Introducing the Divestment Series, F Newsmagazine’s new series on fossil fuels, finances, and the AIC endowment.

I was at Middlebury College in 2013 at the dawn of the divestment movement. Students had learned that Middlebury’s endowment relied on funds derived from oil industry investments, and, particularly at an institution so keen on celebrating its carbon neutrality efforts, this could not be tolerated. Students marched, occupied, and otherwise demonstrated, hoping their indignation would force administrators’ hands. I was cynical. I felt sure that administrators saw the actions of undergraduates as, well, exactly that: youthful rage in need of a target, for the moment directed at a pair of old favorites, gas companies and campus higher-ups.

Then, six years later, a post-Christmas miracle. On January 29, 2019, Middlebury’s Board of Trustees voted unanimously to fully disentangle its endowment from fossil fuel companies within 15 years. An announcement attributed the change of heart to “the profound threat of climate change.” Though, as the Chronicle of Higher Education reported in August, the move likely had as much to do with fossil fuel companies’ sinking profitability as with an injection of moral rectitude.

Whatever the cause, divestment from fossil fuels happened at Middlebury, and it’s happening elsewhere, too. More than a thousand institutions have divested funds from fossil fuel companies — 15% of which are educational institutions. If you type “Chicago” into the divestment database’s search bar, you get two results: Chicago Medical Society and the Field Museum. No School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC).

The finances of both SAIC and the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) are managed as one entity. Audited financial statements for each fiscal year are freely available online. Looking them over, I learned the total value of the Art Institute of Chicago’s assets — a little over $1.6 billion. Alexandra Holt, the AIC’s executive vice president for finance and administration, told me that SAIC’s share of the endowment is around $240 million. When I asked, Ms. Holt told me that number includes “a small amount of energy assets.”

She sent me the Official AIC Divestment Policy, adopted in 2013. The policy contends that the AIC’s job is to educate, not intervene in political matters: “The Art Institute maintains a strong presumption against divestment for social, moral, or political reasons.” Divestment will only occur if a strong case can be made that continued investment in a particular sector threatens the AIC’s ability to educate creatives.

If you Google “SAIC divestment fossil fuel,” one of the top results is a gofossilfree.org petition started by Francesca Dana at least five years ago, calling on then-president Walter Massey to “develop a plan to divest within five years from direct ownership and from any commingled funds that include fossil fuel public equities and corporate bonds.” The 99th signature came from Catherine C., two years ago. Compelled both by the roundness of 100 and the possibility that entering triple-digits would bolster the petition’s status, I signed it.

Nothing happened. Walter Massey is no longer president, Francesca Dana has graduated, and SAIC has taken a firm stance against divestment. Whatever movement SAIC once had has fizzled.

Is Divestment Good?

It seems intuitive that taking money away from fossil fuel giants would hurt them. But really, it depends on the kind of pain you’re expecting to inflict. If you’re hoping for immediate damage to their share prices, dream on: One institution’s divestment is another institution’s (or individual’s) opportunity. Investors unconcerned with their investments’ ethical values will jump at the opportunity to occupy vacated space.

