Hamid Ismailov Talks to F Newsmagazine about the brief life of an “Olympian”

“This novel shows the xenophobia in the very beginning of the breakup the Soviet Union. Now these tendencies have become sort of insane in Russia,” says poet novelist and journalist Hamid Ismailov. “Russia, possibly, now is the most xenophobic country in Europe, if not in the world.”

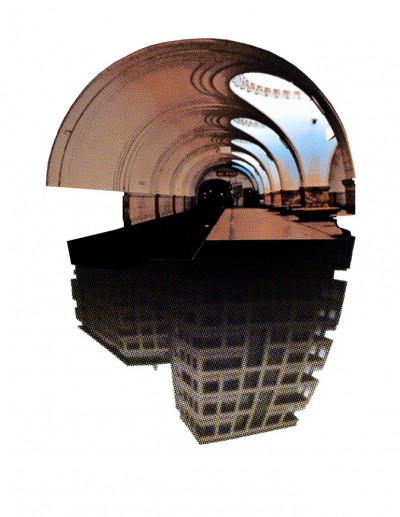

The Underground, Ismailov’s latest novel published in English, depicts the brutal separation between the hopes and realities of social integration on the threshold of the collapse of the Soviet Union. The dark and picaresque tale follows the life and death of the young Mbobo (also the book’s title in Russian) in a series of vignettes marked by the grand stations of the city’s metropolitan transportation system.

Moscow’s underground was how Ismailov began to understand the layout of the city as an immigrant. He recollects, “We lived on the surface, but all our communications, all our correspondences with different parts of Moscow were through the underground, it was our habitat. We moved around, knowing just metro stations.” In The Underground, the stations became a metaphor for the dreams and derelictions of the society above ground. The connotations of the Soviet term suggest underground life, underground thinking, and the cultural underground. At times, this is laid out explicitly in the fantastical reminiscing voice of Mbobo, who throughout the novel narrates from an unnamed earthen tomb:

“The construction of such magnificent stations as Sokol amid the maggoty darkness was a subconscious hint at fashioning the heavenly homeliness of life, albeit underground, in the very place where hell is generally supposed to be […] I would dare to venture that the best museum of Communism and the Soviets is the Moscow metro…”

Mbobo is the sobriquet given to the formally-named Kirill by his mother. Named Moscow, she is a half-Russian, half-Khakassian limitchitsa (immigrant with permission to work in Moscow) from Siberia. Mbobo’s father is an absent athlete from Guinea who competed during Moscow’s 1980 Olympic Games. Ismailov explained that a generation of Afro-Russians born in this era was cynically referred to as “The Olympians.”

Despite not knowing any “Olympians” before writing the novel, Ismailov wrote about this generation because of his personal experience of living in Moscow during those years. “I took to the extreme: the experience of my daughter, because she was, in a way, mixed race. She was different from other people, quite different. I knew her friends and I used quite a lot of this experience and my extensive experience living in Moscow … We were unsettled. It was difficult to find a place to rent at that time, being a national minority. Though we were perfectly, whatever, ‘normal’ Soviet people, there was a kind of distrust. I don’t know. Narrow thinking.”

Born in Kyrgyzstan, the author moved to Uzbekistan as a young man and now lives in London, England, where he heads the Central Asian division of the BBC’s World Service. Between 1984 and 1992 he lived in Moscow with his family. After the USSR broke up, they moved back to Uzbekistan with hopes of living in a fresh and revitalized culture. A few years later, dictatorial tyranny and censorship drove them back to their Moscow apartment (that became the setting for this fictional novel) before they ultimately headed into Western Europe.

Ismailov conjectures that during his time in Moscow, “the underground was the cheapest, the closest to communism, in a way, because you wouldn’t care about money. You couldn’t buy anything there. All you were left with was people and people’s relationships, apart from the sort of pragmatic action of traveling from one place to another place. The communism was, in a way, achieved underground rather than on the surface … a utopian idea that has no place on earth buried underground from the beginning. So it was a paradoxical idea, the paradise on the earth, but under the earth, under the soil.”

