A wide-ranging conversation with performance artist, Chicago native, and Jesse Helms nemesis | Sex, politics, Martha, Dubya and Wicker Park’s Busy Bee Restaurant

“What a dump!”

I drop my paisley suitcase onto the shag carpeting and keep my arms up in the air, giving the hotel room a once-over. The room has a dirty window view of a neon sign that reads COLOR TV and AIR CONDITIONED. The king-size bed has a turquoise and aqua woven bedspread that must know semen as a spray starch. I try not to think about it. On the side of the room is a mirrored bar with a small fridge and a microwave. Above the bar is an iridescent cityscape of New York with the Twin Towers that looks like it glows in the dark.

“Oh, Martha. It’s not that bad.” George always insists everything is nice. He is such a goddamn Girl Scout at times.

“It smells.” I whiff. “For God’s sake, George, it smells like a wet dog.”

—Excerpt from George & Martha

The night before interviewing renowned performance artist Karen Finley, I stayed up late and read her new book, George and Martha. The walls of my apartment are thin, and if my laughter kept the neighbors up, it’s all Karen’s fault.

Described by writer Jerry Stahl as a “weirdly plausible bitch-slap of a book,” George and Martha has the U.S. President meeting homemaking maven Martha Stewart in a seedy hotel room for an evening of antagonism, psychotic psychoanalysis and episodes of kinky sex. The pithy dialogue between the two celebrity archetypes is liberally interspersed with images by Finley.

Emile Ferris [EF]: I enjoyed your drawings, they were such a different space from the writing and there was something genuine and connected about them that touched me. I think that was one of the really remarkable qualities of the book.

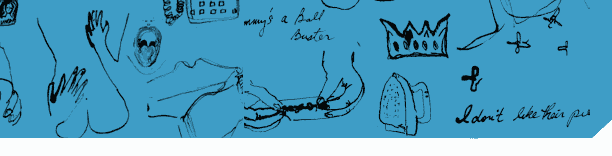

Karen Finley [KF]: Well, what I’m doing with the drawings is that I am appropriating or considering the text to be a postmodern text and also the drawings to be postmodern, and that they’re commenting or speaking about modernism…. I am considering Warhol and his drawings. He started as an illustrator, he used to draw for cookbooks, Amy Vanderbilt’s cookbooks, and he did fashion illustration, too. So, I’m taking that sensibility. It’s supposed to be Martha doing the drawings, really, like a first-person account from Martha. It’s from her point of view.

I’m also considering the New Yorker. The way I’ve done the cover art, it’s the sort of image you would see used for the cover…I used the font from the New Yorker, and also I placed the drawings within the text like the New Yorker. I’m commenting on the way that the New Yorker places images or cartoons within a text…so one could be reading a New Yorker article by Seymour Hersh writing about the horrors of Abu Ghraib, and then there’s a cartoon, or a drawing within the text. The psychotic breaks that we have within serious journalism… and how that’s been allowed and how that’s deconstructed within the format. It’s allowed so that our brain can take in the article.

EF: George and Martha collapses all these layers. Tell me about that.

KF: I’m commenting on various levels at the same time, modernism, George and Martha in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolfe?” It was 1963 when that play came out, the Kennedy era…. It was the post-war generation at that time; my generation was at its youth, at its peak, and was feeling hope for the future. This was before ’68 and before the assassinations. The Civil Rights Movement was active and there was hope that there was going to be a change in leadership. And so I’m appropriating, within a collective mindset or an audience, that play. Although I’m not really using it, I just have those same sort of characters. I start the text with the same language as Albee starts, “What a dump!” I have an imaginary child, I have the fight, so I’m commenting on it in that way as well.

