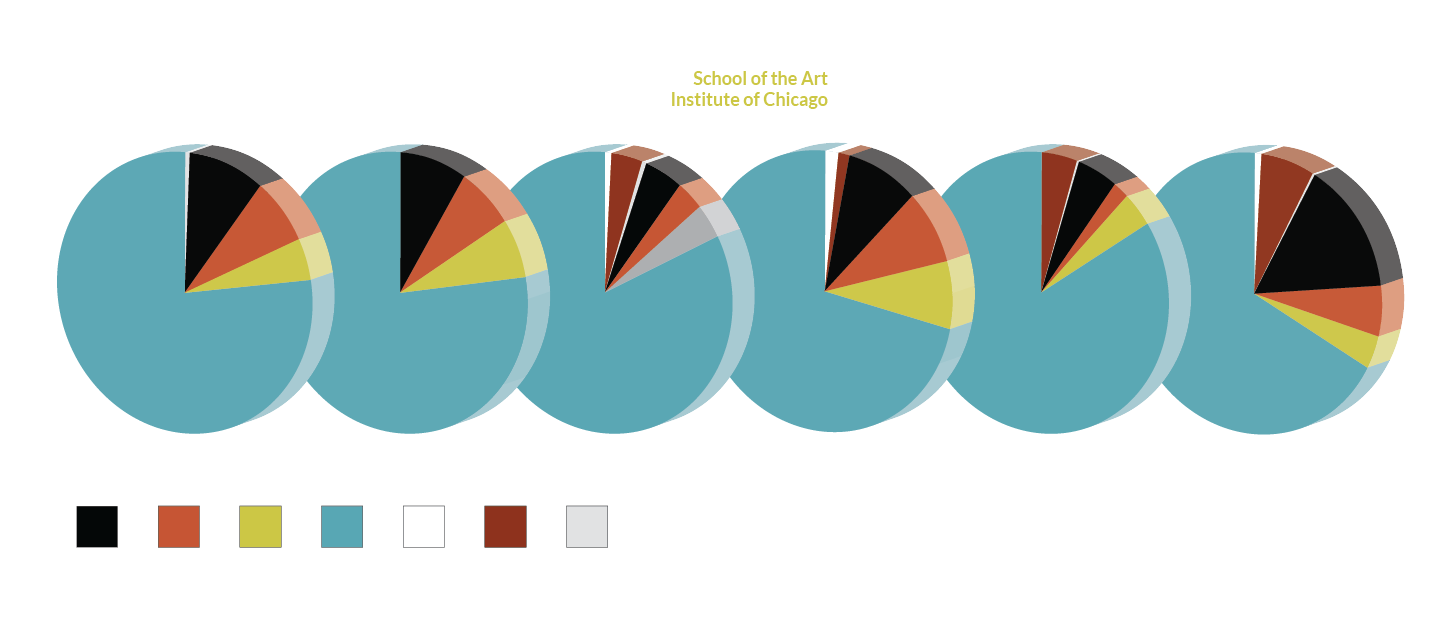

Full-time faculty demographics for CalArts, Pratt, RISD, SAIC, SVA, and Temple University, 2018. (Data from National Center for Education Statistics.)

holloway often feels “torn between trying to save my energy to actually help [students] in the classroom, which is where I’m hired to help [them], and saying, ‘you don't actually have a resource here,’” by sending students to faculty with whom they may have already had negative experiences. “That's the failure of the part-time-heavy system, especially when the demographics of the school look like they do,” she said.

The low percentage of faculty of color at SAIC is consistent with national averages for higher education, as well as percentages at other art schools in the United States. SAIC’s faculty body is overall slightly more diverse than national averages for degree-granting postsecondary educational institutions.

While national averages for the enrollment of students of color, and particularly Hispanic students, have increased in the past three decades, this rate has not been reflected in changes in faculty makeup. In contrast, faculty members in the U.S., and particularly full-time faculty members, remain disproportionately white and male. According to a fall 2017 report by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the research arm of the Department of Education (DOE), 81 percent of all full-time professors are white, and the majority of them are also men. 8 percent of full-time professors are Asian/Pacific Islander men, and 3 percent are Asian/Pacific Islander women. Black men, Black women, and Hispanic men each accounted for 2 percent of full-time professors. Hispanic women, American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, and respondents who identified as two or more races, each made up 1 percent or less of the total number of full-time professors. The DOE does not collect information on sexual orientation, and its definition of gender identity is limited to “male” and “female.”

“Any time we need to speak to issues of race, that weight falls on BIPOC.”

