Patterns in pandemic viewing have started to arise. People are spending significantly more time at home watching TV and movies, and young adults are returning to familiar and comforting franchises of their younger days. Think “Harry Potter,” “The Hunger Games,” and … A certain saga with a constant cover of clouds, rain, and sparkly vampires.

Yes, today we’re talking about “Twilight.”

Regardless of the over-the-top fantasy elements of the saga, “Twilight” fans have been the subject of ridicule and vitriol for a long time, and we seem to have forgotten how bad it once was. I’ve personally hidden the fact that I liked the franchise from even my closest friends, and only during the pandemic did we realize that we all enjoy the films. So what is it about this film franchise that gets people so worked up to the point that they forced others to hide their liking of it?

Well, the answer here seems to be, like many other things, misogyny.

Although a major portion of the people ridiculing teenage girls for liking a series marketed towards them were men, there was also a large group of women who chose to separate themselves from liking such a “girly” piece of media. People started attacking the series from all sides, saying that Bella Swan is a bad role model for teenage girls, that she should have been stronger, and less obsessed with her boyfriend.

Those sentiments weren’t untrue, but they also highlighted something about our response to so-called “girly” media. These criticisms inadvertently exposed the expectations of male vs. female-oriented media and characters. Especially when you look at the other main male character, Jacob Black. He continuously manipulated Bella for his own benefit, and no one batted an eye.

Melissa Rosenberg, the screenwriter for the Twilight movies made these comments about it in an interview with Indiewire in 2012:

“When you start to read the criticism of ‘Twilight,’ it’s just vitriol. It’s intense, the contempt, from critics both men and women … We’ve seen more than our fair share of bad action movies, bad action movies geared towards men or 13-year-old boys. And you know, the reviews are like ‘okay, that was crappy but it was a fun ride’… But no one says ‘Oh my god. If you go see that movie you’re a complete fucking idiot.’ And that’s the tone … with which people attack ‘Twilight’.”

Her last line brings up a universal point in the media: “It is also because it is female, it’s worthy of contempt. Because it feels female, it is less than.”

Women are made to feel ridiculous for liking something that was A.) marketed directly towards them, and B.) made because a bored Mormon housewife in Utah fantasized about a life where she fulfilled the ideals society expected of her. However, once it comes from a woman who has taken control of that idea and is able to make money off it, people don’t like it as much.

And then there’s the comparison of fanbase treatment with female and male-oriented franchises. For example, one could argue that the “Fast & Furious” franchise is fantasy, seeing as the characters in the series started as lowly street racers and have transcended to fighting terrorists and working with the government. Yet, you never see anyone en masse criticizing how unbelievable the plots are, or accusing the characters of being poor male models, with men fondling women in almost every movie and displaying other destructive forms of toxic masculinity.

Looking back at the evolution of the “Twilight” franchise, the concerns surrounding it has shifted in the past 10 years. When it first came out it was more of a role model concern — that Bella wasn’t a strong enough female role model for its young audience. Now it has shifted to ideas of consent, why the Cullens were written as high school characters when they have much more life experience than actual high schoolers, and how the series portrays people of color. With its damaging portrayal of Native Americans, the age gap between the two main characters, and the recent discovery that Stephanie Meyer stopped the “Twilight” director Catherine Hardwicke from casting a more diverse Cullen family, the saga has its flaws.