EF: One of the things that was really striking to me in a literary sense was one of the lines that Martha says, referencing Abu Ghraib: “I have the solution, George, I can transform the horror of the hooded prison garb into the perfect black dress.” You’ve been quoted in the past as saying that you’ve felt that your voice was being staunched because creative problem-solvers present a threat to consumerist problem-solving. In light of that, it’s a pretty amazing accomplishment, that although we’re brought to see Martha as this representative of that consumerist problem-solving, we also feel genuine compassion for her. Can you speak to that?

KF: That’s true. Martha is the protagonist and is the first voice, and I select her as the neurotic, but also I’m looking at Martha Stewart, or the relationship of Martha and George, and going beyond Democrat or the Republican. There are various levels to Martha. She comes from Polish immigrants and [George] makes fun of her for that… . I have a relationship to that, just from growing up in Chicago, which has a very strong Polish and Ukrainian background. I remember when Hillary Clinton was at that restaurant called the Busy Bee, which is no longer there, at North and Milwaukee, which was where she said her famous line, “I don’t stay home and make cookies.”

This is why Martha is catapulted into our imagination as a female with power. We allow her to be on a pedestal, because she only makes decisions in the safety of the home, where females can make the decisions. And, she is hyper-domestic, hyper-vigilant, as a mother and in her domestic duties. I think that in the sense of crisis and comfort, because we’re at war, we find comfort in her control over grapefruits or linens or whatever. Her dynamic is that she’s the “mean mom”—when they’re having their sexual romp, she’s the mean mom. She wants to be a better mother than her own mother, and that’s her crime. She wants to outdo her own mother, which I think is very Oedipal. I think everyone understands that. Then what happens, when the woman becomes the mother? As I said, everyone hates their mother, so you can’t win. George wins by losing, Martha loses by winning.

EF: That’s a great line. You’ve done a lot of work about oppression, abuse, and victimization and what it is to be female in a culture that really makes that very difficult. What was it like to give birth to a daughter…and to know that you were going to be raising her here?

KF: I was happy just…to be having a child; at that moment I wasn’t considering the gender. I think for me, seeing her experiences and seeing the fact that there are more opportunities for girls than when I was growing up, makes me very happy. Even in simple situations—when I first started going to school, you had to wear a dress. You know, [we had] home ec. When I went to college there were very few female professors. When I went to the Art Institute of Chicago and I looked through the collection, I thought Joan Miro was a woman. So, there really were very few mentors for me. The only one was Georgia O’Keeffe. I remember going past [her painting of] the clouds every day, every Saturday when I would go to the Young Artists’ Studio. I remember seeing the Jean DuBuffet, who I decided was a woman as well.

EF: At that time were there strong women in performance whom you admired?

KF: Yes, there certainly were at Chicago’s Art Institute. There were women performing, I think, at that time. Laurie Anderson for one.

EF: Were there other artists whom you remember being impressed by?

KF: I remember that Yves Klein came to the Museum of Contemporary Art. I think Joseph Beuys came to Chicago and I was aware of it. I was very young, but I was aware of thinking about creating without necessarily [making] an object. That was important to me, because of coming from more of a working-class background, and wanting to infiltrate capitalism and the relationship to the art world, which I still have, I still struggle with.

EF: What was your first taste of performance? When did you just get bitten and say, “This is it. I’m doing this”?

KF: I think I was always just interested in doing it but I was trained in the visual arts, so I didn’t look at it as being different. I mean I was doing conceptual work starting in seventh and eighth grade…. I was at the Young Artists’ Studio at the Art Institute of Chicago and I was reading all the time because I was a nerd. I would go to the library and just read everything I could on art, art history, and poetry. I was also watching what was going on in terms of political theater or political activism…it would be Abby Hoffman levitating the Pentagon. That looks like a performance, you know really, when thinking about it. So those things were happening in the outside world, where there would be a meeting of rock ’n roll or politics and guerilla actions which would be performances.

The first performance I did was actually in the cafeteria of the Art Institute of Chicago.

EF: Oh, that’s really amazing.

