Kevin Coval is a Chicago-based poet and activist who has been deeply involved with nonprofit educational organization Young Chicago Authors (YCA) since 1999. Among his literary projects is “BreakBeat Poets,” a book that he co-edited with fellow poets Quraysh Ali Lansana and Nate Marshall, featuring poems by 78 poets that articulate the legacy of poetry in hip hop music and culture. In 2001, Coval and poet Anna West co-founded Louder Than a Bomb, the largest youth poetry festival in the world, giving over 1,000 young poets from the Chicago area the opportunity to compete both as teams and individually.

In September, Coval and illustrator Langston Allston published a graphic poetry book titled “Everything Must Go,” in which he touches on the history of Wicker Park as a community for working-class Chicagoans, immigrant families, and fledgling artists, emphasizing how much the neighborhood has changed since the 1990s. The book puts words and a sentimental narrative to the imagery and process of gentrification, deepening understanding of how a thriving arts community changes the landscape of a neighborhood, and what elements we, as artists and art consumers, should be aware of when we touch these spaces.

In your poem, “New Construction,” you compare the architecture of the old Chicago two-flat to the ultimate development of, as you call them, “viagra condos.” I’m wondering if you can expand on how you witnessed the two-flat serve the community and how drastically this newer architecture altered the physical and social landscape of Wicker Park.

Yeah, so my dad has a two-flat — I’ve lived in it, he has renters, families move in and out of it. We’ve had a lot of housing instability in our family, but it’s a space that has helped serve, insure, and build communities of families. With the viagra condos, it’s really about the core and the materials that are thrown in a really rapid manner. We don’t build new buildings with that same kind of care, and I think that this is itself a metaphor for not caring about the people who live in them — and we certainly don’t care about the people that we’re displacing with these new buildings, either.

I’m personally very touched by “Ode to the Waitress,” very specifically the line “mood wed to income,” though in this poem you acknowledge that many of these low-wage workers do a service to the community that has immense emotional weight and is thus pretty immeasurable. There’s this sense of erasure of working class contributions to communities that are developing in the way that Wicker Park has. Can you speak a bit about the value that the working class brings to not just Wicker Park, but every American neighborhood?

Yes, and first of all, I definitely agree with this and I think you said it beautifully. While we’re talking right now, I’m on my way to Louisville, Kentucky to support my buddy’s book release, on the road with my longtime homie Mariah, and we just stopped in [a small town] like Lebanon, Indiana, or something like that. The woman who brought us our salads couldn’t have been nicer, even though both of us have all kinds of weird dietary restrictions. I think that to get us through the day, it’s the people who work often for minimum — maybe a livable wage — that make our lives palatable. That makes our bodies and our time in cities habitable. If the future of cities is without working people or without a working-class, then what kind of city are we living in? The people’s labor and the character of the people is what makes the city attract money and different sectors of the economy, which then ultimately seek to erase working people from the space. And also, like you’re saying, the contribution of working people to the integrity, the character, and the development of that community.

Would you say that in Wicker Park, specifically, that this process has been more pronounced in recent years?

