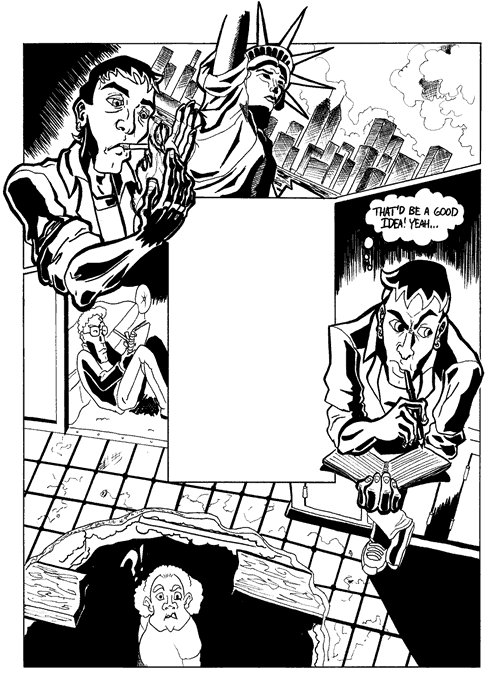

Phenomenon Comics Editor in Cheif, Jonathan Helland

By Emily Anderson

When my friend Jonathan Helland was seventeen, he used to pour Zippo fluid into his cupped palm, spark it, and use his flaming hand to light his cigarettes. So I wasn’t surprised when he dropped out of college, moved from Minneapolis to New York, and started a comic book publishing company with his best friend Ben Wood. Three years and $30,000 later, Phenomenon Comics is self-distributing the first 5,000 copies of their new title, Blackpool. Somewhere in between, Jonathan wound up in Decorah, Iowa, a town where there’s no comic book store at all. A lot of stories start this way: a kid with a dream moves to the big city, works hard, and succeeds, big time. Or fails, more quietly. It’s hard not to think in terms of success versus failure. Sometimes, the more interesting story falls somewhere in between–maybe even somewhere in Iowa.

I interviewed Jonathan about his business, and his love–writing. He paraphrased his idol, Ray Bradbury, to describe his creative process. Writing is his business, but it’s also about “falling in love and staying in love.” Somehow this process, at its best, manages to evade simple ideas of success and failure. When he left Minnesota in August of 2002, Jonathan was spending $50 a week reading comics like Hellblazer, Preacher and The Invisibles as well as old issues of Sandman. He was also writing a serialized Victorian thriller for his college newspaper. “I really, really liked doing serialized fiction,” he says, “and when I dropped out of college, I didn’t know what the hell I was gonna do. So I called Ben and he said, ‘Why don’t you move out to New York with me? We can start a comic book publishing company.”

So Jonathan moved into Ben’s apartment in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan. They ignored a gaping hole in the kitchen floor and set to work. Or tried to. Both Jonathan and Ben are writers, so their main problems initially were finding artists to draw their comics and interesting investors in a nonexistent product in order to pay the artists. In this scenario, chickens quickly became eggs. Jonathan and Ben scoured the city simultaneously seeking artists and investors, and quickly discovered the difficulty in finding one without the other. They hired a message service to answer their calls while they worked their day jobs, and took the subway around New York, taping flyers at every art school and comic book store in the city. They received about 60 submissions of artwork, though only “one of them was any good….it’s more than being able to draw, [comic artists] need to have narrative story-telling skills… need to know a lot about sequential art, which a lot of people don’t.”

When they found their artist, they couldn’t pay him at a discounted rate of $50 a page, let alone the going rate of $100 a page. While writing a business plan can be a pain in the ass–a “colossal waste of time” even, it’s easier to write one than to find someone willing to stake $200,000 to start up a comic book company. Jonathan and Ben dreamed of having someone to help finance and manage the business aspects of their company, so they could focus on their creative work.

They decided to offer a share in their company (originally called Inwood Comics after their Manhattan neighborhood) to a business manager, who could handle the financial aspects of the company and find them investors. Thanks to the economic downturn, Jonathan and Ben were able to interview a series of MBAs and “professional types” for this position. They held the interviews at a sandwich shop, because they couldn’t afford an office and didn’t want to take interviewees to their squalid apartment, where both the sink and ceiling were beginning to drip.