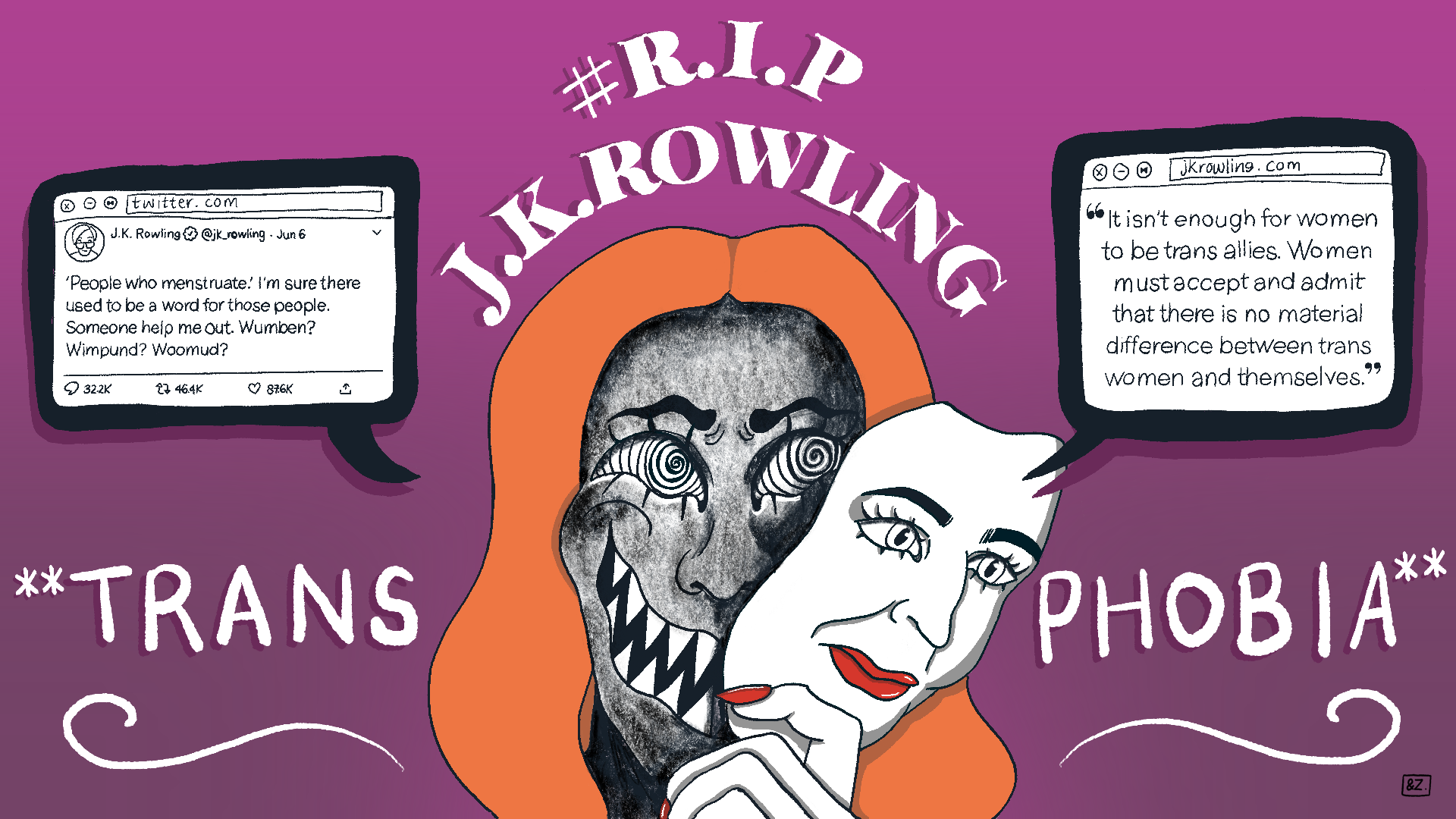

Similar concerns have arisen with the “Harry Potter” series, which has also seen a surge in popularity in quarantine — and a backlash, since the #RIPJKRowling campaign. For both “Twilight” and “Harry Potter,” it seems like its fans are separating the art from the authors, watching both series and criticizing it where the author was genuinely wrong, and shifting the blame away from the fans. Although it was never unacceptable to like “Harry Potter,” both seminal fantasy series have undergone a culture shift that leans towards enjoying the stories while still watching them with a critical eye.

So, how did “Twilight” go from one of the most hated pieces of media to having a cultural resurgence in such an unprecedented time?

The simple answer seems to be that with more time on our hands, we’ve been rewatching media that brought us a lot of excitement and joy when it first came out and now has a sense of normalcy attached to it. But I’d like to think that the resurgence of sagas like “Twilight” are because it’s becoming less objectionable to be a superfan of something, specifically something so female.

It seems like we have started to move past society’s intense hatred for female fandoms … at least in this case.