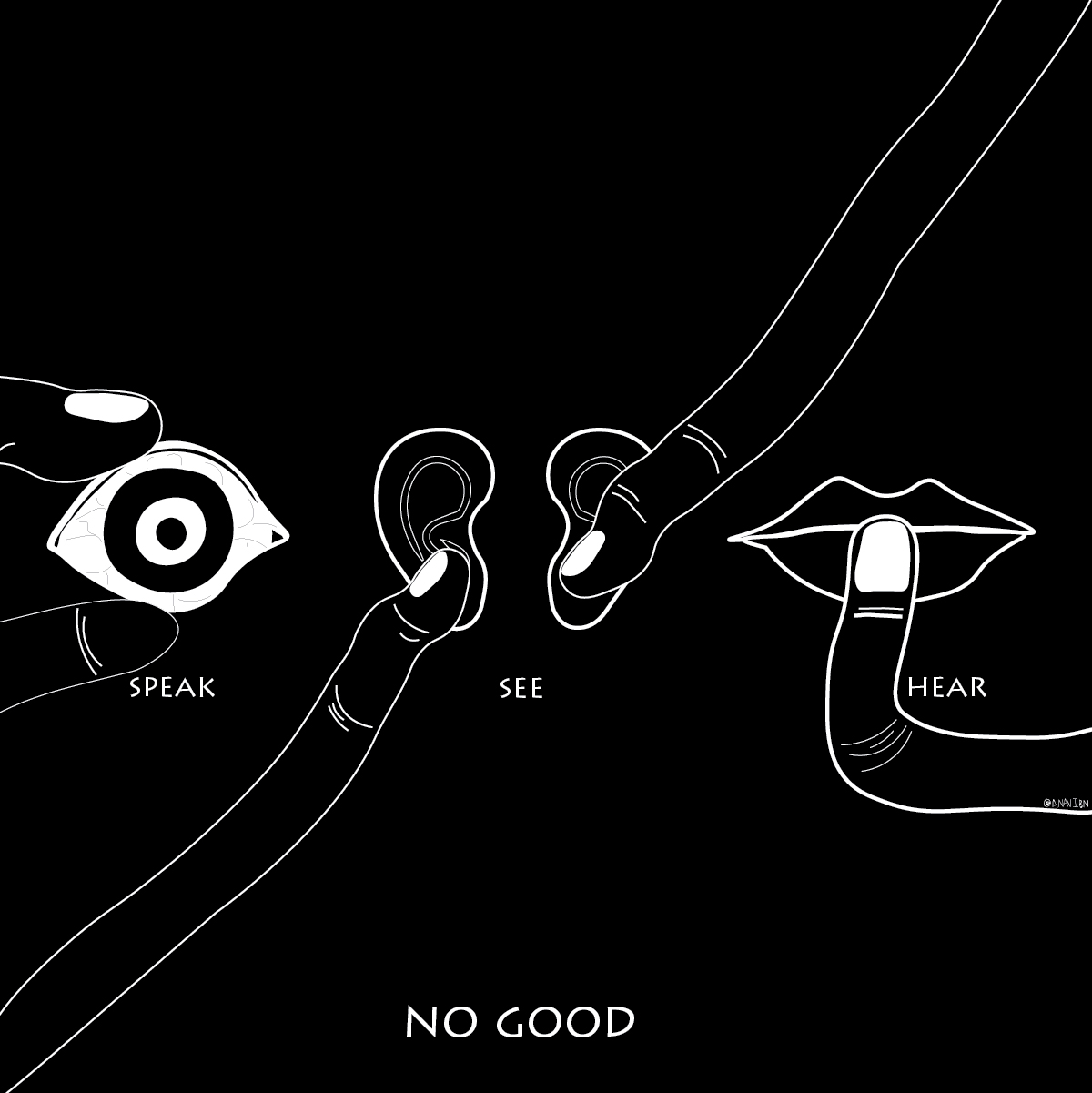

Well, this process of gentrification is not new. I remember hearing about the term at some point during the late 90s, but there’s always been this process of removal and displacement of working people. Certainly the erasure of people from a land is also a part of this country’s history and in any process of colonization. There are aspects of erasure that have a lot to do with white amnesia; when it comes to history, a deliberate forgetting, or a deliberate unremembering of a space, or of a land. This is in part because we oftentimes don’t want to look at the truth of a space, or a land, or a people, because it’s sometimes a hard truth to look at.

I think in Wicker, when I was a young person moving into the space, myself and the people who moved in around me and after me were all part of a plan of displacement as well — of the working class, Latinx, and Ukrainian and Polish folks who were there when I got there. It was just a different part of the process and a different cog in a larger system that has everything to do with the history of global economics. In some ways, it fits in a particularly devastating post-industrial moment. Certainly, when I moved into Wicker, it was the working class that I mentioned earlier, but I was able to move into a space that was filled with working artists who moved there because they could afford the rent, to try to carve out a dream for themselves around this idea of being an artist, or a writer. I certainly had never allowed myself to have this dream before. In that moment, it was people who were experimenting with their lives, trying to do something different than what they had seen prior. There was a real power and beauty in that — but our presence in that space was also about a displacement.

Yes, and that relates directly to this next question about the final poem in the book, and its namesake, “Everything Must Go,” in which you suggest that the Wicker Park that you knew provided a place for artists to make both accomplishments and mistakes, to develop and expand. Do you see YCA as an effort to cultivate a similar space for fledgling artists of this younger generation?

Yeah, I would say that all of us need community and spaces where we can go and have others see us. I think that’s a desire that all people have, and I certainly think it’s part of what happens at YCA. A lot of what YCA is — aesthetically and also spiritually — comes from our time as young artists in the city. Wicker, house, and hip-hop communities [are examples] of spaces that we try to cultivate and hold for younger artists who might not yet have committed themselves to practicing art. It’s a big thing to commit to! Sometimes, we’re the first space for young people to allow themselves to have that dream.

Are you witnessing the surrounding, gentrified environment of Wicker Park limiting the potential of these artists to grow and expand? If so, how is YCA challenging this?

Well, we’re still in the neighborhood because we have a great landlord; we’ve been here for about 25 years. I think that all of these spaces that are encouraging and allowing young people to gather are really important to the city, especially a city like Chicago in which space itself is policed by the long arm of institutional racism. YCA is a space where young people can build with one another and be themselves in their own youth cultural practice, which is really important because these spaces are few and far between.

We happen to remain in Wicker because of many reasons — in part, because we’re at a good nexus of multiple public transit lines. But we need spaces like ours around the city. There needs to be space in every neighborhood of Chicago where young people feel safe going, not just in terms of their body but also in terms of how the space allows them to express themselves; to not tell them to be quiet, to not tell them ridiculous shit, like “pull up your pants,” or “don’t use that language,” or whatever. What happens if we build a space where young people can come together and be themselves? I’ve always found that those are the freshest, most engaged, interesting, and vibrant spaces that we have access to. For me, that’s the move.