At first, they thought they were in luck. They hired a man who had been laid off from Marvel Comics and claimed to know people in a position to invest in a new comic book company. “But he didn’t do anything, and so we fired him,” Jonathan said. How strange to be twenty-three, broke, scruffy, and fire an MBA. “We were pretty passive aggressive about it…we just stopped scheduling meetings with him and stopped telling him jobs to do…eventually he called us and said he’d gotten [another] job.” So Jonathan and Ben had to tackle the business tasks by themselves. Jonathan learned Excel to produce spreadsheets and convinced his dad to invest $25,000 in the company. Not as much as the business plan called for, but it was a start. They divided their job responsibilities: Jonathan became President, and Ben Editor-in-Chief, and started work on their first title, State Secrets, a 1930s spy comic pitting a secret international organization against Nazi occultists. Handling the writing, editing, and managerial concerns for their company took a lot of time, which took its toll on two overworked friends sharing a tiny apartment. Beers and burgers became business meetings. Living with a best friend became “living with [a] boss.” It didn’t take too many internal disputes for Jonathan and Ben to switch jobs one day while waiting for the subway: “[Ben] just had to call me out because I was an awful president…I’m not an initiator; I’m not a self-starter, I’m not a planner, I’m not organized–he’s all of those things. So, yeah… now I’m the Editor-in-Chief. It’s weird to not want to get a phone call from your best friend because it means you probably have a bunch of work to do.”

Writing became not just something Jonathan did when he “felt like it, or had a really good idea,” but something he did to pay back his investor. “You can’t say, ‘OK, I’m going to put this one off for later until I feel like working on it again.’ Or, ‘I guess this one isn’t so good after all when you’ve invested not only a bunch of your money and a shitload of your father’s money and a year and half of your time into it, it’s something you need to finish…so that makes it feel more like a job. And nobody likes a job. They say ‘do what you love,’ but if you do what you love as a job, it’s not as fun as if you do what you love because it’s how you like spending time. There was a large chunk of time when we just forgot why we were doing what we were doing…we weren’t thinking about, ‘Wow, we’ve created art and we’re putting it out into the world,’ or on a more basic level, ‘I have this story to tell and so I’m working on telling it.'”

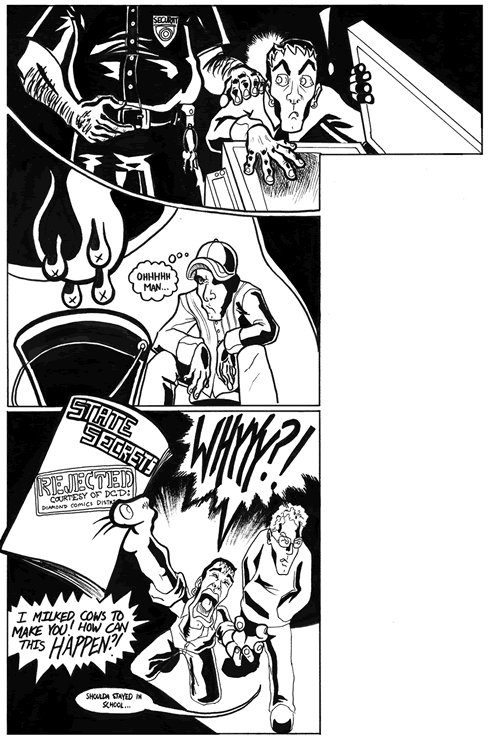

In the fall of 2003, Jonathan and Ben were concentrating more on just getting by than on “making art.” Problems with their negligent landlord were escalating, as the holes in the floor and ceiling were growing. Out of spite at their neighborhood, they changed their name from Inwood Comics to Phenomenon Comics and juggled day jobs, writing and administrative work, and appointments with tenants’ rights lawyers. Additionally, they were preparing to meet an important deadline they’d set for themselves: they were going to submit their work to Diamond Comic Distributors, Inc. New comic companies submit mock-ups of their work for review to Diamond Comic Distributors, Inc. (DCD), which “pretty much has a monopoly” on the comics industry. Once DCD approves a comic book, they offer it to retailers all over the country via quarterly catalogs. DCD then orders from comic book companies based on retailer interest. Comic book companies do not receive commissions from sales, but, since they’re paid in advance from DCD, they don’t have to eat the printing costs of copies that don’t sell. The downside is that DCD makes it hard for companies to distribute their own work, and their standards determine what comic books appear on store shelves: “Almost everybody goes through DCD. We didn’t even think about going through anyone else.”