KF: I was performing, I think with some students…. I also did a performance in a class as a freshman or something like that. I was doing things very early and it wasn’t considered weird or strange. Unfortunately, I think our culture or educational system hasn’t progressed much. I had the privilege of being considered an artist and having that considered normal… really, it was a different time. At twelve, I was going downtown by myself. I was going to the museum, seeing the exhibitions, and it had a big impact on me. I was a participant in culture as an audience member from very early on.

EF: Do you remember when you realized that art could have the power to change things?

KF: I never looked at art as being able to change things. I look at art, or being an artist, as being a historical recorder.

EF: Why did you dedicate your book to Finley Peter Dunne?

KF: That is a relative of mine. His parents were Irish immigrants and at the turn of the century he was one of the most popular journalists…maybe like the Mike Royko of his day. He was a syndicated journalist, but he was the first…political humorist/satirist to write about politics but with an Irish brogue. It would be an Irish immigrant, Tom Dooley, who came to a bar… and would be speaking about politics, that was [Dunne’s] column. He also wrote many books. I thought it was interesting, that I do something similar, and I have a history of doing political satire.

EF: So it’s hardwired in your genes?

KF: Yeah, that could be. He was the first person to actually write in the language using the [Irish] dialect. That hadn’t really been done in that way.

EF: I’ve read that you are of Native American, Gypsy and, of course, of Irish heritage. How much do these people who have experienced tremendous voicelessness and oppression “speak” to you and tell you, “This is what we want you to talk about?”

KF: On my father’s side the idea of people who can’t speak is about mental illness and depression, which is something that I speak to in my family. My father committed suicide. Mental illness is something that we don’t understand. Also, I think that within the Irish part of my family, language is really important. Knowing that the language had been taken away and the sense that you had to use humor and to act like the child, the self-abusing humor. That oppressed people, whether it’s Jewish or Irish or African-American, using humor. You have to be laughed at…I learned that from my father’s side of the family. Also, I have different religions in my family. People in my family all married different people with different nationalities.

My mother was taken as brown, her whole life. I do remember going to Wisconsin and at the restaurant my mother would have to enter and sit at the back. I remember once going to Lincoln Park Zoo and my mother was sitting on the steps, nursing, and there were people calling her an animal. She would be looked at sometimes as being our domestic, rather than as my mother.

EF: She was substantially darker than you?

KF: Yes. When I look back now on living in a mixed neighborhood, that’s the term that they would use. I didn’t understand, it was sort of unspoken in a way. (People) were always wondering about her. That was painful and her last words to me when she died were, “When I see God I’m going to ask him what this race thing is all about.” I feel that is one of the most important issues going. I mean…I don’t have that appearance, but I saw it with the eyes of my mother, that she was always looked at every day when she went out. She had the gaze put upon her.

EF: Very early on, you describe a childhood of looking at these power dynamics and they’re intimately associated with your family. So you experienced this empathy with your mother, but also this sense of being different and being privileged, maybe, even in her company?

KF: That’s a good point, probably. I had a different access than my mother.

EF: And that foments a sort of a guilt that you have to deal with in your life?

KF: When I was a child, I think that at certain times I didn’t necessarily speak about it, my appearance. I didn’t think that I would be able to speak about it, because I didn’t experience it within my soul. But I did experience it in terms of my relationship with my mother, and seeing another story, if you want…whether it’s the shame, the feeling, the class. Knowing my mother and what she felt…is [knowing] that whenever she would be going out, she would have to endure the gaze. It’s being looked at in a certain way.

EF: It’s a very strange thing, because there is such a thing as not being white enough. Perhaps this is in part the source of your amazing empathic capacity. It’s in your work. I think people who have never even considered another person’s state of existence have to address it in your work.

KF: I don’t think I’ve done enough about race, though. And I think that now, at least, within my teaching I can address it…I love teaching so much. I love education…. I teach theory, history, identity, art and public policy. I teach the relationship of art to culture and society. I love doing that.

