After eight years of hesitation, the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) has finally installed the exhibition Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine in the American wing. The recent publication of show curator Judith Bartlet’s book Art and Appetite (on display in the gallery’s reading room) may have lead to this delay, but regardless, the show proves to be a in-depth consideration of the subject of food within U.S. artistic practice. Working from the content of Bartlet’s text, the exhibition has a thoroughly pedagogical tone and considerably large wall texts offer viewers a sustained sociocultural analysis of the granted works. Though its educational intentions and sizable wall texts sometimes seem to overshadow the actual work displayed, Art and Appetite nonetheless provides a fascinating portrait of American history while considering the usage of food as a conceptual motif throughout American art history.

After passing introductory texts describing the Art and Appetite’s relevancy to Chicago, viewers enter a striking red room that contains four American Thanksgiving-themed paintings. The backdrops to these four seasonal paintings are four painfully red walls, almost the color of emergency signs. This initial room seems to be in many ways a heavy handed way to introduce the viewer to concepts about American painting, culture, and cuisine. Dead center is Norman Rockwell’s Freedom From Want (1942). In this painting the presumable father figure is placed apex at the head of an upper-class, white, family gathering. Animated family figures surround an elderly woman and place a turkey before the father. Their lively frozen gestures, typical of Rockwell’s acute style, propose a populist image of American life in the 1940’s. One who relishes in this constructed nostalgia may also find similar sentiment in Doris Lee’s cartoony Thanksgiving (1935). In this painting several maids bustle around children, pets, and a mother to perform domestic chores. But one who cringes at such American family ideals can turn to the right to find Roy Lichtenstein’s Turkey (1961) and Alice Neel’s Thanksgiving (1965). Neel’s ironic portrait of a turkey, scared and oozing thick red blood into a drain, has repelling details that seem mock the cool and calculated nature of Pop Art, like Lichtenstein’s Turkey, and America’s most gluttonous holiday.

In the next room, the image of Mrs. Ezekiel Goldthwaite stares you in the eyes as one exits the Thanksgiving Room. She sits dressed in the epitome of high-class 18th century fashion against a backdrop of colonial wealth, next to a bowl of luscious peaches. At full scale, painter John Singleton Copley represents the renowned gardener toying with her expert creations in the painting Mrs. Ezekiel Goldthwaite (1771). It seems that the curators intended this room labeled “Horticulture in the Early Republic” to reflect early America’s fertile subsistence farming as a representation of enlightenment ideals in painting. With deep blue walls, the room contains Mrs. Goldthwaite’s portrait and several still life paintings from the Peale family, who were expert horticulturists and painters. As subtly depicted in these Peale Family’s still lifes, each of the paintings gain a larger diversity of crops as years progress. These almost photographic depictions of a variety of fruit seem to evoke the Enlightenment influenced confidence for human capabilities and the prosperity of a new nation in the 18th century.

The next two rooms pair well together as the American “Republic” grows in both age and industry. Dirt brown walls enclose the gallery ‘Parties Picnics and Feast’ to remind the viewer of the all too American longing for the outdoors during a time when “Manifest Destiny” ideals were nationally promoted and Thoreau and Emerson were publishing work. Thomas Cole’s A Pic-nic Party (1846) encapsulates transcendental principles in a roughly 6 by 4 foot frame by representing an upper class dining retreat to a vast mountainous area. To the left of Cole, Francis Edmond gives us America’s earliest painting of a patron eating at inn or tavern.

Alongside the exhibition’s display of paintings, it also featured some memorabilia and artifacts from the development of the commercial food industry in the U.S. In the book Art and Appetite, Barter states that “until roughly the civil war era restaurants did not exist” and as the country made economic developments in travel and trade, dining spaces in early railways and hotels even became necessary. Two titles describe the next larger tan green room, “Dining Room and Antebellum Abundance” and “Temperance Drinking.” In a clear display case, menus from the very first American restaurants start the viewer’s circular movement around grandiose still lifes. These eclectic traditions appear in the period’s growing food industry, and in large scale still lifes depicting countless varieties of fruit. In an undeniably Dutch style, the paintings of this room create sense that America was beginning its track towards the vast “melting pot” of cultures that it is today, with diet and painting as testimony.