Increased support for and hiring of BIPOC faculty was part of a set of demands calling for structural change published on July 7 by Black faculty at SAIC. The letter, which can be read in full here, calls for the resignation of “all parties involved” in the school’s prolonged mishandling of provost and senior vice president of academic affairs Martin Berger’s use of the n-word in a quote during a public presentation in September 2018. “We are extremely dismayed by the facts of what it has cost — two years of staff, student and faculty labor, financial resources, and an international Black Lives Matter Movement — to create this opening for racial justice at SAIC,” the letter reads.

The letter provides a detailed timeline and comprehensive list of changes to be made. Among other points, it calls for the establishment of a tuition fund for Black students in memory of Lynika Strozier, the SAIC lab coordinator and Field Museum employee who passed away on June 7 from COVID-19, establishing a campus space for BIPOC students, clarifying and “decolonizing” SAIC’s relationship to its classroom space and programming in the predominantly Black neighborhood of North Lawndale, and increasing the capacity and number of positions in the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI).

When contacted for comment, multiple Black faculty members who co-wrote the letter expressed feelings of exhaustion, and commented that the act of writing the demands was also a form of unwaged and emotional labor that they were performing in the service of the broader school.

“A whole lot of labor is asked of our BIPOC faculty,” said Allie n Steve Mullen (Associate Professor Adjunct, Department of Art and Technology Studies, Department of Film, Video, New Media, and Animation, Department of Sound, and Department of Liberal Arts), who is white, and uses all-inclusive pronouns. “Any time we need to speak to issues of race, that weight falls on BIPOC. Just the labor of the conversation, and the labor of the work around diversity, falls primarily to our BIPOC faculty, staff, and students.”

Like other faculty F News spoke with, Mullen also pointed to the school’s moderate achievements with respect to some forms of diversity, a perceived desire within the school to do better, and a frustration that far-reaching changes still hadn’t been accomplished.

