Twenty-eight years ago, the Joker shot Barbara Gordon in the pelvis, photographed her undressed and bleeding, and raped her. Now infamous for exploiting female trauma to catalyze male character development, Alan Moore’s legendary comic, “Batman: The Killing Joke,” is a bleak tale of abuse. Barbara Gordon, who suits up nightly as Batgirl, is often seen as a preeminent example of a “woman in a refrigerator,” and the book has rightly endured decades of criticism for her mistreatment.

So, last year, when producer Bruce Timm began work on an extended animated adaptation, he decided to “actually use that extra story length to address one of the issues that [he] kind of always had with the comic in the first place,” by adding a half-hour prologue that is “all about Barbara.”

The new adaptation, which premiered at San Diego Comic Con last weekend, had the opportunity to rewrite Barbara’s brutal fate and reestablish her as one of comics’ most complex and important female heroes. But it doesn’t.

The film begins with Barbara’s narration. “First of all, I realize this is probably not how you thought the story would start,” she says, seemingly aware of her treatment in the original telling.

Given her near-absence in Moore’s book, Barbara’s leading role in the opening gambit is reassuring — until she sets the scene in a “stunning” Gotham City “before the horror began.” In its opening seconds, the film alludes twice to the sexual violence to come, as if it is simply inevitable.

The prologue follows Barbara’s pursuit of a group of small-time thieves. Their ringleader, Paris Franz (yup), takes an immediate romantic interest in her. When his boss complains that “the Bat and his bitch” are all over the news, Franz replies, “What can I tell you? Batgirl’s hot!” Routinely calling her “baby,” “my love,” and “my special girl,” Franz commits further crimes in order to lure Barbara to him. When he drugs her to take advantage of her, Batman comes to her rescue.

Barbara and Batman argue heatedly and often about whether she should continue on the case, given Franz’s blatant harassment. She acknowledges that his relentlessness is “a trick,” but says it’s still “a little flattering,” at which point Batman actually mansplains sexual objectification.