EF: Do you feel that there are parallels between this time and another time in history?

KF: Yes, the 1970s, at the time of Watergate. The Vietnam War and Watergate. I think there are some similarities.

EF: Martha says at one point, something about George’s intense yearnings and passionate feelings for Iraq being perverse, that it’s sexual tension. There’s this sense during the ’70s that so much of what we’re doing with Vietnam is a way of sexualizing…and eroticizing it.

KF: Thailand came out of Vietnam. The whole sex industry of Thailand really was developed out of Vietnam.

EF: I didn’t know that but the book got me thinking about war and eroticism and the psychosexual component of conquest and conflict. Can you talk about that, about the way sex works in George and Martha?

KF: I am using the sexuality on various levels. The levels I’m speaking of aren’t necessarily in terms of the relationship. The value of sexuality now is about not having intimacy, and I think early in my career I was using the body, which would then be looked at as being sexual. Now, with so much of the interest in porn and in Paris Hilton, there’s an emptiness about it. There’s an addiction, a neurotic sense of not having enough. It isn’t romantic, or there isn’t an emotional component. It could just be like filling the dishwasher or something—it’s just everywhere. I wanted to use the current trend of looking, with porn or sex within it…. I think what’s strange is now with this guy from Homeland Security, where you know a 14-year-old girl is involved or whatever…it’s the thinking or humanizing of celebrities within their own ways. Some of it I just find very, very funny.

My favorite one is Martha on her knees, and George is just saying, “Fluck, fluck, fluck Clinton.” I just think it’s hysterical. He’s saying, “Jesus!” as he’s orgasming. it’s just funny…I think it’s funny.

EF: I found myself saying, “This is plausible.”

KF: Diapering Bush, or infantizing him…I think that’s what he is involved in. I was trying to figure out; I mean, you can read The Bush Dyslexicon. I think another interpretation of his inability to form words is at the level of infants who are starting with language. It’s that level of development, in that he stays close to mom, or stays close to the womb, to the baby level. She facilitates his need or comfort level. On another level, in terms of a feminist discourse, which is what I think this book can give, or is meant to give, is anxiety—a castration anxiety. The fact that Martha is manipulating George’s maleness. That the symbol of the female, the mother holding his genitals, while he’s saying “Mommy’s a ball-buster.” That the mother is able to take away her son’s potency, that is the fear. I think that’s a very powerful image…I think that that should be in the Whitney Biennial. She’s just holding the penis and it says “Mommy’s a ball-buster.” I know it’s crude but I think it’s just speaking about a castration anxiety. [What with] dealing with the potency of war and what he’s also involved in, but then also how we as a nation, how are we living through, in the national narrative, these particular individuals.

EF: You went through this amazing time in your life, when you were at the vanguard of all of these censorship issues. When you go through something like that, is there a part of you that you have to force to drag along and do the hard things, a part that would have preferred everyone to like and understand what you did?

KF: I think that it isn’t about what I’m doing, that people don’t understand. People don’t understand themselves, and so they project their fears and their anxieties onto me.

EF: That’s an amazingly powerful statement.

KF: That happens to the artist. I think the question is “why do the projections happen to me?” I think it’s because the empathy that I have with others. My center isn’t necessarily in myself. I have the ability to put my center basically out of my body. Therefore, the projections can come onto me. At the time I was young, in my youth and in idealism, but I was an entity to put the projections on. I attracted that energy. I still do. I mean, it still happens. That’s really what I think I’m about, not necessarily what I’m doing but what other people are doing or not doing, or their fear of their own souls.

EF: So essentially…you exist in a liminal space. You’re not what you are, but you are what you’re perceived as being, and that makes you the thing that you’re perceived to be. How do you deal with the stress of that? How do you handle that, because you are Karen Finley, and you have a real life?

