“We cling to memories as if they define us,” Dr. Ouelet tells Major Mira Killian, “but they don’t.”

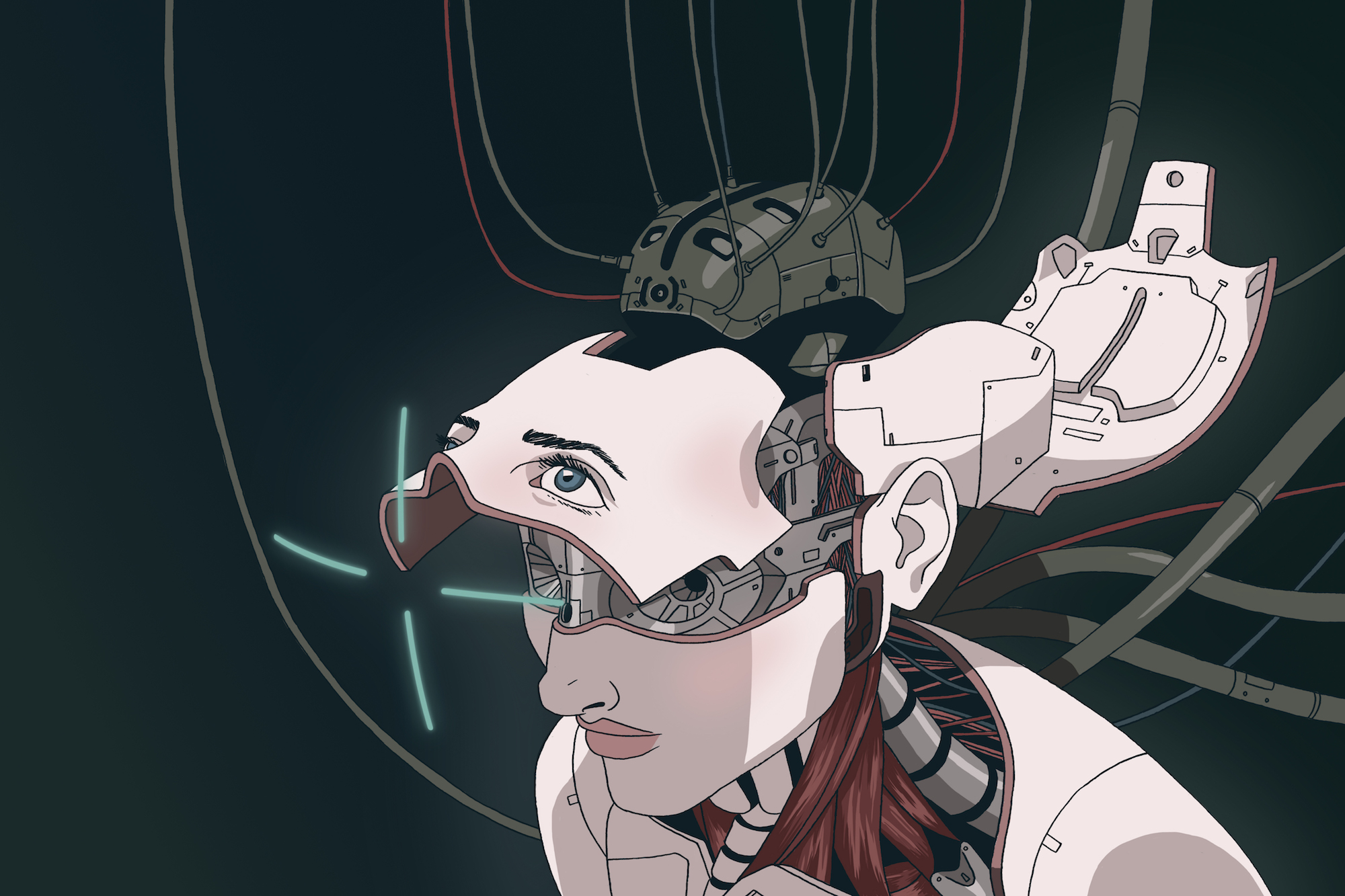

Twenty-seven years after the legendary anime masterpiece “Ghost in the Shell” transformed science fiction, its long-anticipated live-action adaptation was scheduled for release. The anime, based on the manga of the same name, tells the story of Major Motoko Kusanagi, a cybernetic supercop with a human brain, as she tries to unmask a terrorist hacker who is offing government officials in Japan’s “New Port City.” The live-action adaptation stars Scarlett Johansson as “Major” and Michael Pitt as the elusive cyber-terrorist, with Rupert Sanders (“Snow White and The Huntsman”) directing a script by Jamie Moss, William Wheeler, and Ehren Kruger.

What do Johansson, Pitt, Sanders, Moss, Wheeler, and Kruger all have in common? They’re all whiter than Tilda Swinton’s bald head.

When asked about how her role in “Ghost in the Shell” might be the latest example of Hollywood whitewashing Asian characters, Johansson responded:

“I certainly would never presume to play another race of a person. Diversity is important in Hollywood, and I would never want to feel like I was playing a character that was offensive.”

The trouble, of course, is that she already has “presumed to play another race of a person” and that it is “offensive,” regardless of what she would or would not “want to feel.”

Sanders unsurprisingly claims that the white Hollywood megastar just happened to be “the actress [he] felt was best in the role.” Given that Johansson was his “first choice” and that he was “honored” that she took the part, it is unclear whether any auditions happened at all.