In The Underground, the character Gleb, one of Kirill’s stepfathers, is an erudite though violent and alcoholic man who writes for the international journal of the USSR Friendship of the Nations. “Yes, Uncle Gleb was a hollow man,” muses Kirill, “and if I had to compare him with anything at all on this earth, I would compare him with the whistling cavities of the dark metro, their grayness occasionally lit up with bursts of uncommon beauty.” Gleb calls Kirill “Pushkin,” a reference to the fact that this progenitor of Russian literature had an Ethiopian grandfather. The real poet Pushkin had an unfinished book portraying the life of his grandfather, who was employed and educated by the Tsar in the 18th century.

Race relations in the USSR certainly differed in ideological objective and actual fact. In pursuit of class-consciousness and capitalist decolonization, the Soviet Comintern earnestly began its recruitment of African Americans in 1928, training lawyers to unionize US workers. The 1935 Russian film Circus portrayed a white American circus performer and her mixed race son (played by the child of a recently emigrated American actor, Lloyd Patterson, and his Russian wife), fleeing persecution and living a life of social acceptance in the USSR. In the 1950s, an Everyman Opera production of Porgy and Bess visited Russia, reported on by Truman Capote, as part of a campaign to promote cultural exchange (from the US side) while purportedly highlighting the extreme injustices in American society (from the USSR angle).

The racism portrayed in The Underground, set during the disintegration of the USSR in the 1980s, highlights the increasing hypocrisy of a society predicated on actualizing egalitarian values, as those values were being undermined.

“Communism is about equality, but with this equality, you can become a sort of paranoiac about becoming more equal than others,” says Ismailov. “Parents were uncompromising in that. They were beating their children. They were ruthless towards children because they wanted them to become a sort of superhuman, every child. That was my idea: that you can live the sort of lives of the heroes of Dostoevsky, not knowing you are going through it.” The adults throughout the novel, dissolute failures at embodying utopian perfection, abandon personal hope to hedonism, fucking, drinking, and ultimately embezzling (after voucher-isation) without inhibition. The young generation at the curbside of the USSR is left to fend for itself, carrying the weight of their forebears’ misadventures.

“Realistically, everyone understood that he was not up to these expectations, which were put upon by the society, by the parents, by the organizations like Oktober, or Komsomol, because these expectations were ideological, they were utopian. What happens in the hearts of these children, who are asked to be super-humans, but who are just normal children?” Despite Mbobo’s achievements as a straight ‘A’ student with a keen memory for poetry, he is deeply self-deprecating throughout the tale, which is supported by the reckless care he receives from his parents and the cruelty of strangers. His feeling of not being able to measure-up, is symbolic not only of a repressed minority, but rather the condition of a society as a whole with unachievable goals.

The Underground, in this way, is not about one particular kind of person, but rather the pressures and contradictions facing many Soviet people growing up during this time period. “I personally feel ‘Russian’ in many cases as well,” Ismailov says. “I was brought up amongst Russian literature and Russian culture. The sort of the cultural code, the cultural DNA is sitting inside of me. I know the jokes, I know the references, I know everything about them. I also have the DNA, for Uzbek literature and Uzbek culture and so on and so forth. Its kind of a schizophrenic feeling of ‘Russianness’ which sits in every Soviet person.”

The locations, writers and poets, and social events that take place are meticulously realistic. Ismailov imparts that he “tried to save, to maintain the Moscow of that time in its full stereoscopic glory. I wrote it for Russian readers. It was a monument to that epoch.” The characters in The Underground are passionate residents of Moscow, with ancestry in Central Asia, Siberia, and Africa, as well as autochthonous natives to this central city of the USSR. Illuminated by Ismailov’s poetic prose, their hopes and despairs are beautifully evoked through the inner monologue of Mbobo. As the reader bears witness to his life, love, and perishing, the language shifts from that of a four-year-old to that of a young man in his twenties. The misunderstandings of childhood develop into worldviews and deserted conclusions.

The Underground was originally published in Russian in 2005 and is now included in the school curriculum in the province of Samara to teach children about tolerance. Recently translated, the novel came out in English as an e-book in December 2013. His third novel translated into English, it follows The Railway (2006) and A Poet and Bin Laden: A Reality Novel (2012). His fourth, The Dead Lake, about young boy in Kazakhstan who never grows up after falling into radioactive waters, comes out this February in paperback.

[…] F News magazine review Transitions Online review […]