KF: I think Karen Finley, or what people consider Karen Finley, is what Karen Finley is. I think that…it becomes an imagined place. Maybe that imagination is what creativity is about; maybe there is some meeting place. I haven’t become advanced enough about that. I think I need to study quantum physics more. I think the imagined person, the imagined self, might have something to do with physics or with a different reality. How do I deal with it? The opportunity that I had with studying was wondering why this was happening so much to me. I think it was with my education and my patience and my education as an artist to take things, take a picture and turn it upside-down. Because of creative problem-solving, I was able to come to some of these conclusions, just the composition that I was given, to try to make it work by turning it around, inside out. It was in my training as an artist and in problem solving, that I was able to deal, and grow from the situation.

EF: Some of the best artists that I know have incorporated and interpreted social dysfunction into their work. Can you talk about that?

KF: Some of these problems I’m thinking about, like Jesse Helms and his projections and his sexuality and his desire for me, or maybe even the female body, when I’m covering my body with chocolate. I think the horror or the rage and the desire might really be about…transferred rage onto the black female body, on my body. I have a lecture I do on that.

EF: You need to do it here, this is very current. This is exactly what we need to be talking about.

KF: I was a safe place to transfer that emotion onto. People look at Strom Thurmond, the original piece was about wanting the young woman, young African-American woman, that was the symbol…by covering my body, I’m transforming my body. That’s what I’ve been considering. When I’ve talked to women about that, women of color, I get a positive response.

EF: So all that empathy that you had with your mother really allowed you to plug into and understand that?

KF: Unfortunately, I don’t think that has come out enough. It comes out unconsciously, but it doesn’t come out where people are speaking about it.

EF: Considering the political climate, do you ever regret not accepting the offers Finland and other countries made to you during the NEA Four days, to move there?

KF: I think that would have been the easy way out. There were artists I know that went into exile, whether it was Beckett, or Josephine Baker. I felt I had to work the process, and I felt that my work that I particularly did, was always about a comment on American culture. I just never considered it.

EF: But working the process, for you, must have required some sort of spiritual discipline or commitment, because it was such an arduous thing to have gone through.

KF: Yes, it was. It took probably about ten years. I had a solo exhibition at the Whitney and I lost that exhibition five days after losing the case. It was suggested to me that I…restart the process, because we would be having proof of the damage, and I thought that I didn’t have the strength, but also I felt that I would be looked at as just being a litigator. I didn’t think that that would help the cause. I think that they would have to have sort of a fresh face or a fresh start. I think that…in the history of the courts, whether it’s going to be eminent domain or stronger issues, which are even more important issues, I look at what I was involved in as a step on the staircase.

Karen Finley was born in 1956 and grew up in the Chicago area. In 1982, she received her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and moved to New York City, where she became part of the city’s performance scene.

Inspired by news reports of Tawana Brawley, a 15-year-old girl who was reportedly raped and found smeared with excrement in a garbage bag, Finley performed her controversial “We Keep Our Victims Ready” in 1989. As part of her performance, Finley covered her naked body in chocolate, then festooned herself with tinsel, stating that “no matter how bad a woman is treated, she still knows how to get dressed for dinner.”

As a result of the performance, Finley drew the attention of Senator Jesse Helms, who claimed that the work was offensive. Finley became known as one of the NEA Four, four performance artists whose NEA grants were declined in 1990 after vocal criticism by the senator. Although the artists won their court case for reinstatement, they ended up ultimately losing their appeal to the Supreme Court. Hence the U.S. government is allowed to withhold funding predicated on whether it is deemed that “standards of decency” have been violated.

Finley, a recipient of an Obie Award as well as a Guggenheim Fellowship, has performed and exhibited around the world. Among her published works are: Shock Treatment (1990), Weekly Meditations for Living Dysfunctionally (1993), Pooh Unplugged (1999), A Different Kind of Intimacy (2000), and George and Martha (2006).

She is presently a professor at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, where she teaches Art and Public Policy.