This article was uploaded to a longer web version on 1/27/2025

An email popped up in the inboxes of students and faculty at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on Oct. 30 that seemed a little out-of-the-ordinary. The subject line read, “Part-Time Faculty Union: Where We Stand On Negotiations,” signed by Martin Berger, provost and senior vice president of academic affairs, and Alexandra Holt, executive vice president for finance and administration. It came amid whispers of a potential strike by the Non-Tenure Track faculty members at SAIC in response to what NTT faculty members said they consider an unusually slow pace for bargaining negotiations.

When asked about the timing of the email, Berger said, “Given that the union raised the possibility of a strike for the first time, we thought it an appropriate moment to ensure that staff, students, and parents had accurate information about the School’s bargaining position.”

The email by Berger and Holt outlined the school’s economic proposal presented to the Art Institute of Chicago Workers United, addressing the primary concerns shared by the union. These included the following: a new healthcare stipend, guaranteed salary increases, longer contract lengths, elimination of promotion or leave prerequisites, and return of course guarantees. While some items lacked specifics, like the amounts for the new healthcare stipends, others were less ambiguous.

Speaking to the guaranteed salary increases, the email said the school would agree to “a more than 10 percent increase in course rates for all part-time faculty members,” with the caveat that this would be made actionable over the next four years.

According to the most recent NTT proposal guide, the primary demands pertain to access to health care; job stability; a three-step grievance process, ending in third-party arbitration; and pay parity with full-time faculty.

Referring to job stability, the NTT proposal addresses layoff requirements and states, “Layoff proposals include providing enough notice and compensation so that losing one or more courses would not be catastrophic.”

Addressing access to healthcare, the proposal states, “Health insurance is NOT a merit-based issue.” As supported by the Federal Law and Affordable Care act, the proposal states that faculty should not have to choose between going to the doctor or paying rent.

The grievance and arbitration process put forth by AICWU’s proposal addresses recourse for violations of the union contract. For instance, as it stands now, the administration has the ability to terminate or not reappoint any NTT faculty for any reason. AICWU has proposed that termination would require “a good and legal reason — for any such acts.”

In the summer of 2020, the museum and the school laid off 150 staff and faculty members. These layoffs were reportedly executed without discussion or warning.

Pay parity refers to equal pay for equal work. According to AICWU’s proposal, “We used the MLA Recommendation on Minimum Per-Course Compensation for Part-Time Faculty Members as a starting point to negotiate Per Course Rates (PCRs), but we won’t accept anything less than parity.”

The email from Berger and Holt was sent shortly after the AICWU NTT faculty held an event at a park across from the 280 Building, since they were not permitted to gather on campus to share updates.

“[The administration] did not share what was happening in bargaining in a truthful manner, or obfuscated it a lot,” said Sarah Bastress, a lecturer and a member of AICWU.

Anjulie Rao, a lecturer and AICWU organizer, said that many of her students had approached her for clarification, as the content of the email was confusing.

There are three primary bargaining units under the AICWU umbrella. These include staff at the Art Institute of Chicago, staff at SAIC, and NTT faculty at SAIC.

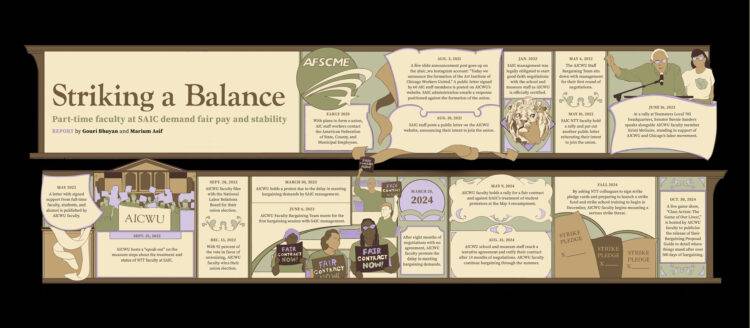

AICWU faculty and museum staff negotiated their first contract with the AIC administration in August 2023, following 14 months of discussion. The NTT formed its bargaining team in April 2023 and began negotiations in the first week of June 2023. They are now 18 months in and are still bargaining.

“You can’t run a place where between 70 and 80 percent of your classes are taught by folks like me, and refuse to pay us a basic living wage, refuse to insure us, and refuse to give us any path towards stability or promotion, because you deem us interchangeable and disposable,” said Kristie McGuire, administrative assistant of academic operations and an AICWU bargaining committee member.

