Sullivan Galleries provide unique opportunities for students and faculty members to explore what it means to be modern.

By Jennifer Swann

Stepping into the new “Learning Modern” exhibition at SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries feels strange at first. Other than the boldly painted columns around the room, the space is almost completely unobstructed by the walls and partitions that are usually installed in a gallery. Instead, the exposed ceilings and giant Chicago windows overlooking the 0, 0 point of the city’s grid open up the space and enable conversations between the city’s architecture and the artworks in the exhibition.

Stepping into the new “Learning Modern” exhibition at SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries feels strange at first. Other than the boldly painted columns around the room, the space is almost completely unobstructed by the walls and partitions that are usually installed in a gallery. Instead, the exposed ceilings and giant Chicago windows overlooking the 0, 0 point of the city’s grid open up the space and enable conversations between the city’s architecture and the artworks in the exhibition.

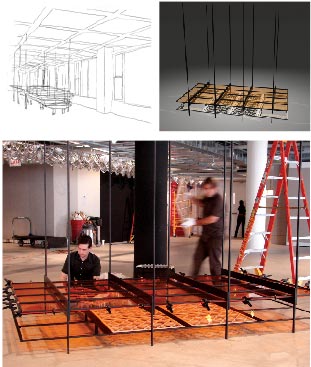

“Key Notes,” a work by Narelle Jubelin and collaborator Carla Duarte, is a text and textile-based installation that specifically responds to the city outside the windows of the Sullivan galleries, in homage to Mies van der Rohe and his collaborator Lilly Reich. The multi-colored planes of fabric respond to the three-part Chicago windows, and at different points in the day, one can see transcriptions of modernist texts reflected through the window and into the fabric.

SAIC Painting and Drawing Adjunct Professor Kay Rosen also uses color and language to respond to the interior structure of the Sullivan Gallery itself. In a work titled, Divisibility, she labels each column in the space with a color and a letter, creating a checkerboard pattern that spells Divisibility from either side of the gallery. The work revisits a painting the artist did in 1984 by the same name, the I’s re-enacting the meaning of the word by physically dividing the consonants. In her painting Black to White, Left to Right, Front to Back, Rosen draws attention to the architectural columns that do in fact divide the space, which was designed by Louis Sullivan for commercial retail, most famously, Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company. The visual linking of the letters in the word “divisibility” ironically create an indivisible dialogue throughout the gallery. Strangely, by pointing out the division enacted by the columns, the piece actually acts to unify the space.

Also responding to the interior structure of the Sullivan Gallery, this time in the form of the exposed air conditioning and ventilation system, is Walter Hood’s Bio-Line, a sculptural metallic form woven across the length of the ceiling, in which groups of Rhipsalis plants contribute to and appropriate the functions of the air filtration system.

Stationed in the center of the gallery is a curious 9’x 9′ blue box that looks more like a homemade spaceship than a piece of modern art. In fact, Knowledge Box was constructed after the original 12’ x 12’ Knowledge Box by Ken Isaacs at the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1962, and functions today as a kind of time machine into the beginnings of modernity. Knowledge Box utilizes the modern, but dated technology of slide-projectors and wireless headphones to encapsulate the viewer within the aural and visual space of the modern era.

Stationed in the center of the gallery is a curious 9’x 9′ blue box that looks more like a homemade spaceship than a piece of modern art. In fact, Knowledge Box was constructed after the original 12’ x 12’ Knowledge Box by Ken Isaacs at the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1962, and functions today as a kind of time machine into the beginnings of modernity. Knowledge Box utilizes the modern, but dated technology of slide-projectors and wireless headphones to encapsulate the viewer within the aural and visual space of the modern era.

Inside Knowledge Box, the viewer is subjected to the rapid-fire clicking off of historical images from Life and Time magazines and audio from accompanying news broadcasts. Portraits of Nixon, Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Sinatra, and other immediately recognizable figures are projected onto the walls, floors, and ceilings, collaging the interior space of the box so much so that one can never fully view all the images at once.

Like a blinking eye, the lens of the slide projectors forces the viewer to associate him or herself as both the observer and the participant, the spectator and the subject. The Knowledge Box is immersed in the idea of modern media and technology; stepping into the Knowledge Box in 2009 compels the viewer to think about the ways contemporary media and technology have changed and expanded since.

Like Knowledge Box, so many of the works that make up the exhibition are experiential, immersive, and didactic, or as curatorial assistant Joe Iverson puts it, “prototypes for a learning tool,” hence the title of the exhibition. Indeed, the space at times feels more like a science museum, or dioramas from Disneyland’s Tomorrowland, than a typical Sullivan Gallery installation. Even AIADO faculty member Charles Harrison’s charming and stylized designs for sewing machines and View-Masters are innovatively pedagogical.

Objects and environments in this exhibition that may at first seem uninviting and foreign reveal after examination deep intricacies and wonderful complications that delight and inspire. Thom Faulders Studio’s Ames Spot, for example, resembles the inside of a birthday cake, with its waves of pink and white frosting; it is only upon exiting the room that one becomes aware of the wall projection that reveals the design phenomenon that creates the unbelievable distortion of perception within the room.

The openness of the gallery’s floor plan and situation of works can seem isolating, but is meant to invite interaction and collaboration, not only between the viewer and the work, but also between the works themselves. Though constructed independently of one another, works like Angela Ferreira’s Crown Hall/Dragon House (2009), a sculpture that replicates, minimizes, and inverts Mies van der Rohe’s architectural structure of IIT’s Crown Hall athe one nd Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s Always After (The Glass House) (2006), a video documenting and romanticizing the clean-up of shattered glass from the window panes of Crown Hall, seem to communicate with one another.

Iverson notes that the exhibition, which took two and a half years to curate, represents “many moderns,” including but not limited to, modern architecture, design, psychology, media, technology, art, and science. The varied works in the exhibition, though challenging and abstract at first glance, are all re-imaginations and translations of modern concepts that beg to be responded to and reinvented again and again.

Students and faculty can propose their own projects for “Learning Modern,” which runs through January 9, and whose subject matter and artists extend to “Modern Monday” gallery talks, the Visiting Artists Program, Conversations at the Edge, and the SAIC course curriculum.

(botom) Jubelin in collaboration with Carla Duarte, Key Notes, 2009. Installation

photograph of Narelle Julin transcribing text onto the Chicago-style windows

of the SAIC Sullivan Galleries. Footnotes and figures (on windows) from: Alain

Findeli, “Moholy-Nagy’s Design Pedagogy in Chicago (1937-46),” Design Issues

v. VII, no. 1 (Fall 1990), pp. 5-19. Photo: Carla Duarte.

High up in space, satellites are keeping constant watch over Earth and relaying data, and astronauts .