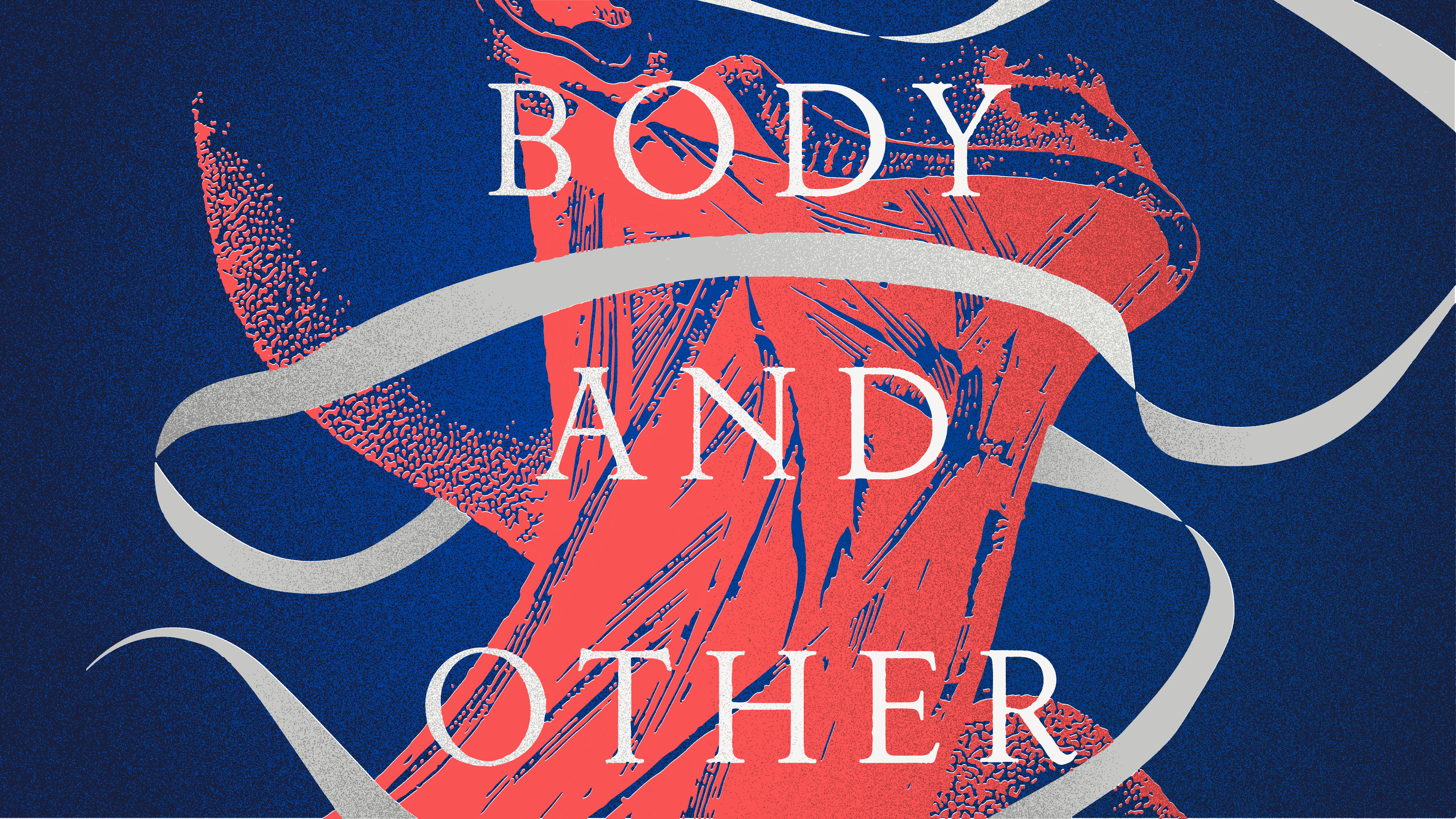

In the Aura of a Hole, published this spring by Black Dog, is the result of a decade of Palmer pursuing access and personal knowledge of mining operations through a series of visits or attempted visits to mines. She says that the process of writing the book was about “wanting to go to these sites, rather than going online and getting some more information and then digesting that information and spitting it back out.”

For almost every visit, she needed a guide. “Those relationships became really intimate really quickly, because if you go underground, you’re totally dependent on this person. Even getting in someone’s truck and driving somewhere, basically, you are really close for a period of time. I enjoy what that sort of access via a personal connection provides,” she explains. “Some of these guys (and they were mostly guys) were definitely schooled to give me company lines, but with others I felt a more of an excess of their own engagement with their work and the materials they were working with. They have to be extremely knowledgeable to be working with these materials in pretty dangerous ways. There’s some- thing wonderful about that artistry, and their enjoyment of their, if not mastery, engagement with the material.”

Driven by curiosity around the interactions between raw elements and microphysics, exchange value and labor, environment and privatization, the book is peppered with references to ancient and contemporary philosophies and descriptions of chemical processes that serve as seedlings for inquiries and ruminations. The way these dense subjects are approached is both informative and personal. Palmer avers, “There is a kind of non-constrained approach that I think you can take as an artist that I think is boundary crossing — where the ‘I’ and the world become permissively blurred. Some of these processes might become more digestible, more interesting even, once they’re considered through a subjectivity that is trying to make sense of them herself.”