Like the Dutch masters of the early Enlightenment, the American painters shrank the size of their canvases during the Gilded Age. The wall text under the title “Modest Meals in the Guided Age” explains how in the late 19th century consumerism had grown tremendously to the profit of families like the Rockefellers, Carnegies, and Vanderbilts, while slums were becoming more and more crowded in urbanizing America. Artists of the time, like those shown here, reacted to this economic disparity and hardship by down scaling still lifes in both subject and size.

For some viewers, the naturalistic still lifes of the first four rooms may start to blend together and become tiresome. After experiencing this extensive collection of naturalistic painting and a room of trompe l’oeil works, the mood and walls lighten from dark purple brown to the light blue as viewers enter the Impressionism section. On the right is William Glackens’s At Moniquin’s (1905). Glackens gives us a famous attorney and his mademoiselle sitting in New York’s most popular French restaurant. The restaurant reminds the viewer of the America’s upper class who found a new appreciation for European dishes, paintings, and nightlife.

With the same light blue walls, the next room holds paintings of the dynamic experimentation that occurred between the first two World Wars. In the 1920’s, pioneer musicians like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington expanded on previous ideas of Jazz with a new emphasis on improvisation in clubs where open defiance of prohibition laws were the norm. This new epoch crossed previous boundaries of racial, sexual, and musical conformity to brew a speakeasy counter-culture that is depicted in the subject matter of these paintings and the designed cocktail sets of this room. Archibald Motley’s Nightlife (1943) strikes the viewer immediately because of its violet hues, which pulsate from an African-American nightclub. Motley, an alumnus of SAIC, initiates in paint what the civil rights movement and enfranchising movements demanded in action. This growing opposition to the Anglo-Christian right, from organizations like the Feminist Flappers, Catholic drinkers, or Black Artists, remind us of the upheaval of social traditions experienced during some of history’s most violent and life-consuming warfare. Artists like Ellington and Motley respond accordingly in their own artwork. In Motley’s work, busy figures crowd the dance floor, which highlights the excitement of this rising liberalism. In a similar “cabaret life” energy, the artists Stuart Davis, Gerald Murphy, and Preston Dickerson paint unmistakably American compositions with a touch of Cubist-inspired compression. These compositions are clean and linear, with an aesthetic derived from commercial advertisements.

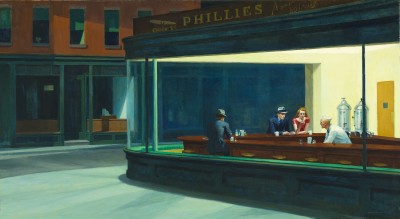

Edward Hopper. Nighthawks, 1942. Art Institute of Chicago. Friends of American Art Collection. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The energy of advertising in America falls away with the next room’s transition to light grey-white walls. Hopper’s classic painting, Nighthawks (1942), is front center to change the mood from Jazzy eclecticism to isolation in Modernity. Like the shrinking of canvases in the Gilded age, it seems some American artists responded in contradiction to mounting sky scrapers and growing food industries with more intimate scenes of domestic life. Many of the paintings in this room are similar in their longing for a familial space in opposition to the commercialization of the 20th century.

Exiting this room the viewer enters the contemporary American art world by experiencing the sparse gallery items and large empty spaces of the second floor of the Modern Wing. The largest room of the exhibit holds a series of artists who each critically worked with imagery from America’s commercial landscape. Considering the lineage of American history represented at the show thus far, Warhol’s repeating soup cans or Oldenburg’s eight-foot wide cloth egg, seem all too appropriate for postmodern artistic reactions. The other pieces in the vicinity continue this ironic depiction of capitalism and materialism with a focus on food and consumption. The inclusion of this room probes viewers to consider how far America has come, from still lifes and subsistence farming to questioning consumerism and capitalism, as they enter the gift shop to conclude the complex portrait of American painting.

Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine provides viewers with a very educational and in-depth sociocultural analysis of each painting. The large wall texts that are paired with each of these works are almost larger than every painting. Though it may prove to be a distraction from the work itself in some cases, it also leads viewers to consider the show not only as a collection of America’s greatest art works about food, but also as a portrait of America through the lens of artistic production.