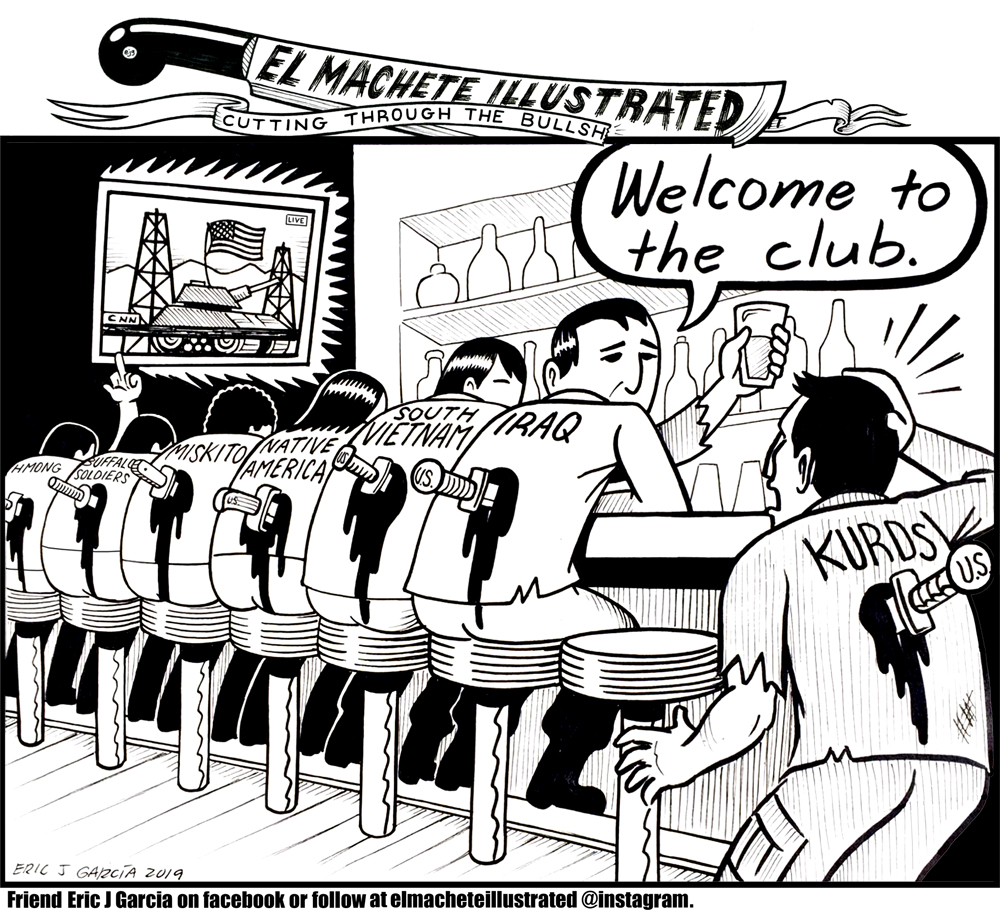

For evidence, look at the apartheid divestment campaign, which started in the 1960s and gained steam in the 1980s. Eventually, about 150 U.S. educational institutions pulled investments from companies doing business in South Africa. One study found that the movement meant relatively little for the companies’ share prices: “The boycott primarily reallocated shares and operations from ‘socially responsible’ to more indifferent investors and countries,” reported the New Yorker.

