Human activities since the Industrial Revolution, both in terms of technologies and agriculture, amplify carbon dioxide emissions — one kind of greenhouse gasses. In the face of global warming, rises in sea levels, and the melting of ice caps, alongside other man-made disruptions like deforestation, mining, fracking, and pollution, people have been living in a time of eco-anxiety. Seeing the potential healing power of arts, both artists and curators have been examining ways to inspire actions and thoughts to mend the environmental impacts created.

Sharmila Wood — a Western Australia-based independent curator who investigates social change, history, and ecology in design and art — curates “Actions for the Earth: Art, Care & Ecology,” a traveling exhibition that is currently on display at Northwestern University’s Block Museum. Wood’s curation “considers kinship, healing, and restorative interventions as artistic practices and strategies to foster a deeper consciousness of our interconnectedness with the earth,” according to the curatorial statement.

This exhibition is produced by Independent Curators International (ICI), New York, and coordinated by Chicago-based consulting curator Stephanie Smith, who curated “Beyond Green: Toward a Sustainable Art,” a touring exhibition started at Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago in 2006.

Wood curates a highly diverse survey that features both international and intergenerational artists. Time-based media — like sound, video, and web-based arts, frequently marginalized genres among galleries and museums — populates this exhibition.

Several works encourage visitor engagement and highlight interactivity. Katie West (b. 1988, Australia), a Yindjibarndi artist based in Noongar Ballardong country in Australia, interweaves a meditative space with her signature textile installation. She uses naturally dyed fabrics in her work “Clearing” (2019), which brings forth the color and scent of certain native plants into the gallery space. The suspended fabric spans almost the entire gallery on the first floor. With this shelter-like structure, West lays out various cushions for visitors to meditate on.

Compared to its previous iteration in TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville, VIC as a commissioned work, the former site invites a significant amount of natural light into the museum. In contrast, the first-floor gallery in the Block Museum does not cater to these formerly existing elements. Accompanying the installation is a score composed by Simon Charles with a spoken score by Katie West. The sound component, however, was interfered with surrounding ongoing conversations by student staff in the area during the visit. This experience raised my attention to how a space and setup should be accommodated to maximize the audiovisual experience of visitors.

In the same area, there are works by Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016, United States), an early experimental electronic musician and pioneer of deep listening and sonic awareness. Several of her sound works are dispersed through pairs of headphones, which are more effective for a “deeper listening” while background sound is inevitable.