Each chapter is titled with a commonly commoditized element: Carbon, Silicon, Aluminum, Lead, Sodium, Calcium, Sulfur, Phosphorus, Chlorine, Potassium, Uranium, Helium, Iron, Copper, Iodine, Silver, Gold, and Mercury. “Altogether,” she says, “I have had the idea in the back of my mind that if I had the right balance of elements and the right range of kinds of processes and places across the U.S., that it would create a whole with an internal structure that, although partial, provides a foundation to understand these processes.” The ties that bind the chapters and the elements are complex, relating to labor, mundane chemistry and physics. However, Palmer is not trying to elaborate an encyclopedic knowl- edge, rather each chapter elaborates a slightly different concern. She hopes that the “reader might be able to put some ideas together from reading these different chapters about the interdependencies of different industries on each other as well as our dependencies on the earth.”

Palmer journeys to sites within the U.S. where these elements are mined, to the land and the extraction centers. Access to the mines was not always possible. Her curiosity often met the “wall between industry and those of us who use and depend on these things. Part of my desire was to try to open that wall, for myself even.” Sometimes there were no impediments to access. “When I went to visit the lead mines in Missouri, which is where most of U.S. lead has come from for almost the last hundred years, one arm of the operation was, interestingly, generous. They made a spread of lunch for me, with these rolled up ham and cream cheese things, and presented a Powerpoint with my name on it. It was really wild! I felt really confused, because lead mining is one of the dirtiest industries and my guide here was virulently anti-environmentalist. There’s a lot of ideological rhetoric that can come out in these encounters. But I didn’t have to sign anything that said I had to show them anything I wrote. Some places would ask me for that and I wouldn’t go because I didn’t feel like I could do that.”

Other times corporate headquarters would respond defensively, offering information by phone only but denying entry to the mines. “One place in Georgia I really did get the door slammed, not literally, but on the phone, several times. It’s not that surprising, but it’s part of what interests me.” In Georgia, Palmer was investigating the industry of Kaolin, a white clay thick with aluminum, that is legendary for its displacement of people from their homes. Kaolin is “one of these things that goes into many different products, but we never re- ally see it. You might know it as a face mask, ceramicists know it for sure, but it’s also in milkshakes and rubber plugs in the bathroom. A lot of these things, if they don’t get sold directly to the public, they don’t really have any public face. They didn’t want me anywhere near. In that part of Georgia, there’s the stereotypical red clay, and then you go down a red clay road through the trees and there would be a blinding white hole with this beautiful blue turquoise water in it.” Once the mining of the Ka- olin is finished, the holes fill with water. “It’s really wild, this landscape, full of all these holes. All those people who just had to leave.”

Throughout In the Aura of a Hole, Palmer conjectures about the co-creative relationship of life and inorganic matter in forming and occupying the world. In the chapter on sulfur, she writes, “When the earth was considered a body, mineral resources grew like plants in her hidden womb, and that womb was sacred enough to inspire both prayer and apology. […] Even solidified ‘earth juices,’ so called by Georgius Agricola, including saltpeter, ‘nitrum’ and sulfur, even these less precious but still important materials might replenish, minerals like plants having an active living dimension. […] Enlightenment science brought a new understanding of the earth as machine, and in this mechanistic paradigm, matter is passive, dead, inert.” Through her researching of these materials, Palmer has considered the shifts in understanding our relationship to materiality through what we do. People co-create the world as they rearrange and rethink it, but it has never been a one-way system.

“Geology and bacteria created the earth together,” she says. “They’re not separable. Part of what I was thinking about was how matter moves between our bodies and certain elements move the earth and back and forth. I was thinking of that relation as central to the book. Part of what happens with these extraction processes is a massive re-arrangement of things that took a long time to find equilibrium. Not that everything should stay the way we found it, but it’s a huge disruption to separate this one little element from hundreds of thousands of tons of other stuff. In order to do this, it’s really quite violent. I do outline that I basically understand our bodies and the earth as continuous. That’s completely in line with how I see. I see us as limbs of the earth, and our illnesses as symptoms. When we enact such violent rearrangements of the earth, we liberate toxins that had been kept in check in equilibrium.”

That these rearrangements have repercussions environmentally on our physical health through pollutants is evident. The fact that many of the sites of extraction are on indigenous land is a horrendous trespass, but also suggests “some kind of hope” for Palmer who

notes some of the Western Shoshone and the Iroquois continue to claim parts of New York State as land that they want returned in part in order to heal it. In that, “It seems that there is a possibility for different relation- ships with these sites,” she says.

The holistic approach to her topic weaves moments of her personal history with the history of consumer relationships with the elements and the specificities of her encounters with industrial complexes. Though the accounts of mining and chemical processes are accurate, her entry points to the subject bring the reader closer to experiencing chemistry in its more emotional connotations.

“I don’t have any pretensions to imagine a massive rethinking of our relationship to materiality, although I would like to,” she laughs. “But I do think that some understanding, and this is something that I’m interested in theoretically and in bringing to students in classes to try and understand it better, is that idea of continuity with material and collaboration with matter, rather than mastery or dominance over it. That shift in relations is critical.”