Around the age of five, my dad began to take me on trips to our local public library. Every day consisted of me coming to terms with a learning disability, while my dad would be happy to just see me encased in a sea of tomes. Even if I wasn’t reading any text, the pictures would suffice. He discouraged bookstores. Those institutions became another capitalist arm that made it harder to access something which he considered should be free: Literature. “Free” meant inclusivity to immigrants like my father — the ones who had to pay for everything. And a moment of silence and joy that he could bring to his child were not line items allocated for his taxes.

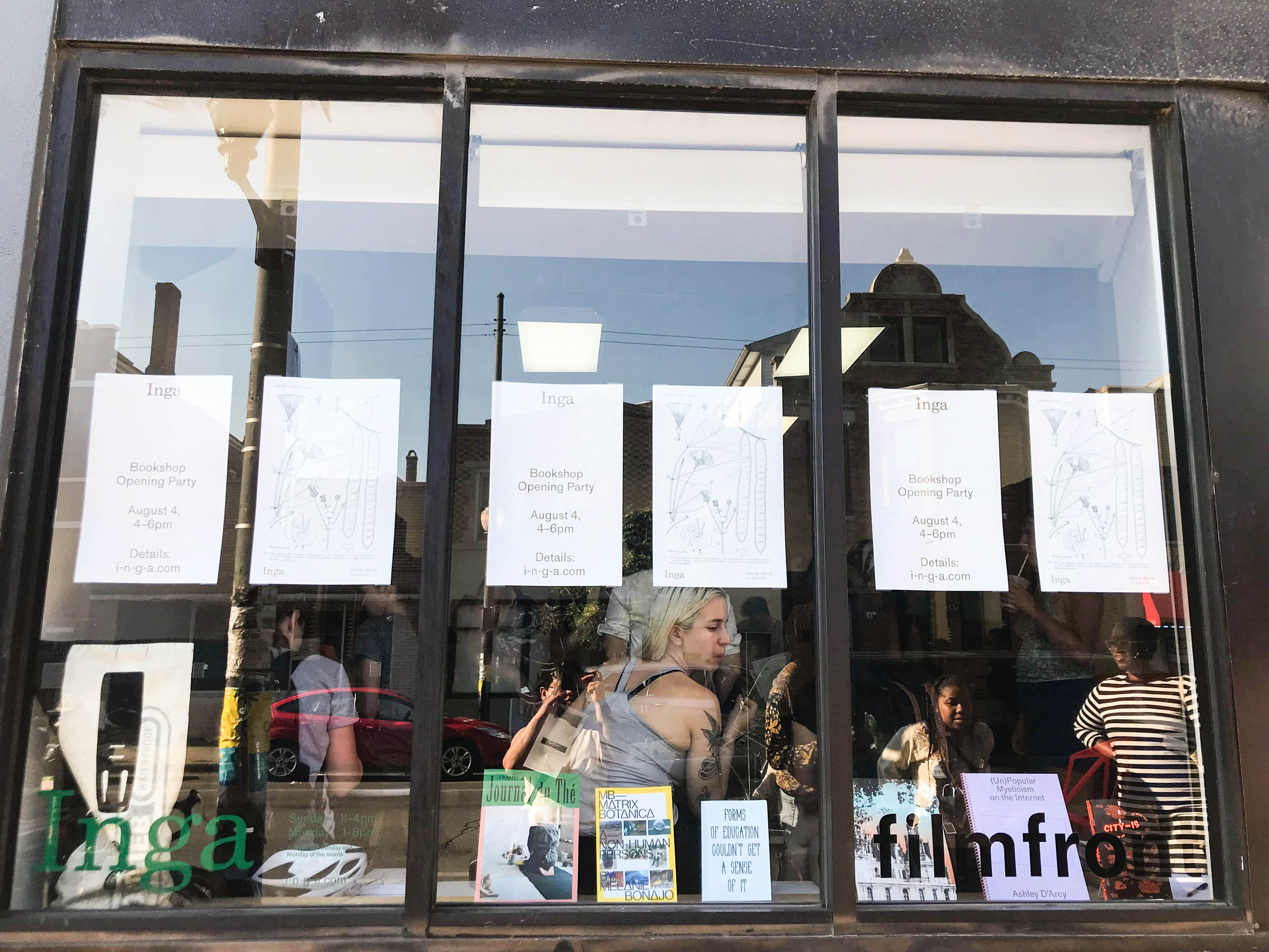

It was with this same skepticism in mind that I walked into the grand opening of Inga Bookshop, a new bookstore right on Pilsen’s 18th street stretch. I could tell the shop was at capacity with attendance. There was an obnoxious number of “excuse me”’s as I tried to fold through the sea of canvas tote bags. I was happy to see a fair mixture of readers of color once I waded the waters. I was also happy to see my friend and Chicago poet Imani Elizabeth Jackson getting ready to perform some of their poetry in the bookshop’s backyard space. They traversed the volumes and readers with ethereal grace, accentuated by the color green: Green garment, green peas, green flecks of color skittering across their irises. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t enchanted by the homemade ice cream that Imani provided for the opening. It was a surprise to have my lips tingle from the sensuality of cherry and pepper ice cream along with ginger sorbet.