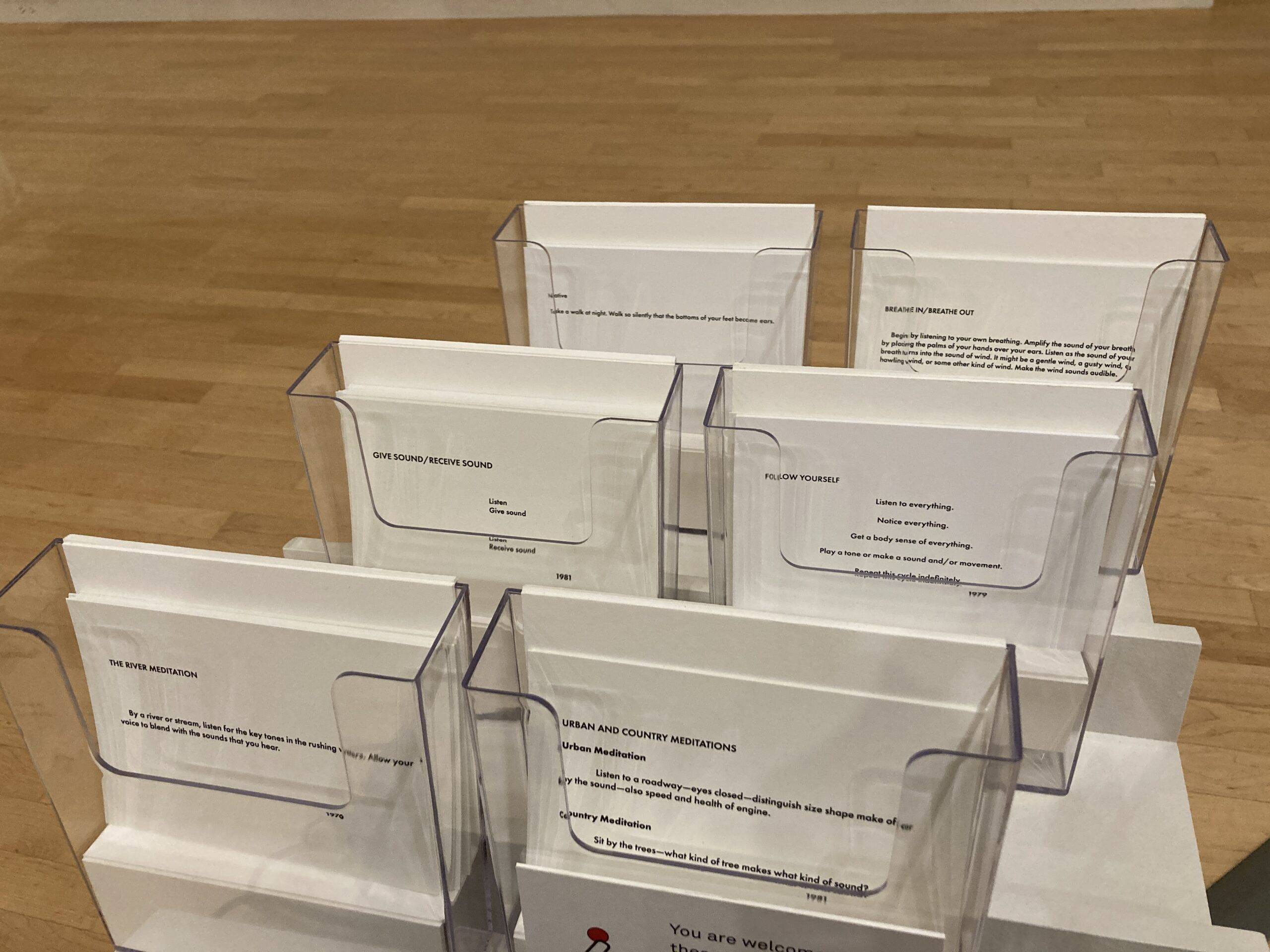

Besides recordings, Oliveros’ six sets of “Sonic Meditation” invite visitors to take away with them and these include: “The River Meditation” (1976), “Urban and Country Meditations” (1981), “Give Sound/Receive Sound” (1981), “Follow Yourself” (1979) “Native” (1971), and “Breathe in/Breathe Out” (1982). “Sonic Meditations” was first initiated in 1971 and was published in 1974 as a short volume. It complies with a series of instructions, text, and scores that reimagine our relationship with sounds. In the “Introduction II,” she writes “Sonic Meditations are an attempt to return the control of sound to the individual alone, and within groups especially for humanitarian purposes; specifically healing.”

These instructive meditations guide readers to pay attention to their surroundings. For instance, “Follow Yourself” notes, “Listen to everything./Notice everything./Get a body sense of everything./Play a tone or make a sound and/or movement./Repeat this cycle indefinitely.” Through this mental aural training, listeners elevate their sensory awareness and state of being.

