The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York reopened its “Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and Later South Asia” (herein referred to as ‘the Islamic galleries,” even though it is neither wholly Islamic, nor Arabic) on November 1, 2011, after eight years of restoration.

As someone who isn’t an Islamic art historian, I take the liberty of not being critical of the titles, mis-titles and other such minutia. I found the exhibition itself to be immaculate: thorough, delicate, fascinating. The extensive museum wing, which houses 15 galleries, is crafted with careful aesthetic and cultural consideration – the doorways are arched and some display hand carving in the paneling. The Alhambra-like “Moroccan Court” (carving done by artisans in present-day Fez) shows the arabesque wondrously, weaving together architecture and space.

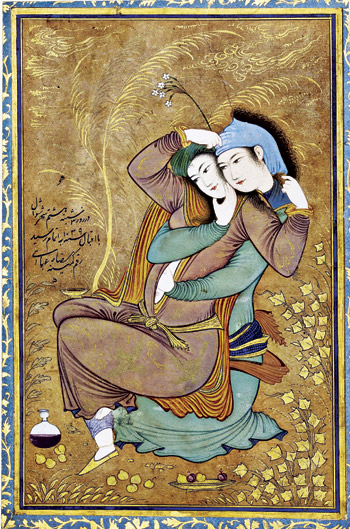

Like a moth, I indulged in the copies of the Quran on silk and paper throughout the galleries – both as full texts or as separate pages displayed to show various writing styles. In other rooms, manuscripts were shown behind glass, their heroes depicted in throngs of battle, intrigue, or in a lovers’ erotic embrace; shadow-less and framed with gold, they were floating against lavender skies and on turquoise grasslands. Along similar aesthetics were the illuminations of the journeys of Muhammed from 16th century Uzbekistan, the beautiful Iranian “Shahnama” (Book of Kings) and the gold-speckled “Mantiq al-tair” (Language of the Birds) from 15th century Afghanistan. Among the many treasures, I was overjoyed to discover a page depicting a hunting scene from Rumi’s book of poetry – Masnavi of Jalal-ud Din Rumi (15th century Iran) – a Sufi poet whose book (the non-illuminated Penguin Classic version) I keep on my bed-stand.

To many visitors, including myself, the depiction of animals and humans came as a surprise. There are six representations of the Prophet Muhammad in the exhibition. Indeed, the display of secular Arab culture is as controversial as it is important, and the prominence of the human figure further highlights the lack of essentialism on the part of the curatorial team (headed by Navina Najat Haidar). As the visitor travels across a thousand years of art territory, from Spain to Uzbekistan, the eye is drawn to recurring symbols, geometry laid in gold and the scattered patterns of floral motifs. The curatorial display emphasizes meandering, bringing to light the universal themes of cultural adaptation and aesthetic improvisation.

The most magical room is the Ottoman Carpet Gallery. The dim-lit space displays several palatial carpets on the walls, and the ceiling in a stunning 16th century Spanish woodwork of echoing geometric forms. The center-piece is a Mamluk period (1250–1517) Simonetti carpet that runs all the way across the floor.

The Met puts a great effort to carve a decipherable path through all this history. The exhibition commences with the Muslim societies in the 7th century and spans the demise of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century. However, for the first-time visitor, the details of the works are simply too overwhelming. Centuries and countries are swept underneath the intricacies of design.The beguiling novelty of the 1,200 pieces on display, each mirroring and incorporating the other as if into eternal microcosms, lines extending and connecting with the feeling of the infinite – this was my impression after the four-hour tour. For those like me, our shared cultural murkiness turns into a dizzy enchantment. As you spin your way out of the exit through Mughal South Asia, you are amazed to realize there was another entrance into the exhibition altogether. Perhaps this is a curatorial nod of encouragement for a personal, unpackaged assessment of the Islamic and Arab art world – a timely and inspiring invitation to find your own entrance.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

metmuseum.org