The art world floods the lagoon for the largest edition in the 116 year history of the Venice Biennale

All photos courtesy of la Biennale di Venizia

Flying in from London on the early morning groggy-eye to Venice, it should have been obvious that this was not going to be a normal biennale. I, like most sane people, try to avoid these 6 a.m. flights, not so much for the inconvenience, but rather because Ryan Air seems hell bent on having you miss your flight (nota bene, if your passport is outside of the EU you have to have your passport “verified” [disinterestedly glanced at] by the ticket counter at least 40 minutes before takeoff, even if you are already checked in online). Inside the overly vibrant yellow cabin (which I am convinced was designed in consultation with psychologists from Guantanamo so it is impossible to sleep, and hence you are more likely to buy one of the many overpriced items constantly hawked in the aisle) filing into the plane at this unholy hour was a constant stream of blue blazers, a myriad of leather clutch weekend bags, and hip summer dresses. The art world was mobilizing en-mass.

My fellow fliers and I were just a few of the over 20,000 who flooded this resplendent island playground in June – augmenting the population of the city by roughly seven percent in the matter of a few days. As one longtime resident exclaimed while frustratedly navigating the packed lanes, “it’s like Carnival!” – and, following in the footsteps of that Venetian tradition with secluded parties and lavish bacchanals, the 54th Venice Biennale had begun.

The opening of the biennale has traditionally been an extended reunion, oscillating between gatherings and art (and many times intermingling them both). This year, however, there seemed to be a strong undercurrent of superficial spectacle, comprised mainly of being there and being ‘seen.’ Just a few examples: the blogosphere going wild over Roman Abramovic’s new mega-yacht; and Vogue Italy’s continuous coverage of outfits, what celebrities were in attendance, and the ‘it’ tote bag among those handed out by the exhibitions.

This tone was augmented by the Pantagruelian nature of the actual event, consisting of two major exhibition halls, 89 national pavilions, 37 official collateral shows, and then dozens of other talks and performances. But within this sprawling landscape that inevitably stretches the artwork (and one’s attention span) thin, there was still substance to be found in the espresso-and-spritz driven marathon.

Given the enormity of the experience, this article is not meant as a comprehensive review of the myriad of shows, but rather a subjective path through certain works, pavilions and events. The account is split into two parts: the first looking at the main exhibition in the Arsenale; and in the second, the rest of the main section in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, as well as a few of the national pavilions.

The ringleader / artistic director of this year’s biennale is the art historian and editor of Cabinet, Bice Curiger. In a testament to entrenched traditions, her appointment makes it only the second time a woman has held the reins (the first was in 2005, when the 51st edition was co-curated by Maria de Corral and Rosa Martinez). The title, IllumiNATIONS, is a bit of grammatical jest alluding to Rimbaud, Walter Benjamin, a vague notion of community, and the centrality of the more classical notion of light.

Stepping into the Para-Pavilions

The first stop was the cavernous Arsenale – the old shipyard which sustained the city-state’s naval power in the sixteenth century. The entrance is occupied by one of five “para-pavilions,” conceived by Curiger as a means for artists to construct an architectural setting to host other artists. This installation by Song Dong is teaming with rings assembled from the façades of wardrobes, alluding to the practice in working class China of placing wardrobes in front of the often cramped abode to serve as storage. The practice effectively expands the zone of the home, while also turning the domestic space inside-out and blurring the border between public and private.

Song Dong’s architectural arrangement forms part of his ongoing series, “Intelligence of the Poor.” The disorienting collection of vistas and perspectives framing and dislocating space is by far the most compelling introductory piece in the last couple editions of the biennale. Anchoring the center of the maze of circles is the artist’s ancestral home from Beijing. Part of a traditionally one-story siheyuan, the house is complete with a large ‘pigeon coop’ on top – the only permissible way to build a second story addition at the time. Inside the coop was a desk and chair constituting a little study, evidence of the subversive potential of architecture.

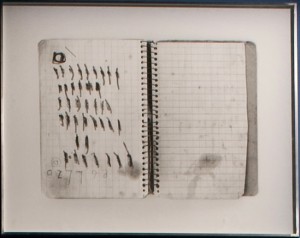

Part of Yto Barrada’s contribution to the para-pavilion is The Telephone Books (or the recipe book) (2011), a series of photos documenting the artist’s illiterate grandmother’s notebook. The book contained a combination of symbols and pictograms, creating a new idiosyncratic language of sorts to represent her children and their phone numbers.

