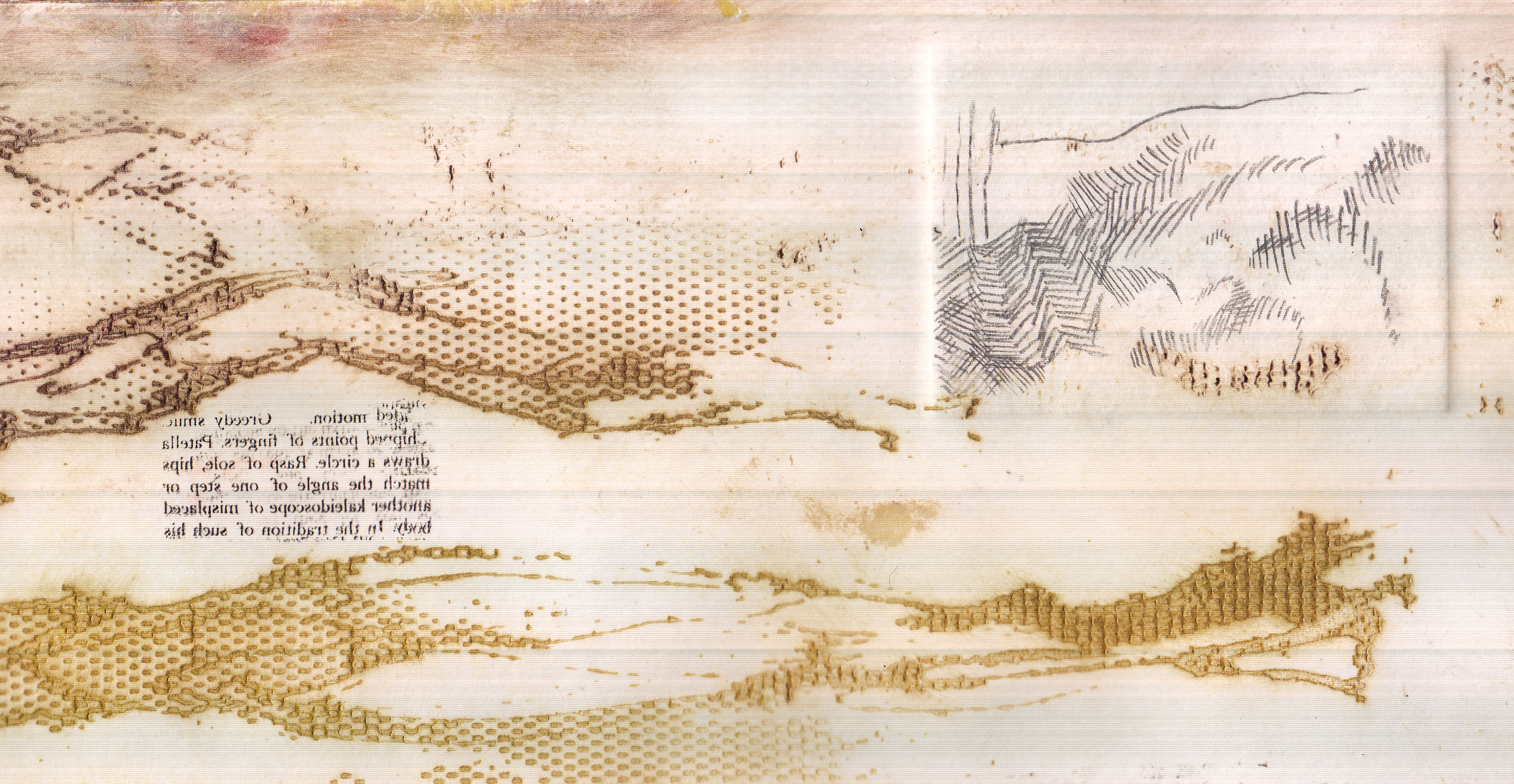

All photos courtesy of Yvette Monahan

Irish artist Yvette Monahan spent a year photographing the landscape and locals of Bugarach, a mountain in Southern France rumored to be part of the Mayan Apocalypse, in the year leading up to the anticipated date of December 21, 2012. The mountain and its mysteries have inspired artists and writers from Jules Verne to Steven Spielberg, and have long featured in Holy Grail, UFO, and other esoteric conspiracy theories.

