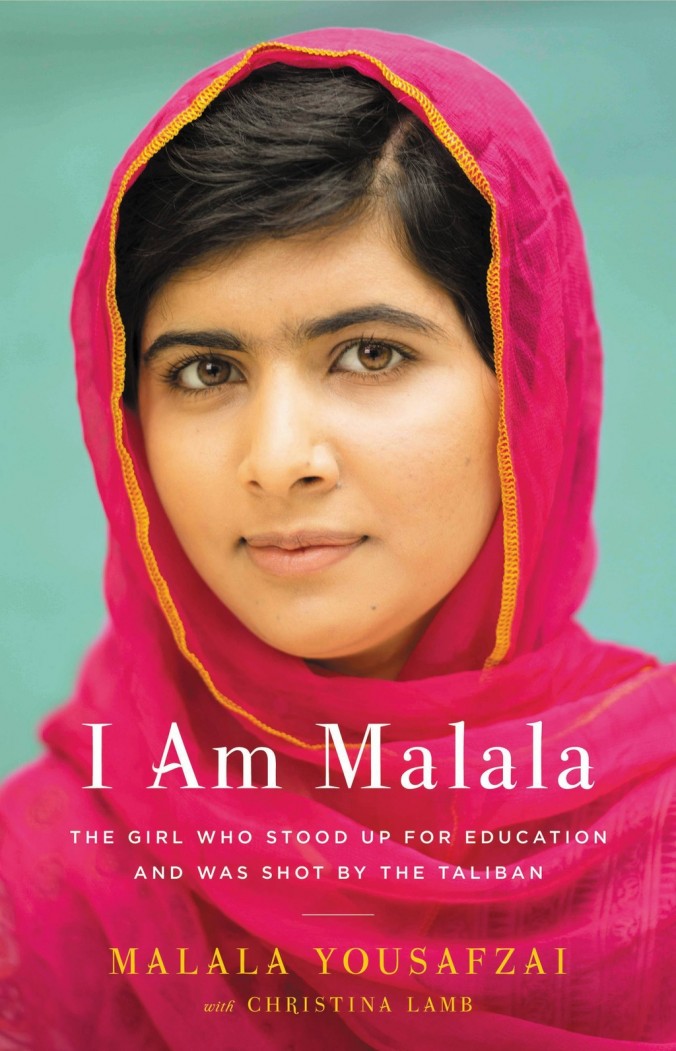

A review of Malala Yousafazai’s I am Malala

I Am Malala (2013) by Malala Yousafzai and Christina Lamb reads a little bit like the Diary of Anne Frank. It tells the story of an ordinary girl reporting on extraordinary cruelty. But while Anne Frank found refuge in secrecy, Malala Yousafzai has fortified herself with publicity — a political move that saved her life last year when she was publicly shot in the head for refusing to surrender her right to go to school to the Taliban. Sixteen-year-old Malala Yousafzai may be an outcast in Pakistan, but she’s an icon for the rest of the world.

Her memoir, written by Christina Lamb, a British journalist and foreign correspondent of the Sunday times, describes how a fiery chemistry of political talent, familial love, and difficult times has pushed Yousafzai to the forefront of the fight for girl’s education in Pakistan and elsewhere. In the book, Yousafzai chronicles the surreal transformation that turned her beautiful home in the valley of Swat into a post-Taliban wasteland.

For an American audience, I Am Malala functions as an insider’s report, filling out our fragmented and tragedy-saturated perception of Pakistan with a more realistic image of the country. If you have read about Pakistan in the newspaper, you should read about Pakistan in Yousafzai’s memoir. Yousafzai grew up in an ecological paradise; a destination for vacationers, where her father ran a school for boys and girls, and her mother ran a stable household. When the Taliban came to power both she and her father, distinguished themselves as political activists. Yousafzai recorded the deteriorating status of her Valley through an online blog and underwent interviews with foreign journalists who often sought her out as she gained notoriety. Fazlullah, a charismatic orator and Taliban leader based in the mountainous region of Northwest Pakistan, permeated Swat valley with Islamic fundamentalism through an illegally maintained radio station. Bent on imposing Sharia law in Swat, the constricting forces of Fazlullah and his followers distorted Islam in the region. The valley became a site of everyday violence against men and women, and women saw their civil rights withdrawn and demonized. Religious monuments that did not fit within Sharia Islam, such as ancient Buddhist statues, were destroyed, and any kind of political opposition (even one from a teenage girl) became a target. When girl’s education was banned in Swat, Yousafzai was not cooperative and she was shot at close range with a colt .45 in return for her opposition.

The international response to the shooting of Yousafzai brings to light a telling example of the progress we have made in developing cooperative relations as a global community. While transcontinental trading routes flourished as early as the fourteenth century, globalization is understood to have come about at the beginning of the 20th century. Mediating between the local and the global hasn’t exactly been smooth, as globalization and global capitalism have enabled countless injustices and violations of human rights. While the communication technologies that bring us together have not always been used for beneficial purposes, examples like the case of Malala Yousofzai have illustrated that international communities can work together to stand up for women’s rights. When world powers come together over a specific violation of human rights, such as the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela, it can sometimes override the verdict of a foreign government by simply voicing disapproval en masse. International support from Germany, America, Singapore, The United Arab Emirates, and Britain flooded to the unconscious Malala Yousafzai after news of the attempted assassination reached the rest of the world. She was even removed from the Combined Military Hospital in Peshawar Pakistan and relocated to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham England, so she could receive better medical help. Neither the equipment, nor the care at the military hospital in Peshawar would have been sufficient to ensure the survival of Yousafzai. Instead it was the accessibility of resources abroad, facilitated by technologies in communication and transport that saved Yousafzai. Distinguishing herself as an adversary of the Taliban was dangerous, but in that act of self exposure, Malala Yousafzai developed a social safety net that connected people around the world to people in the Valley of Swat. She tapped into the interconnectivity of countries and made herself a part of a larger community that had the power to take care of her when her own Valley was struggling to take care of itself.

Yousafzai’s story has inspired hope and controversy in Pakistan, but the country is too pinned down by the menace of the Taliban to put forth public discourse regarding the degeneration of girl’s education and women’s rights. While Yousafzai has become a rallying point for activists all over the world, her own country is still fighting for the general restoration of peace. But although atrocities like the Taliban domination of Swat continue to wreak havoc on the lives of civilians, local crises can become more logistically and psychologically manageable within the global context. We have more space and resources to work with, so we can use it to create refuge for people when their home country is unsafe. We can use international consensus to intervene on behalf of victims. Through modern technologies, we have access to a broader perspective that we can use to provoke progress in ourselves and in other countries.