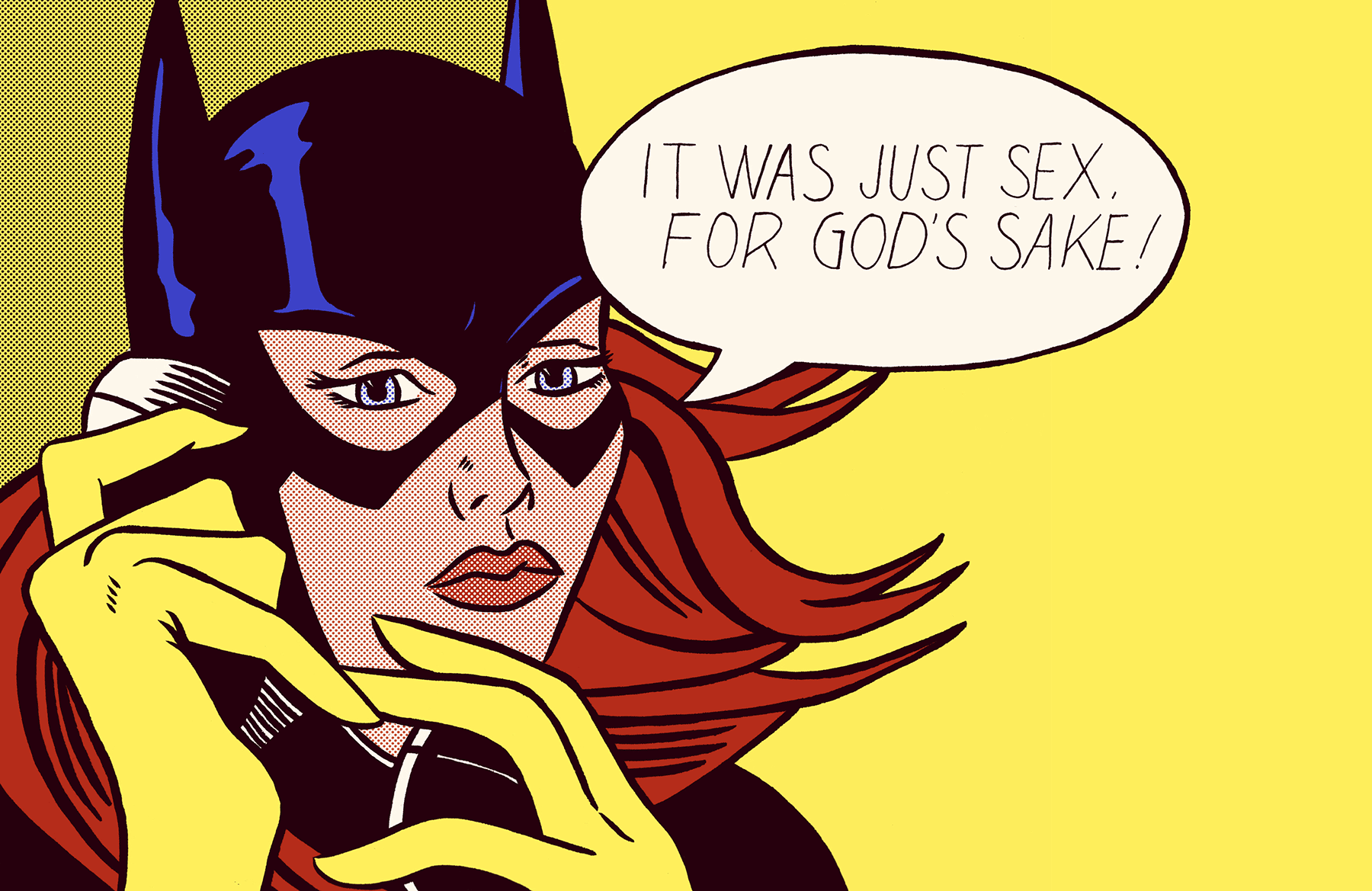

If you thought you observed romantic tension between “the Bat and his bitch,” you would, amazingly, be right. Though some stories have explored a romantic link, Batman’s role in Barbara’s life is typically that of father figure. “Batman: The Killing Joke” firmly establishes him as her love interest. In its most shocking and controversial scene, the heroes consummate their connection after brawling on a rooftop. The film gratuitously shows Barbara mounting Batman, who gropes her before she undresses on camera and descends out of frame. Batman then promptly plays the role of the aloof boyfriend. When Barbara eventually connects with him over the phone, she shouts, “It was just sex, for god’s sake! It doesn’t have to mean anything!”

Batman replies, “Later,” and hangs up.

Barbara has her chance to take revenge on Franz when she and Batman find him and his cronies at the Gotham docks. She beats Franz nearly unconscious before she sees Batman looming over her disapprovingly. Barbara looks at Franz, bloody and struggling for air, and hangs her head, disappointed in herself.

After Franz is arrested, Barbara gives up the cowl and returns her suit to Batman, saying, “I thought I’d save you the trouble of ending this.”

In the face of criticism, the film’s writer Brian Azzarello said that Barbara is “stronger than the men in her life” and that she “controls” them. Yet Barbara is constantly the object of male attention, and she consistently compromises her own interests to accommodate men. By dropping her suit at Batman’s feet, she relinquishes the most important part of her identity to him.

All of this precedes one of the most infamous scenes in comic history.

Barbara’s narration ends, and the film picks up where Moore’s book begins. The Joker has escaped from Arkham Asylum and bought an amusement park, with plans to lure Batman to his death. On the way, he stops by Barbara’s apartment, shoots a bullet through her spine, rapes her, and takes photographs to commemorate the evening.

During an argument in the prologue, Batman tells Barbara that they are “partners,” but “not equals.” He explains, “You haven’t been to the edge … [of] the abyss. The place where you don’t care anymore. Where all hope dies.” The scene implies that Barbara cannot measure up to her male counterpart until she endures the abuse and trauma to come. The film remorselessly ascribes value to sexual violence.

What makes all of this even more troubling is that the core creative team (comprised solely of men) seems oblivious. When asked to what extent they were trying to make a statement about misogyny through the character of Franz, Timm said, “It wasn’t that we were necessarily trying to make a statement about the uglier side of some males’ attitudes towards women. … It just seemed appropriate for the story.”

Remarking on Barbara’s final moment as Batgirl, director Sam Liu said that Barbara is “the one who decides, ‘I have to stop. There’s a problem here, and I need to step away from this.’ I think that comes from an emotional strength.” However, her retirement only reads as submission when she’s been manipulated and condescended to throughout the film.

At the post-premiere discussion, one journalist suggested that all of Barbara’s power seemed to come from sex, to which Azzarello replied, “Wanna say that again, pussy?”

The filmmakers must be held accountable for their choice of source material. It is not enough to say, as Timm did, “Warts and all, the story is what it is. It’s kind of a classic. … I’m just the guy who’s putting it on the screen.”

“Batman: The Killing Joke” is a sexist story. To choose to resurrect it, “warts and all,” is an artistic decision that warrants critique, as well as an implicit validation of the book’s problematic content.

Instead of depicting a brilliant, powerful Barbara, the creators show a submissive, fragile object, valued only for her sexual currency. Successfully altered, the new adaptation could have demonstrated the growth of feminist storytelling in the 28 years since the comic’s release. Instead, in trying to remedy the legacy of sexism and violence in Moore’s infamous work, Timm, Azzarello, and Liu managed to make things vastly, dangerously worse.

You’re joking right?

This is a really excellent article. Thank you for addressing what so many people willingly ignore. You’d have to be blind as a Batman-fan to not see it.