Monahan’s photographs in the days leading up to the potential Armageddon capture this allure, presenting a place that appears timeless despite the project’s very specific time frame. A mystical quality permeates her portraits of locals who live in unconventional ways on the mountain, in which the subjects sometimes seem to embody mythical archetypes.

Her work references its own romantic heritage, nodding at the idea of the sublime. At the same time, it engages with the landscape on the hopeful level of a believer. The ambiguous presence of the mountain buzzes throughout the photos, informing them with both desire and trepidation. Our knowledge that nothing occurred on the 21st gives the photos a wistful undercurrent, the sense of the area as another unrealized Arcadia.

VC: Where did you first encounter the story of Bugarach, and what led you to photograph it in the year leading up to 12/21/12?

YM: I was doing a course in France in 2011, and staying with a friend. Her husband was driving us around when he began to tell me the story of this mountain, and that some people believed that the end of the world was about to occur. This was an idea that all of the people in my meditation group believed: That there was going to be this change of consciousness on that date. I found it a bit disconcerting. One day I was telling a friend about the story when we were having tea and I went, “Oh my god, I have to do something about this.” And it was just one of those light bulb moments. I felt that I had to go to this place, and be there, and be around that story.

VC: There’s a certain emotional charge behind the images. At the time, did you hope that this change of consciousness you mentioned would actually happen?

YM: I didn’t know, but I decided I’d be open either way. Lots of people there were kind of talking gobbledygook at some stages, and there were varied opinions circulating. I decided that I would be open to either outcome. By the end, I kind of wanted something to happen. You feel like Chicken Licken, “The sky is falling in,” that it would be good for a change to happen, but nothing did [laughs]. Visually, it would have been great if frogs had fallen from the sky, or if there was a massive thunderstorm that broke open the mountain or something. There was a lot of media there. The mayor got the local gendarme to come in and police it, and to go in and out you needed a special permit. There were German TV crews and Japanese ones, and I think they just went and got drunk in the end. It was kind of jovial. The locals didn’t want anything to do with the story, really.

VC: The photographs seem to maintain ambiguity about the outcome of the prophecies. Some images from the book, like a long row of caterpillars moving across the ground, could be found both beautiful and unsettling.

YM: I suppose that was the thing, you just weren’t too sure whether it was a positive or a negative in the broadest sense of those terms. Or, I suppose, Arcadia versus Apocalypse. In terms of photography, you try to go for something that’s visually arresting to actually photograph, and you’re swept up in that. Then, in the edit, you come back to those questions again.

There was part of me that was half terrified, because they were saying that they’d have the French Foreign Legion down to do the guard around Bugarach on the date, so that if anyone reacted they wouldn’t have a problem shooting French people, because [the Foreign Legion] are not French. These are just rumors, adding to the tension of the place. You’d definitely get stopped late at night if you were driving around, and asked what you were doing and why you were there.

VC: Were you stopped while you were shooting there?

YM: Yeah, they would ask what you were doing, and I’d have to say I was on holiday with my auntie or something. Because there are a lot of people living alternatively, they might hassle them a little bit. There’s a big hippie market on a Sunday where people would get together, and that’s where you’d hear the gossip.

VC: How did you engage with the off-the-grid nature of the locals’ lifestyles in the photographs?

YM: Some people are into living alternatively, or just with minimum interaction with money and electricity and things like that. So they live in yurts or teepees. One man I photographed lived in a cave, and he just seemed to live off things that he found. There are hot water sources in the area, so they bathe in those instead of having running water. And there are people who just live very normal lives. There was a great mix of people, and I suppose that was a problem with photographing it. I didn’t want it to be about living alternatively, that wasn’t what I was trying to get at. I was more interested in kind of feeling about change, and the possibility of change. The alternative community would have been easier to photograph.