It didn’t take long for me to count the number of attendees I recognized. These were old classmates, colleagues, friends, all somehow connected to the art world. I witnessed a majority of them interact with the materials laid out around the bookshop, peek around to see who they recognized in the crowd, and put down the publication shortly afterward. It was the same vibe that I’ve picked up on when I attend exhibition opening receptions. The community that was not in attendance were the Pilsen residents who had made 18th street their home generations before most of the attendees were born. The families who passed the shop looked inside, curious but confused. I wanted to say that these books were made for them, but I knew that would be a lie.

The selection of books didn’t resemble the titles I grew up with. Authors’ names were devoid of accents, diacritics, and heavy inflections. The shop itself had the same makings of a pop-up in Brooklyn — temporary and constructed in a way where materials could be quickly stored. Barely any air conditioning and a group of people turning papers into fans were what transported me back to the New York Art Book Fair.

As I browsed the stacks, I continued to experience a recurring sensation of vinegar in my soft palate. I couldn’t help but think, “These are the kinds of texts I would find at SAIC,” and that was it. These were titles that focused on a certain audience that had a familiarity with arts and culture. So much so that it didn’t present itself as open for the community it was inhabiting. I wondered why this space, why now, and who it was for.

My fears were confirmed when I looked behind the counter to see who was in charge: a small circle of mostly white owners. I asked them if this space was now a permanent staple in the community. The owner looked apprehensive. They informed me of how Inga is open two days out of the week (Sundays from 11 am – 4 pm and Mondays from 1 – 8 pm) and the rest of the week, space is known as Filmfront: a “cine-club located in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. selected programs draw from overlapping spheres of global, classic, documentary, experimental and local cinema. situated at the core of a diverse community, our storefront venue invites a cross-cultural dialogue in the form of discussions, panels, lectures, and exhibitions in addition to our regular screenings.” I hadn’t realized that their “diverse community” would be so interested in a storefront that confounds the local and the global in the same breath.

My gut reaction was negative. The pieces kept adding up against Inga and in favor of my initial suspicion of gentrification. Here is a book shop, sitting on one of the most gentrified streets in the Pilsen community, with a majority of white owners and inconsistent hours, set to promote “self-published and independently distributed titles on art, design, film, and theory.” As I took in the sights of Inga, my imagination swayed in the direction of what space would look like on Tuesday. Do the books just become stored for five days, being encased in comfortable darkness of the back room?

With a cue from one of the white organizers, everyone in the store was encouraged to move to the backyard space; Imani’s performance was about to begin.

Through the alley, a mass exodus came upon a small patch of backyard grass. The guests sat in a circle with Imani resting at one end with a bowl of green peas and papers, ready to perform. The white organizer gave a small speech detailing her gratitude for Imani’s work and the number of attendees who made the house packed on opening night. As Imani read from their piece written for the occasion, they consumed from the bowl of peas and passed it around the circle. As I ate from this participatory nutrition, I thought about the concepts of family, generational wisdom, and self-sustainability, all themes in Imani’s poetry. With each dropping off a page, I felt Imani reach a deeper level of unearthing the generations that come before them, resting on the simplest form of the pea.

As the performance wrapped up, and the attendees went on their way out, I looked into the storefront from the outside. Peering in, you could see the number of attendance swell once again. This place did not feel like it was designed for me, or the people I live around. No one asked for this. And I could slowly feel myself turning into my father, with an anti-bookstore sentiment ringing loud. How many months will it take for this establishment to have a similarly gentrifying neighbor? The ripple effect of shifting real estate is a legitimate problem. Maybe invest the space back into the original community members and allow them to do with it as they please. Too often, these temporary projects will insert themselves into communities, do their business, and leave, rarely trying to reach out to the surrounding community. If this trend continues, Pilsen and other communities of color will continue to be seen as zones for temporary splurges, instead of rich cultural hubs. Instead of coming to Inga, I’ll most likely be spending my Sunday afternoons in the Rudy Lozano Branch of Chicago Public Library, only a few blocks down.