Did Sanders really think he could he really get away with referring to Johansson as “Major Motoko Kusanagi”? Well, apparently the Major’s race wasn’t the only thing Sanders felt needed adjusting. To dodge any inevitable awkwardness, our ghost-white robot uber-woman would now be named “Major Mira Killian.”

I truly wish it ended there.

Despite wanting to boycott the most racist product of pop-media whitewashing in weeks (here’s looking at you, Danny Bland), I felt that if I was going to write a critique of “Ghost in the Shell” I should probably go see the thing. I have to say, I’m glad I did, because it truly changed my perspective on the film.

It was even more racist than I could have possibly imagined.

[Spoiler alert for anyone who still wants to waste $15 and two hours of their ever-shortening life.]In the original, Major contemplates her life before her cybernetic augmentation. Are her memories truly her own? Or, could artificial intelligence create its own memories? Its own identity? Its own “ghost”?

In the adaptation, Major actually does some detective work. After discovering that her memories have been implanted by her creator, she works to uncover the true details of her former life. Let me skip some bad storytelling and save you a few bucks. (You might want to take a seat.)

Major’s human brain was stolen from a Japanese runaway named Motoko Kusanagi. Yes: Scarlett Johansson used to be Asian.

While “Doctor Strange” and “Iron Fist” infamously missed opportunities to rewrite Orientalist source material, “Ghost in the Shell” not only erases an Asian character and replaces her with a white one; by weaving that erasure into the narrative, it wears its racism on the sleeve of its transparent thermoptic jumpsuit.