Berger pushed back on the suggestion that SAIC does not fairly compensate part-time faculty. He said, “SAIC currently offers the second highest per course rates of any [Association of Independent Colleges of Art & Design] school, along with robust benefits, including a health care benefit for the almost 200 part-time faculty who have the rank of adjunct.”

While the administration has direct access to the student body and staff, the union only has contact within the NTT faculty pool and the full-time faculty and students who have interfaced with them previously.

According to calculations done by the NTT unit of AICWU, it takes two to three tuition-paying students per class to compensate for the instructors’ pay. The smallest class size at SAIC has eight students, with the largest at over 30 students.

Berger said that tuition goes to covering more than faculty salary. He mentioned the cost of janitorial services, security, staff in the DLRC, Wellness Center, the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Office and more. “All of these offices — and their attendant costs — are needed to support each class,” Berger said.

“When the school tries to pit paying the NTT against raising student tuition, that is an absolutely false pairing,” said McGuire. McGuire said that hours spent working out of class for work-related tasks such as mentoring and writing letters of recommendation are not clocked.

“The raises they are offering us will still result in a pay cut once adjusted for inflation,” said Bastress.

On salary increases, Berger said that most U.S. higher education institutions do not factor inflation rates into compensation.

New research by the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources found that the median pay raises for employees of most higher education institutions in 2023 to 2024 “continued the upward trend seen last year (and exceeded the inflation rate for the first time since 2019 to 20).”

Bastress also highlighted how the contract affects everyone, noting that a large portion of the faculty are alumni and some current students will move on to join as faculty eventually. She expressed feeling disrespected not only as a faculty member but also as an alumnus.

Bastress added that the NTT faculty are often left in the dark about their course assignments until just weeks before the semester begins. She said that, like many of her colleagues, she is forced to rely on side gigs to maintain financial stability.

Last year, the part-time faculty at Columbia College Chicago went on the longest adjunct strike in U.S. history. This 49-day strike shed light on how higher education institutions in the U.S. have been increasingly relying on adjunct faculty who have little to no job security and low pay.

Following suit, in spring 2024, AICWU faculty began to mount a serious strike threat by asking NTT colleagues to sign strike pledge cards.

“Most of the team members started teaching because they care about student education,” said McGuire. Bastress, Rao, and McGuire all agree that a strike would be destabilizing for faculty and students. NTT faculty members signing the strike pledge are concerned about going unpaid for the duration of the strike. A priority for AICWU faculty members is to raise a strike fund to financially support faculty members during a potential strike. Research for this fundraising has been ongoing since April 2023.

“We’re making sure that we’re raising funds so that people are financially supported,” said Rao.

“Our offer to the part-time faculty strives to balance our desire to offer them a fair contract with our obligation to provide students with an excellent and accessible art and design education,” Berger said.

There is no expectation on the part of AICWU faculty members for students to get involved in the strike. However, often, students do get involved in faculty unionization efforts worldwide.

When asked how students were approaching the potential strike, Mira Simonton-Chao (MAAE 2025) said that the past year had demonstrated the need for the community to unite in order to get the administration’s attention.

“One strategy that other schools have used successfully is organizing tuition strikes, and I definitely think that could be an effective approach at SAIC, along with generally building campus solidarity,” said Simonton-Chao.

(A tuition strike is a form of protest where students refuse to pay tuition fees in order to demand changes in policies, practices, or financial transparency.)

It’s important to have conversations with families or folks financially supporting our education to raise money for the strike and hardship fund,” said Nao Goldstein (BFA 2027).

Across the world, students have supported faculty unions as they prepared to go on strike. In the United Kingdom, over 70,000 students signed a petition demanding universities to pay them for loss of class time when the University and College Union went on a 14-day strike. More than 1,700 students from the University of Auckland led a petition in support of their faculty union to support their pay raise in 2022.

At SAIC, faculty and students have often stood in solidarity with one another. Just this year, SAIC faculty issued a letter in support of the May 4 protestors, many of whom were students. AICWU then released a statement echoing the demands of SAIC student protestors.

“If I was a student, I would be concerned if I was being taught by faculty that is perpetually exhausted and underpaid,” said McGuire. Both McGuire and Bastress iterated that given how tuition-dependent SAIC is, students hold an immense amount of power and agency.

“[Students] should ask questions, they should be talking to their professors. Sometimes when you’re faculty and you’re teaching one class, it’s really easy to feel like you’re not really a part of the SAIC community. Having students express any type of support for this builds a sense of togetherness,” said Rao.

The NTT faculty said they feel confident that, based on the support they are seeing, they have a strong base of colleagues ready to take action if needed.