Chicago’s overlooked experimental film history at the Illinois Institute of Design

By Brandon Kosters

In 1937, former Bauhaus teacher Laszlo Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus School in Chicago. Ultimately renamed the Institute of Design (ID), the school became part of the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1949. The school was one of the first in the US to encourage experimentation in film, yet the works produced there remain relatively obscure.

In 1937, former Bauhaus teacher Laszlo Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus School in Chicago. Ultimately renamed the Institute of Design (ID), the school became part of the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1949. The school was one of the first in the US to encourage experimentation in film, yet the works produced there remain relatively obscure.

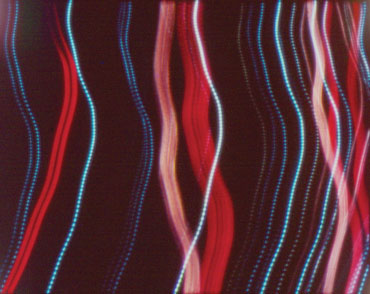

Amy Beste, SAIC faculty member and curator of “Conversations at the Edge,” is trying to change this. On October 1 and 2, Beste presented “Visions in Motion: Filmmaking at the Institute of Design, 1944-1970,” an event consisting of two programs that screened at the Gene Siskel Theater, showcasing works from the school. ID filmmakers used a variety of methods to produce stimulating and cost-efficient student films. Some artists produced cameraless animations, some documented the natural world in a unique way. For his film “DL # 2,” Larry Janiak coated film with rubber cement and exposed it, producing work that evokes the likes of Norman McLaren. For his film “Motions,” Harry Callahan utilized in-camera multiple exposure techniques to superimpose images of water over mundane b-roll footage. Yasuhrio Ishimoto and Marvin Newman’s “The Church on Maxwell Street” is a stunning black-and-white film that documents musicians playing to a predominantly African-American congregation on the street.

Originally structured in the same format as the Bauhaus, the ID offered a preliminary course similar in structure to the first-year program at SAIC. “Initially,” Beste said, “advertising arts, photo, and film students adhered to the rubric of the Light Workshop. Moholy pushed the medium of light as the root of film and photography.” Light was “the medium that drove those other iterations of the medium.”

Beste suggests that one of the reasons this history has been largely overlooked might have to do with access to national distribution. “In the mid-1960s,” she said, “inspired by Filmmakers Cooperative in New York and Canyon Cinema in San Francisco, a group of Chicago makers (a number of them, Institute of Design alumni) established the Center City Co-op which distributed Chicago and Midwestern work.” She says. “The organization disbanded in 1976 and it seems that a number of folks did not place their work elsewhere, so that this whole period of works produced in Chicago just disappeared from circulation. So, at a time when US ‘experimental film’ was being canonized, a number of Chicago filmmakers were literally out of circulation.”

Resources at the ID were limited and the artists embraced the challenges this presented. Wayne Boyer, who attended ID as both a bachelor and graduate student and who is now a Professor Emeritus at University of Illinois at Chicago, says that when he arrived at the school in 1955, “all of the film equipment was in storage and there was no one to teach it. But that was OK because of the experimental nature of the curriculum, where you were encouraged to combine media. This is what stimulated us.”

Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo’s daughter and a scholar of her father’s work, confirms Boyer’s recollections. “When [Laszlo] started the school, he couldn’t afford to pay any faculty. It was really a shoestring operation, and it remained that way for about a year,” she says. “The school gradually took ground and started to work, then along came World War II.” However, even with several faculty members and students drafted, and the scarcity of materials and funds, “Moholy managed to keep the school alive.” The school was one of the first to emphasize experimentation as an effort to both create a body of work that would provide a counterpoint to and potentially revitalize commercial/mainstream movies and media. “Janiak is a great example of this kind of training,” says Beste. “For many years he worked at Goldsholl studios (now largely forgotten, but at the time a nationally-recognized and important design studio in Chicago), where he, along with Wayne Boyer, was encouraged to apply his experiments to advertising and industrial films. The studio was headed by Mort and Millie Goldsholl who both were graduates of ID and directly applied the Bauhaus ethos. The work they produced ended up in trade shows, short commercial films, and in television ads for national distribution.

Boyer and Janiak met at Lane Technical High School in Chicago in the 1950s. Some of their instructors were former teachers from ID, and they inspired both of them to pursue film. One of their instructors from Lane Tech got Janiak and Boyer into conferences for designers in Aspen, Colorado. During their second conference in the late 1950s, Janiak met one of his biggest influences, who was also at the conference. “The Goldsholls we’re running it. Millie [Goldsholl] invited us to go to an ice cream parlor. As we were walking there she said, ‘Oh, by the way, I’ve asked Norman McLaren to come over.’ And so he showed up and we’re having ice cream sodas.” One of Janiak’s films that McLaren saw in Aspen was what Janiak calls “an attempt at abstract film where I drew on blockout and then used Dr. Martin color dyes absorbed into the emulsion,” producing “abstract linear patterns.” “[McLaren] was a really sweet man. He did say, ‘You know, that’s one of the best films I’ve seen made in 16 mm.’ Well, that was a nice compliment but see, he did everything in 35 [mm]!”

Both Boyer and Janiak went on to study at ID in the mid 1950s. In 1968, Janiak began teaching experimental film and design animation at the ID. In the Bauhaus tradition, Janiak allowed his students to have creative license. “My course structure was pretty loose,” Janiak says. “I counted on the students to come up with their own ideas. Most of these students had never made a film before, and most of them never did again. There were some that went on commercially and experimentally, but nobody ended up famous or anything like that.”

Artists producing films at the ID sustained essentially two practices as filmmakers. “While there was a presence in Chicago of filmmakers who were pointedly anti-commercialism,” Beste says, “it seems to me that people had these dual careers: producing experimental films, and supporting themselves through the industrial film sector. Their experiments were happening in both arenas.”

Beste believes that a reassessment of avant-garde film history to include these works would produce quite a different picture of experimental film in the US. “Chicago was a center for industrial and educational filmmaking. In fact, for many years, it was considered the Hollywood of non-theatrical film. A number of ID faculty and graduates worked and applied their experimental vision to these industries. Films produced in this industry were (and still are, to some extent) considered highly ephemeral. Companies made them for a specific purpose — to teach a certain lesson, sell a certain product, explain a certain process. Once that purpose was no longer current, many of these films (and their filmmakers’ experiments) were just thrown away.”

“It’s only in the last 15 years or so that scholars and historians have begun to examine these films as both historical artifacts and important aesthetic contributions to our broader media culture,” Beste said. “I think looking at works produced within this system has the potential to change the way we think about the role of experimentation in media and the operation of the avant-garde in the US.”