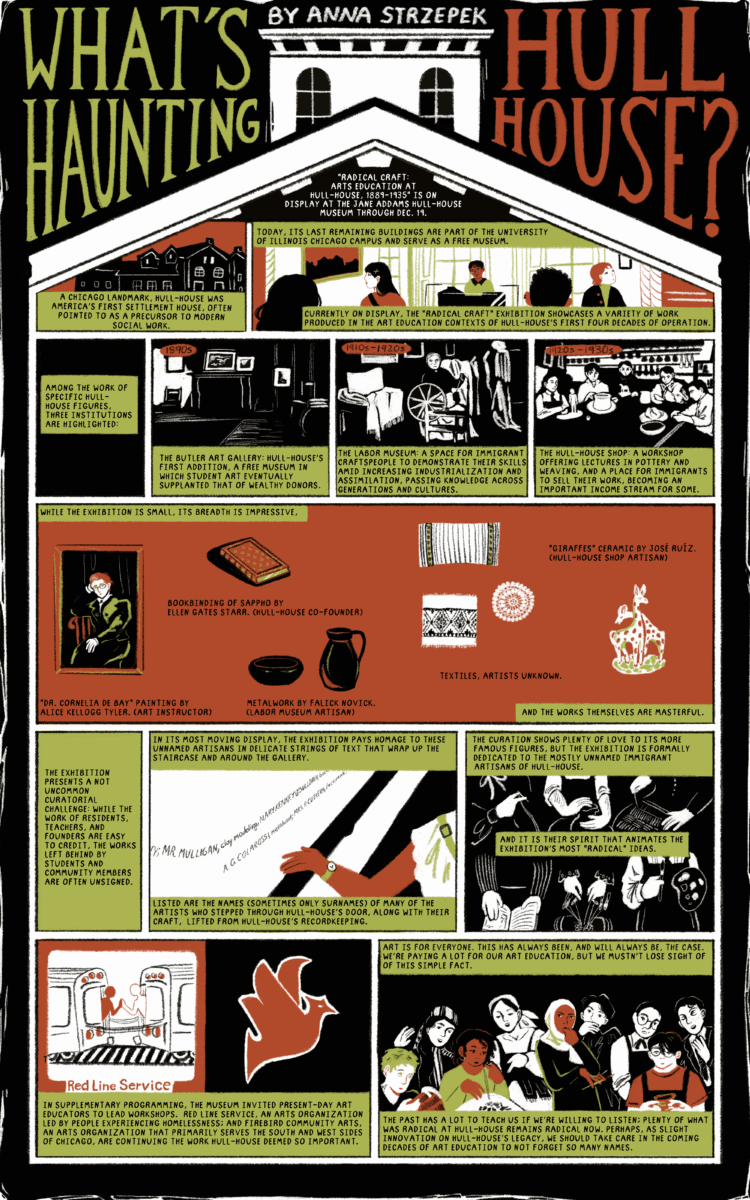

Panel 1: “Radical Craft: Arts Education at Hull-House, 1889-1935” is on display at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum through Dec. 19.

Panel 2: A Chicago landmark, Hull House was America’s first settlement house, often pointed to as a precursor to modern social work.

Panel 3: Today, its last remaining buildings are part of the University of Illinois Chicago campus and serve as a free museum. Currently on display the “Radical Craft” exhibition showcases a variety of work produced in the art education contexts of Hull House’s first four decades of operation.

Panels 4,5,6: Among the work of specific Hull House figures, three institutions are highlighted:

The Butler Art Gallery: Hull House’s first addition, a free museum in which student art eventually supplanted that of wealthy donors.

The Labor Museum: A space for immigrant craftspeople to demonstrate their skills amid increasing industrialization and assimilation, passing knowledge across generations and cultures. (Pictured is Honora Brosnahan)

The Hull House Shop: A workshop offering lectures in pottery and weaving, and a place for immigrants to sell their work, becoming an important income stream for some. (Pictured is José Ruíz (far right) and several unnamed ceramics students.)

Panel 7: While the exhibition is small, its breadth is impressive.

“Dr Cornelia De Bey” Painting by Alice Kellogg Tyler. (Art Instructor)

Bookbinding of Sappho by Ellen Gates Starr. (Hull-House co-founder)

Textiles, Artists Unknown.

Metalwork by Falick Novick. (Labor Museum artisan)

“Giraffes” Ceramic by José Ruíz. (Hull House Shop artisan)

And the works themselves are masterful.

Panel 8: The exhibition presents a not uncommon curatorial challenge: while the works of residents, teachers, and founders are easy to credit, the works left behind by students and community members are often unsigned.

Panel 9: In its most moving display, the exhibition pays homage to these unnamed artisans in delicate strings of text that wrap up the staircase and around the gallery. Listed are the names (sometimes only surnames) of many of the artists who stepped through Hull House’s door, along with their craft, lifted from Hull House’s record keeping.

Panel 10: The curation shows plenty of love to its more famous figures, but the exhibition is formally dedicated to the mostly unnamed immigrant artisans of Hull House. And it is their spirit that animates the exhibition’s most “radical” ideas.

Panel 11: In supplementary programming, the museum invited present-day art educators to lead workshops, collaborating with Red Line Service, an arts organization led by people experiencing homelessness, and Firebird Community Arts, an arts organization that primarily serves the South and West Sides of Chicago. These organizations, and many more, are continuing the work Hull House deemed so important.

Panel 12: Art is for everyone. This has always been, and will always be, the case. We’re paying a lot for our arts education, but we mustn’t lose sight of this simple fact.

The past has a lot to teach us if we’re willing to listen; plenty of what was radical at Hull-House remains radical now. Perhaps, as a slight innovation on Hull House’s legacy, we should take care in the coming decades of art education to not forget so many names.

(Pictured from right to left: unnamed Syrian spinner, Hilda Satt Polacheck, Alice Kellogg Tyler, Jesus Torres, Hilarion Tinoco.)