VC: It’s more tangible.

YM: Yeah, and people were quite wary about being photographed for the project, as well.

VC: How did you make people feel comfortable being photographed? One portrait in particular that stood out to me was the man standing in the forest with a pair of horns, dressed as Pan.

YM: Yeah, Pan. Well, he busked as Pan at the market, and dressed up and sang and played the flute. He was speaking English, and I was so tired of speaking French that day that I just went up to him and said, ‘Hi, I need someone to talk to!’ We became friends, and I went up to visit him. He wanted to get some water from the river, so we went down and did that, and then he wanted to get some pictures for his mother of his new Pan outfit, because she used to help him out with his outfits. So we did some pictures. He had had a difficult time, he went to a very expensive boarding school in England, and he had had some problems there. He was living in the woods in this friend’s summer house, but it was a little hut just in the middle of the forest. He was staying there to try and work through his issues. I felt for him, you know, he’s a very sensitive guy.

With other people I’d be staying in the same place, on a farm where there were a few people, and just get chatting. I’d try and organize and meet people that I thought were interesting. So I was knocking around, making friends. I’d swim in the river everyday, so then you get really comfortable, being in the same water as people. They see you swimming and you see them, and we might have casual exchanges. Gradually, they’d see you with the camera, and then the next time you picked it up they’d not really react to it and just be really relaxed. Afterwards I would take their details and send them prints. I photographed a lot of people that aren’t in the final project.

VC: How did you decide on the 22 photos of the final project?

YM: Twenty-two is a sacred number in the area, so I decided to go with that number of pictures. I wanted to work a lot of those things about the area into the way the book was made so that it was integral rather than explicit. The number is just there, nobody really notices it. It becomes part of the narrative, but in a really non-explicit way.

VC: Some of the photos reference Caspar David Friedrich and the Rückenfigur, the image of a human figure gazing upon the sublime landscape. How do you relate to a romantic tradition in the work?

YM: I suppose the reason I came to love Caspar David Friedrich was really through Clare Richardson’s photography. There’s a darkness to her work, so it’s not just romanticism in a traditional sense. I suppose my aim was to try and balance that out with some things that were more ambiguous, so that the whole thing didn’t lead to some kind of romantic view. It was definitely a challenge, because I do think it’s nice to be drawn in by color or lovely sort of beautiful things. You react to beauty. Rückenfigur was in and out of my head the whole time and eventually I left it in, because I felt like it was just a viewpoint. It’s definitely something to question all the time.

VC: Were you inspired by other artists and writers who’ve made work surrounding the mountain?

YM: Yeah. Steven Spielberg [laughs]. At the time, I felt everyone I was drawn to had spent time at that area. I thought everything in the world pointed back at the area. I just had such an obsession with that place that everything seemed to have a connection to either the Cathars or the sacred bloodline story. I mean, with most of this stuff you can take it or leave it, but that’s why I’m interested in myths and stories. They come out in this way that’s not history, but then, what is history? All of this stuff. Because I had no other way to kind of connect things, I’d try to just follow any little link I saw and go with chance and coincidences as part of it.

VC: Does knowing what happened on the 21st change how you view the work, as opposed to when you were taking the photos?

YM: I stopped on the 21st of December, so that I wouldn’t be influenced by the outcome. It was really about the build up. Nothing had been realized, in one sense. But I think, in retrospect, what I found was that maybe I had totally changed from doing the project. In a sense it was more a personal experience than anything. It gave me an excuse to look at things that were of interest to me, and to go right into them. And I had some very bizarre experiences there. Good ones, but strange. I think I was really changed after them.

I went back to the area in the summer, to give some of the people the book. I found I just didn’t feel the same tension in the place. Maybe that was just me. Even though people were talking the talk, I just didn’t take it on board anymore, because there wasn’t the same overhanging prophecy. I felt like I couldn’t take any pictures there anymore. It just didn’t mean as much, and it didn’t have the same tension in it.