Before Jonathan and Ben could finish work on State Secrets, their legal issues with their landlord were finally resolved: “We were evicted–or rather, when we won our settlement against [the landlord] we had to move as part of the agreement.” Simultaneously, Jonathan was fired from his office job, for sneaking into the office to use their printers for Phenomenon Comics business. Oops. No money and no place to go in New York City is no fun. It was a dark time. Jonathan and Ben decided to cultivate some Plan Bs. Jonathan decided to leave New York and go back to finish school. Ben decided to stay in New York. Jonathan’s move to Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, can be interpreted not as a defeat–the failed bumpkin leaves the Big Apple and goes back to the farm–but as a strategic retreat: after investing nearly $25,000 to pay artist and administrative costs for the first three issues of State Secrets, there was no going back. There was no farm. There was nothing to do but soldier on, telecommuting from Iowa, hoping against hope that DCD would approve State Secrets and that it would sell–maybe even enough to pay back the investors and get them out of this rough, disheartening business once and for all.

It was a relief when they finished the full mock-up of the first issue of State Secrets and submitted it to DCD. A relief that they’d met their deadline and that it was now out of their hands. If their comic were accepted, State Secrets would be distributed nationally within three months. All Jonathan and Ben had to do was wait. Waiting is rarely portrayed as a heroic quality. It’s not part of the kid-with-a-dream story, it’s not included in the movie-montage of success, but it’s a very brave thing to do: to put a year’s effort out there and hope that it meets someone else’s standards, hope that no one will be able to tell you that you’ve wasted your time.

Unfortunately, DCD did not approve State Secrets for national distribution. They felt the artwork was “amateurish.” Amateurish. Ouch. After all the work of finding the best artist they could, of getting Jonathan’s dad to invest money, paying the artists, the colorer, the letterer, rejection came as a terrible blow. And, if it weren’t for the fact of having some serious financial stakes on the table, it would’ve been easy for Phenomenon Comics to disband, to try something else. And, in their own ways, Jonathan and Ben already were trying other things: Ben got a role in a Coke commercial, Jonathan started a physical anthropology major in college. But they didn’t give up. They couldn’t. They found a new artist, Terrell Bobbett, and started working on a new title, Blackpool , a horror comic “in the tradition of H.P. Lovecraft, set in a fictional college town in Vermont and starring a punk-rock bartender and a freshman girl who has a questionable gift of experiencing people’s deaths in her dreams as they’re happening. They sort of always end up over their heads as the people in town conspire to harness the thing that lives in Blackpool lake.”

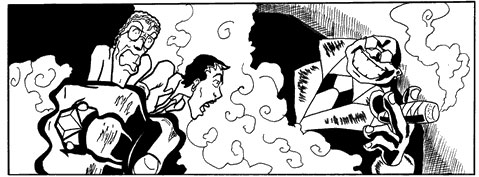

Even though Jonathan and Ben must have sometimes felt that they, like their Blackpool characters, had ended up over their heads–or were even being conspired against by landlords, bosses, and comic distributors. They kept their chins up and divided their energies and resources between working on Blackpool and promoting themselves, so that they could have a better shot at being chosen for DCD distribution. They printed business cards, flyers, and posters, and flew themselves and their artists to San Diego to attend ComiCon, the largest comics convention in the world. At ComiCon, they made sure to “dress the part” of a start-up comics company in a kind of good-cop, bad-cop routine. Ben tidied himself up and wore a suit to project a professional image; Jonathan didn’t shave and wore a Che Guevara T-shirt to project a punk-rock, DIY attitude. They attracted some notice, too–or, at least, their artist Terrell did. Terrell’s work was immediately recognized by representatives from Marvel Comics, who offered him a job on the spot.

This fall, Phenomenon Comics will print and independently distribute 5,000 comics of the first issue of Blackpool , several months in advance of DCD’s distribution deadline. Things seem to be looking up, despite Jonathan’s understandable anxieties: “I’m constantly terrified that we’re never going to accomplish anything and that I just dug a giant hole in my father’s bank account that I’ll be years paying off. And theoretically, if Blackpool gets rejected [from DCD], I’m in a lot of trouble, but there’s a very real possibility that I’ll have a comic book in stores by the end of the month. I’m excited now to see [my] script come back as a colored, lettered comic book, because at no point in the process up till then does it look like a comic book. Once you have those word bubbles in and it’s suddenly telling a story, it’s like, oh, so this is what I’ve been making for the past few months! Holy shit, I made a comic book!”

If you’re still thinking about starting a comic book company, Jonathan has some words of advice: find an artist who will work for free for the same reasons that you’re doing it. Or be an artist. That’d be a great plan. Be able to draw. And have one title until that title gets published. Don’t try and think too big. Don’t try and plan too far ahead. Make a comic book. Make a full comic book before you even think about starting a business. The business will come when you have a product to sell.

Illustrations by Feras Khagani

March 2005