Documents and the Informational Sublime

Yto Barrada’s project, as well as several others, demonstrated that archive fever is still raging. Further on down the vast halls of the Arsenale, the black and white photo series File Room (2011) by Dayanita Singh – a part of Franz West’s para-pavilion – captures scenes in various offices and archives with overflowing stacks of records, cobbled together and loosely forming an anachronistic system bordering on anarchy. These paper purgatories reveal the inherent fragility of the document, and expose the entropy present in any system of knowledge.

Elsewhere, Elisabetta Benassi explores the “backside” of twentieth century history through the descriptions on the rear of iconic photographs that the artist found in the archives of various news agencies. These images whirl by on automated microfiche machines that randomly generate different progressions. The result is a cacophony of political events and popular culture which takes the form of choreographed anarchy. The flow of documents does not subscribe to any overarching linear narrative; rather, the movement allows events to constantly shift in proximity to one another and generate new readings.

Continuing in the vein of re-examining historical narratives, the two-channel video by Mohamed Bourouissa presents a retelling of a clandestine poker game that is suspected of being rigged. Interviews with the participants and footage of the event itself provide multiple perspectives and varied accounts. Reminiscent of the editing strategies employed by Harun Farocki, the players are invited to watch the footage documenting the event and comment on the action, individually describing the scene and their involvement. This self-reflexive act casts doubt on the veracity of the images, and highlights the act of viewing itself.

A Wider Spectrum

Rising around one of the bare masonry columns in the Arsenale was Fabian Marti’s totemic The Summit of It (2011), a fiberboard cubist construction adorned with collapsed ceramic vessels that are linked with tape, and arranged around the various platforms of the structure. The interior of the construction (a domineering geometric niche) was lit by a rectilinear projection of the sun, footage that was captured during the Islamic call to prayer on an iPhone 4 (the use of the iPhone was conspicuously noted). The mis-en-scène creates a certain spatial and geographical transformation, while the intimacy provides much needed relief from the uniformity of the rest of the Arsenale.

Curiger included a number of works that focus on the examination of the image through color. Nick Relph intertwined three documentaries – the story of the Scottish fabric, tartan; a documentary on Ellsworth Kelly; and a profile of the designer Rei Kawakubo, the founder of Comme des Garçons. Each film was projected from one of three massive CRT projectors that occupied the center of the room, appearing one on top of the other, each filtered through a different color. The overlay of images and the soundtracks functions like the technological representation of the tartan; composed of multiple colors that are combined in various patterns while still retaining their own space, the films create a sort of electric-kool-aid-acid-test heterotopia.

While the photographs of Elad Lassry show his deep admiration for Christopher Williams (a fellow product of Los Angeles area art schools), his 35mm film Untitled (Ghost) (2011) draws instead on the early practitioners of cinema, such as Georges Méliès. In both mediums, a distinctive notion of color emerges, one that treats color as an actor, co-existing with the other elements and possessing the potential agency to transform/alter/influence the scene.

Time for the Lion

The Clock (2011) by Christian Marclay is conveniently located at the end of the quarter-mile long hall, surrounded by inviting sofas for the weary masses. The piece consists of a montage of films that include scenes where time is evident – for example, checking the wrist watch in Run Lola Run, or Richard Hannay clinging to the minute hand of Big Ben as he tries to prevent a bomb from detonating. Marclay synchronizes the cinematic time with the viewer’s time over the course of 24 hours, so that one can literally watch time pass through the compilation of scenes. At its very core, the gesture of matching these times reveals the essence of the diversion of film — as opposed to being transported to another time, one becomes constantly aware of time itself passing, and by contrasting these two times, the act of viewing itself comes into focus. This effect ultimately approaches Dziga Vertov’s aspiration for a cinema that is able to “decode life as it is.”

Overall, the exhibition design of the Arsenale was well modulated and paced, the continuous ancient hall divided into manageable rooms (large white cubes, in essence) that create a certain comfortable rhythm akin to a museum-like experience. While Curiger is not the first to implement a more institutionalized space (both her predecessors Robert Storr and Daniel Birnbaum also opted for more controlled environs) her biennale seemed to move away from the idea of creating a site of production or experimentation, and toward a notion of collecting. Most of the works in the show had been exhibited previously, including the Golden Lion-winning montage by Marclay, and at times it felt as though one was witnessing the classical concept of a biennale – a nice gathering of highlights from across various art hubs, brought together in a holiday destination for the enjoyment of the visiting masses. Viewed from the cramped streets of Venice during the opening, it would appear that the strategy of not rocking the boat is what keeps everyone coming aboard.