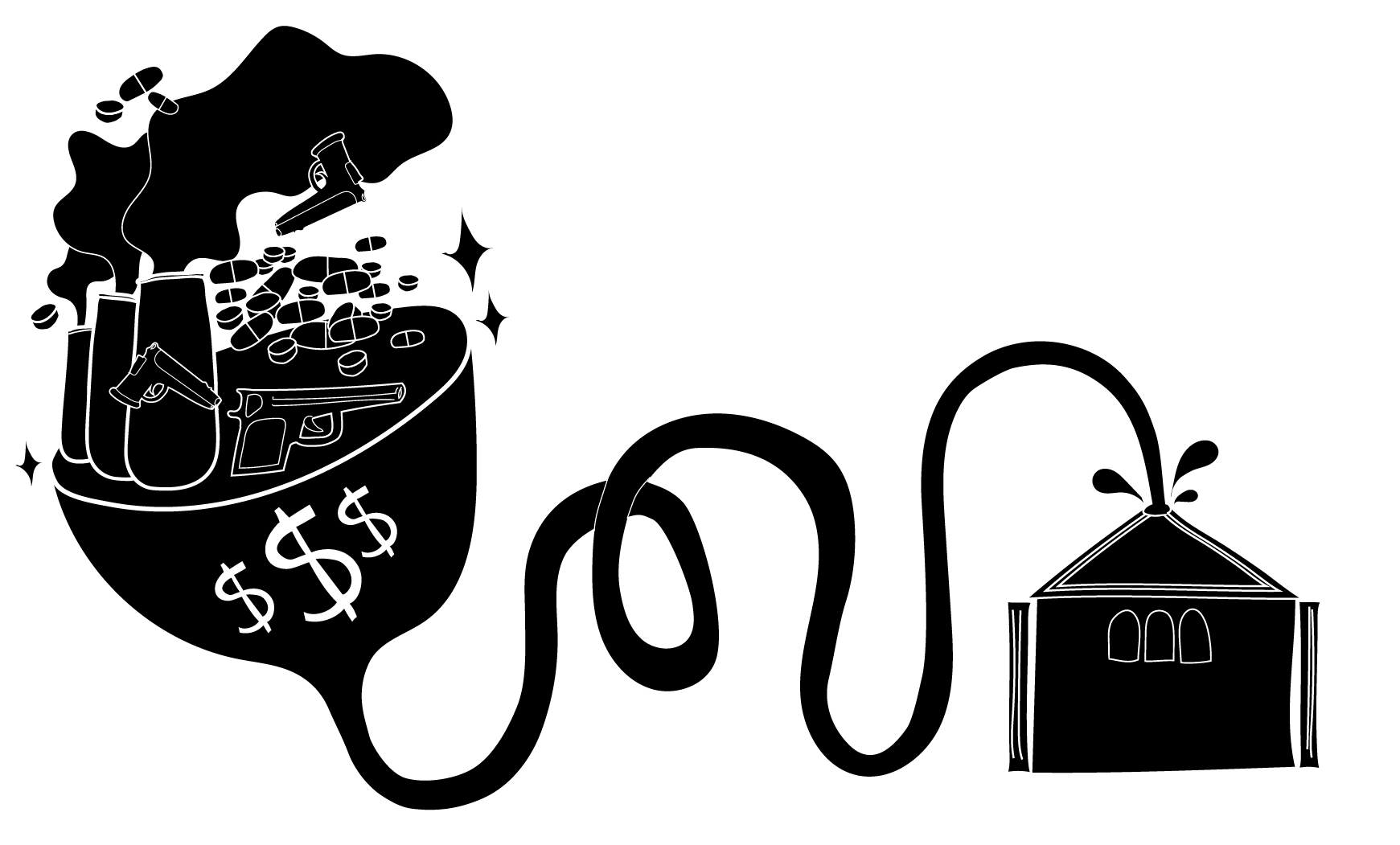

Additionally, “sin stocks” — commodities like alcohol, tobacco, gambling, and/or defense — consistently outperform the market. Essentially, this means guns and booze stocks grow at a faster rate than the market as a whole. For example, the Barrier Fund (formerly the Vice Fund), a prominent “sin-vestor” which exclusively invests in sin stocks, “has beaten the S&P 500 by an average of nearly two percentage points per year since 2002.” In other words, when the whole market is up 10 points, sin stocks are up 12 points. Sin, generally, is big business.

So, if sin wins, and if there’s relatively little correlation between divestment and companies’ share prices, why divest?

Ideally, divestment catalyzes a cultural shift. High-profile divestments help stigmatize malignant sectors, spotlight social/political movements, and encourage other high-net-worth people and organizations to follow suit. Divesting funds from fossil fuel companies may not deal their shares a fatal blow, but it may well spark broader change.

In the case of divestment, it has. On September 10, 2018, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and London Mayor Sadiq Khan co-authored an op-ed in The Guardian in which they pledged to fully divest their cities’ public pension funds from the fossil fuel industry, and called on “all cities” to do the same. Two days later, California Governor Jerry Brown issued an executive order committing California to 100 percent use of zero carbon electricity by 2045. In a recent appearance on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” presidential candidate Joe Biden declared climate change the single most urgent issue the country faces today. This is the cultural shift activists hope to effect: foregrounding climate change in the broader political discourse.

How SAIC Fits In

The climate is changing, and our students care. In a politics survey conducted by F Newsmagazine last year, climate change was the issue most frequently mentioned when students were asked about their major concerns. On September 20, thousands of people marched in the Global Climate Strike, many of them students.

“SAIC is committed to becoming carbon-neutral,” Tom Buechele, Vice President for Campus Operations, told me via email. “Even though our campus footprint has expanded by more than 232,000 gross square feet since 2009, we have reduced our carbon footprint by 57%. Last year, we were 67% carbon neutral.” According to a recent announcement from President Elissa Tenny, as of Jan. 1, 2020, “SAIC will be 100 percent carbon neutral.”

These are significant steps forward in a world where the need for progress is beyond urgent. SAIC deserves praise for these sustainability initiatives. But the fact that the Art Institute of Chicago’s vast investment portfolio includes fossil fuel means that SAIC relies in part on its industrial health. One must wonder: How does the impact of campus carbon neutrality measure up against the impact of fossil fuel investments?

There’s more work to be done in determining the causal link between fossil fuel investment and the effects of climate change. We also must evaluate the financial benefits of these investments — if proven to produce unreliable returns, the motives behind the investment would be called into question. Ultimately, we climate-concerned students deserve to know about the extent to which our tuition dollars are contributing to the planet’s degradation.