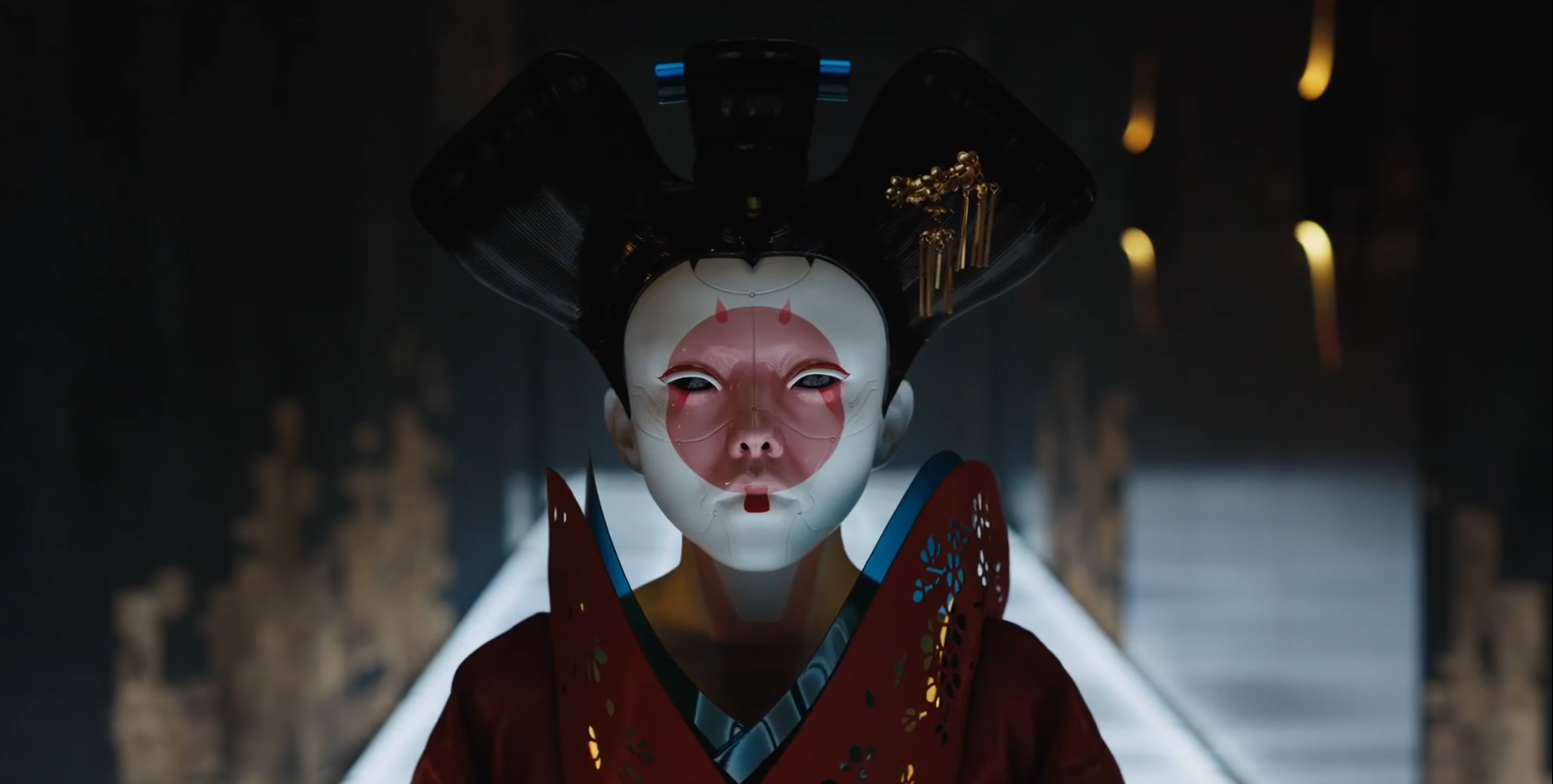

Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) actors certainly do appear in the film, but nearly all of them are there to be killed by our newly-white heroes. Chin Han plays Togusa, whose role has been drastically reduced for the remake. Takeshi Kitano has an important role as Aramaki, but he speaks exclusively in Japanese for no discernable reason. (As Keiko Agena asked, if everyone in the film understands Japanese, why on earth is he the only one speaking it?) Fans of “Wolverine” and “Arrow” were excited by the announcement that Rila Fukushima would be joining the live-action cast, but they would be hard-pressed to find her in the film. She was the face model for an army of geisha robots, which were added for the remake.

The argument goes that white leads do better at the box office, but this is untrue. And, as Traci Kato-Kiriyama has said, if all of this was really about making money, the studios would cast an Asian actress and sell the film to China. As it turns out, “Ghost in the Shell” did worse than “Boss Baby” in its opening weekend and Paramount was forced to admit that their casting was to blame.

