“The Language of Beauty in African Art” currently on display from Nov. 20, until Feb. 20 at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), presents an artistic survey of over 250 sculptures and objects through themes of gender, presentation, and the artistsʼ identities. This show covers decorative statues, functional items—such as pipes, dishware, ritual objects, masks, and hats—and more. The collection reminds us not only of the lesser-shown artistic value in African cultures but how these works were acquired and showcased.

Art institutions, the AIC being no exception, have fetishized, objectified, misinterpreted, and mistreated African art. Western narratives and standards of beauty have defined these works for centuries in a master narrative of art history. Such bias represents these works through a Hegelian lens of primitivism and an eternal past. Not to mention, it has been over a decade since the museum has had an exhibition focused on African art.

This show serves, in many ways, as a rightful step to acknowledge African and Black voices from an instituteʼs perspective. The AIC engaged this significant exhibition with Chicagoʼs Black and African community by working closely with cultural leaders such as Olateju Adesida, Solomon Adufah, T. Ayo Alston, “Tepaka Lunda” Conde, Kahil ElʼZabar, Brendan Fernandes, Maudlyne Ihejirika, Adedayo Laoye, Patric McCoy, Vershawn Sanders-Ward, and Mirabel Wiryen. These efforts included a guided audio tour and text and photographs to buttress the exhibit and provide context for viewers.

Advisor Solomon Adufah put special emphasis on this collaborative creative aspect, saying, “It was important to provide direct feedback, as the nuances of the exhibition present a parallel context to my practice.”

Indeed, for many of the members of this collective, along with much of Chicago and the Black community at large, this exhibit brings many questions of identity, spirituality, and community to the surface. These conversations are necessary to facilitate and create art spaces to override the persisting dominance of Eurocentric narratives.

Upon entering the gallery, complex representations of gender are evident as you find yourself immersed in male and female figures, and these pieces immediately subvert the Western patriarchal narrative. In sculptures such as Olowe of Iseʼs “Veranda Post (Opo Ogoga)” from Nigeria, an elongated woman stands over the seated king and his second wife as a symbol of strength and wisdom. The two wives are guiding figures for their husband. The much smaller seated kingʼs feet, however, barely touch the ground, hinting at his reliance on women within this hierarchy.

In other pieces, like “Portrait of a Queen (Wife of King Njike)” from the Batoufam Kingdom in Cameroon, women appear strong and fierce with their children. Such presentation — flourishing in this space — is a common motif among African sculptures, again asserting female strength and significance. Men, too, are celebrated throughout the exhibition — in large monumentally scaled robes from Senegal and Nigeria, we see highly embellished pieces that celebrate the “aesthetic of bigness.” Hats, too, appear to signify status, along with robes, making these objects into symbols of not only status but gender and masculinity.

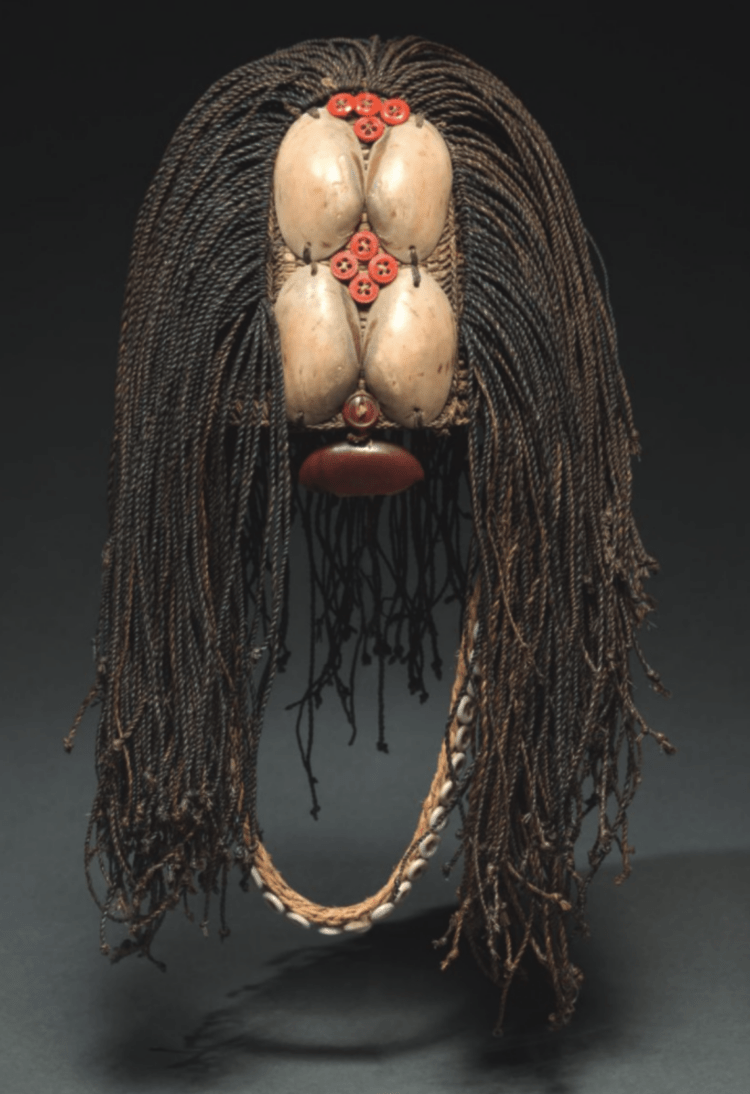

In “Manʼs Hat (Sawamazembe),” from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DCR), gender fluidity is evident in the emulation of a womanʼs hairstyle, yet this piece symbolizes high status for a man in society. This piece not only symbolizes masculine strength, but also respect for women and their inherent strength. Through the collection of various sculptural forms, beauty and ugliness are celebrated. Furthering the curatorial narrative, “Nkisi Nkondi” statues from the DCR populate the end of the gallery. These sculptures, known as power figures, are largely presumed female and known for the metal spikes they bear. They hold cavities that carry traditional medicines or seeds — these cavities, protected by glass, are meant to serve as the “other world.”

Concluding the exhibit with these figures reminds us of the strength inherent in the “Nkisi,” but also in the signage, the treatment of these objects as “fetish images” in European and Western cultures resurfaces. Private collections and loans from white-dominated institutions largely comprise the array of work seen. Themes of colonization are hence inescapable and essential to visitorsʼ experience.

In leaving unknown artistsʼ names blank rather than ascribing a title such as “Unknown Artist,” the curatorsʼ text leaves a trail in the narrative and contributes to a feeling of namelessness. While the text functioned to be informative and did not detract from the exhibit, we do expect room for improvement.

The inclusion of so many narratives and locations increased the complexity in handling issues of colonization. While we can appreciate the language of beauty as presented, the exhibitionʼs reliance on private collections as credits within the texts remains questionable, if not problematic. n

Part of the narrative of the unknown artists felt lost; the show is nevertheless partially lacking in representation of the very voices it seeks to promote. Still, it presents an exceptional survey of an expansive body of African art. From my critical lens as an artist, the show provided ample opportunity for thought, cultural education, and immersion in the beauty of African art.