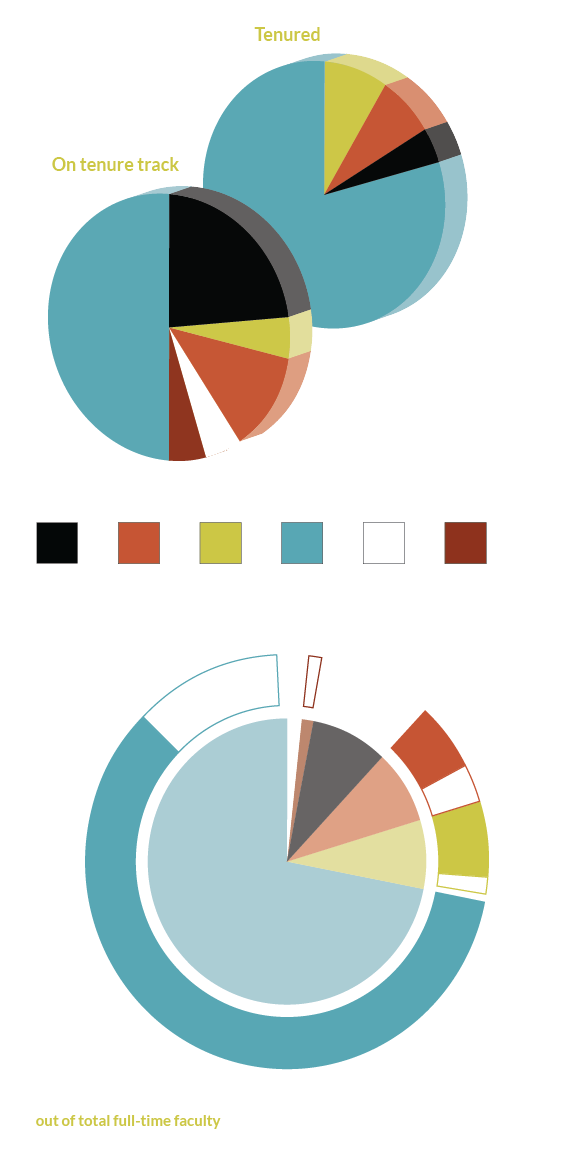

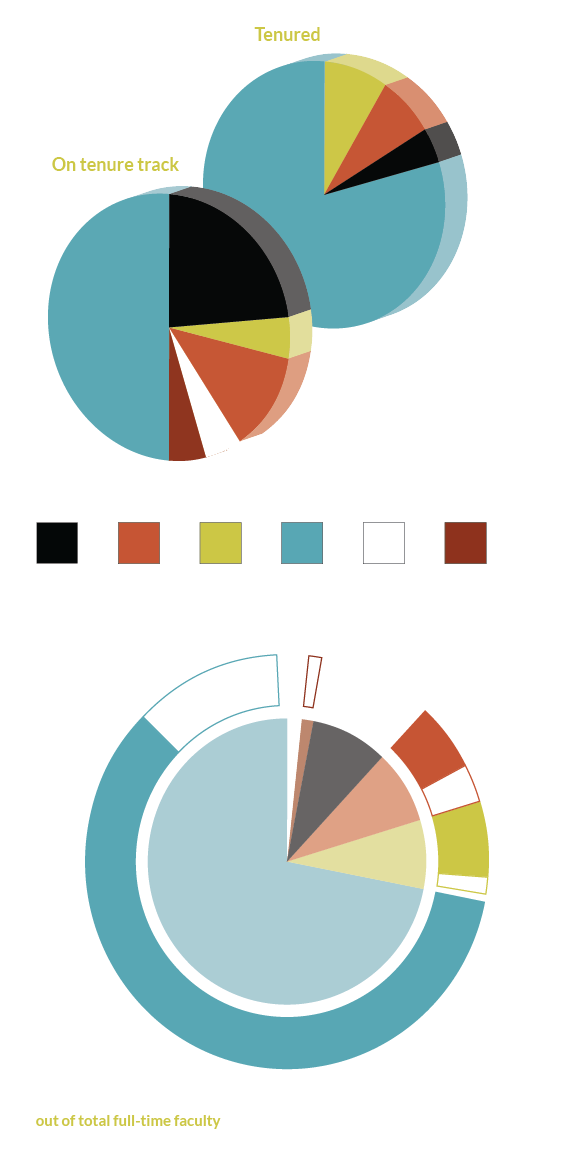

Full-time instructional staff: Racial demographics breakdown, for both tenured and on tenure track

“We have made some progress. From a gender identity standpoint, there are more trans faculty here, certainly, than there were twenty years ago,” said Mullen, adding that there were still issues with support for non-gender-conforming community members. “This is one of the things that frustrates me — I think we're much slower with race than we are with gender identity.”

Although there is little difference between the ratio of white faculty to faculty of color among part-time and full-time faculty at SAIC, tenured faculty members are significantly whiter than non-tenured faculty members.

In the past several years, however, the school has made a significant attempt to grant tenure to more faculty of color. Both Provost Berger and faculty members F News spoke with credited Jefferson Pinder, former Interim Dean of Faculty and current Director of DEI, for recognizing and working to change the disparity among tenured faculty members.

Upper-level administrators have also made public commitments to center BIPOC students, staff, and faculty. During the height of the spring’s Black Lives Matter protests, Berger sent out a campus-wide apology email for the 2018 n-word incident. In it, he and the school committed to “redouble efforts to increase our hiring, retention, and promotion of people of color [and] ensure equity in compensation,” as well as to advance anti-racism work in other ways.

When asked what metrics and timeline he would use to measure whether he was meeting these goals, Berger described some of the initiatives he was proposing or working on with other school entities, like the Faculty Senate, department heads, and the Faculty Contract and Tenure Review Board. Measures he described included mandatory diversity statements and anti-bias training for all faculty searches, selecting more diverse “pools” of candidates for open faculty positions “so that chairs in need don't just call people they know, but [instead] draw from a pre-vetted group of qualified candidates,” and “published criteria for each department’s tenure and promotion standards, to ensure consistency of treatment of all applicants.”

Berger added that part of measuring the commitment also involved hiring an outside consultant to examine wage differences and other disparities that impact SAIC faculty. Human Resources plans to conduct a similar outside investigation in fall 2020.

Berger also told F News that he had requested an assessment of his own work on diversity, equity, and inclusion to be part of his annual performance review, and that he would like the school to consider making this a part of reviews for all staff in management roles, from department chairs to upper-level administrators.

“We draw up our job descriptions in such a way that we simply replicate ourselves.”

“This would be a concrete way of ensuring that all of us are engaged in the work we value, and that when we fall short, we are given the feedback and resources needed to improve,” he told F News via email.

Beyond initiatives like creating diverse pools of applicants, Mullen attributed one of the obstacles to faculty diversity to the job candidate hiring process, criticizing its reliance on a cookie-cutter image of what makes for a strong applicant. By centering the importance of credentials from other elite institutions, which remain inaccessible to many low-income and BIPOC applicants, for example, these searches can still be deeply exclusionary.

“What that privileges is people who are already invested in the system, who have already benefited from systems that have been in place for hundreds and hundreds of years,” said Mullen. “We draw up our job descriptions in such a way that we simply replicate ourselves.”

Instead, they suggest, departmental job searches and other employee recruitment at the school should expand their definitions of suitability, looking at skillsets and more diverse ways of gaining experience than institutional affiliations.

But the most significant changes will have to be bigger than a handful of promotions or new hires, said Mullen.

“It’s one thing to put people in positions of leadership. It’s another thing altogether to empower them and to really give them the power to make change, and to not have to run it by anybody else,” said Mullen. “Until we actually give them decision-making power in ways that are actually going to fundamentally change the institution, we haven't really shifted anything.”