Hollywood whitewashing is not new, but that’s precisely the problem. AAPI have been boxed out of leading roles since Mickey Rooney was just a shimmery white twinkle in the whites of his white father’s eye. Without the box office myth to fall back on, what is left to explain the lack of AAPI representation in Hollywood?

The answer is what it always has been: colonialist racism.

Whitewashing is a pop-media extension of the colonialist project, which aims to erase people of color while stealing their culture. “Ghost in the Shell” actually writes the colonialist narrative into its plot: Motoko’s body is colonized (by invasive white scientists), appropriated (for the purposes of a cybernetic experiment), and repackaged (in a new “shell”) to fit the white ideal.

We see traces of the colonialist project throughout the film. While the original anime referred to its landscape as “New Port City,” the adaptations sees Japan as a nameless metropolis decorated with Japanese signifiers: robot geisha (the ultimate western fantasy of foreign culture without humanity), hologramic koi, and a gritty neon underbelly more reminiscent of “Blade Runner” Los Angeles than real-world Tokyo. “Ghost in the Shell” allows its white tourists to play Robocop in a Disneyland Japan without ever having to confront the actual people from which it’s stealing. (Except, of course, to put a bullet through them.)

Comparing this effort to white supremacy and Nazism might not be as extreme as it sounds. Erasing Major Kusanaga’s Japanese body to make way for a white one is a clear case of cyber-eugenics, which posits even artificially-created white bodies as superior to nonwhite ones. White bodies aren’t just the ideal, they are the norm from which all other bodies deviate. The impact of this erasure extends far beyond the screen.

The United States has a long history of AAPI oppression. The American government relocated and interned 120,000 Japanese and Japanese-American people between 1942 and 1946, but it doesn’t end there. Today, anti-AAPI hate crimes are on the rise at exponential rates (including one on March 30 in Cleveland, another on April 6 in Atlanta, and the United Airlines assault on April 10 in Chicago). These crimes are often underreported, and when they are reported, they’re frequently logged as generic offenses and consequently “don’t show up in national data about hate crimes.” In these cases, not only are AAPI being erased, the erasure itself is being erased.

Film and television can go a long way toward combating these statistics. Recent studies have indicated that onscreen representation actually influences the self-esteem of POC viewers.

Nicole Martins of Indiana University wrote about “the idea that if you don’t see people like you in the media you consume, you must somehow be unimportant.”

The frightening thing is, we’ve known this. In 1976, George Gerbner and Larry Gross wrote a paper called “Living with Television,” in which they explained, “Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation.” It is vital to remember that this annihilation happens not only in the minds of POC viewers, but in the minds of white viewers, as well.

Last year, AAPI actors occupied 4 percent of the speaking roles in American film, television, and digital media.

Why has it taken so long to get the message across? Part of it might have to do with the fact that of the 1,000 highest grossing films of the last year, only 3 percent were directed by AAPI — a number that has not increased at all in the past decade.

Paired with the stark rise in anti-AAPI hate crimes, “symbolic annihilation” ceases to be symbolic. Maybe “Ghost in the Shell” did not set out to annihilate AAPI, but a film doesn’t have to be white supremacist in intention to advance white supremacy in reality. And perhaps it is this accidental white supremacy that is the most insidious, because not only does it affirm extant racism, it contributes additionally to it.

When Major Killian’s creator tells her, “We cling to memories as if they define us, but they don’t,” she is echoing the mantra of white colonialism, a project that strives to forget not only its own bloody history, but the history of the people it erases. In its place, it posits false cultural approximations to decorate its victory and relishes the beauty of the dead.

bla bla bla…. jfc shutup

yeah let’s ignore the fact anime itself whitewashes e.g. blue eyes, often using eyes larger than what most asian eyes look like, the blonde lots of blonde hair with blue eyes. Let’s just ignore the fact that Japan was literally allied with Nazis during WWII, since you bring it up, as well. Good grief this piece reads so whinny and cringe. What do you expect coming from a white dude lol. World isn’t as black and white.