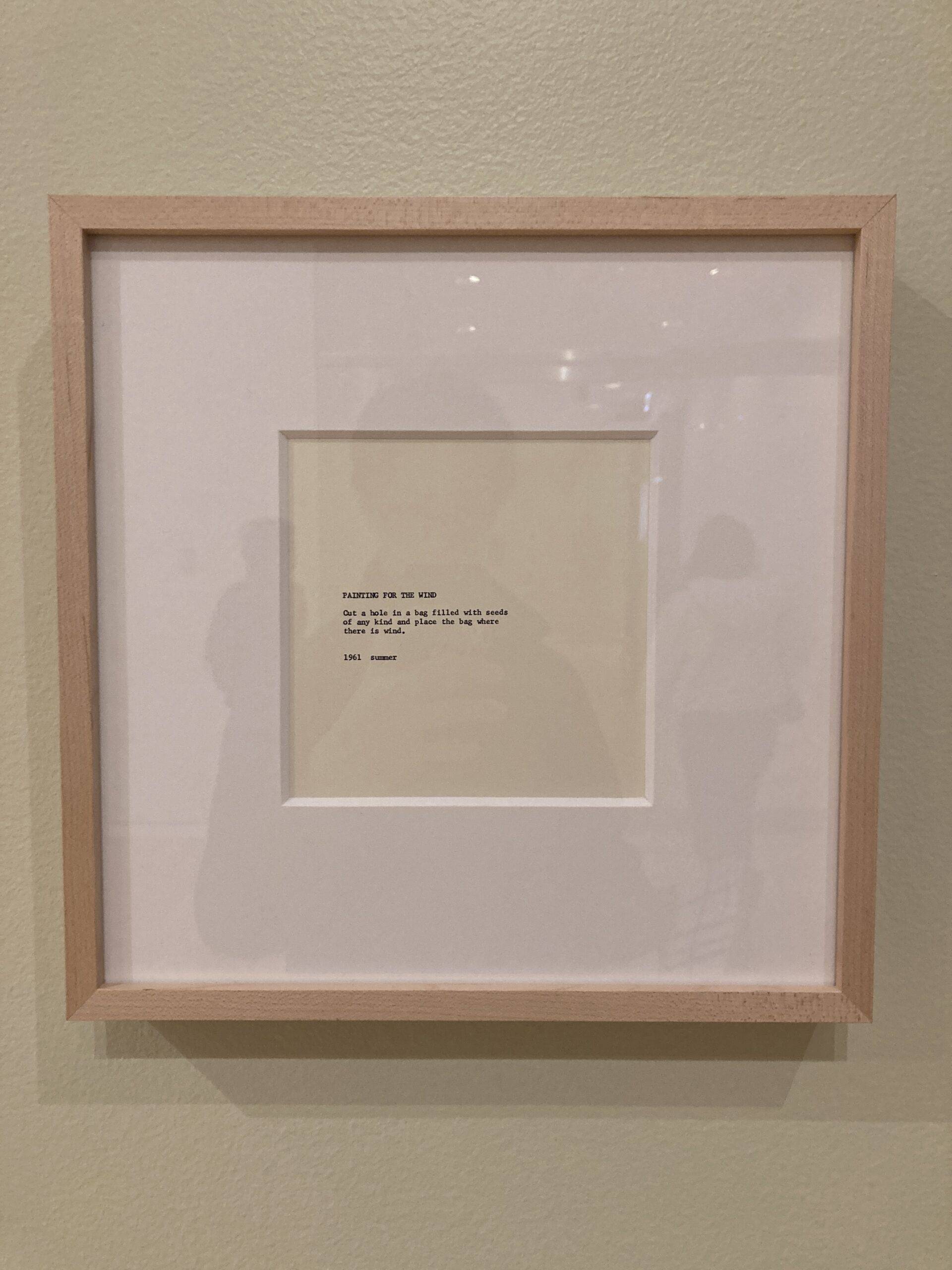

Continuing the narrative of text-based score and mental exercise, Yoko Ono’s (b. 1933, Japan) “Painting for the Wind” (1961), an instruction piece from “Grapefruit” (1964), instructs viewers to “cut a hole in a bag filled with seeds of any kind and place the bag where there is wind.” The conceptual framework, with no right or wrong way to execute, stimulates viewers to examine an action through both physical attempts and mental imaginations.

Echoing the theme of seeds, Chilean multidisciplinary artist Cecilia Vicuña’s (b. 1948, Chile) “Semiya (Seed Songs)” (2015) — a single-channel video work — rekindles connection with earthly lives through her gentle touches and care to endangered native seeds in the Colchagua region. The tranquil closeup reveals the fondness for a deep connection between mankind and nature. As a personal pilgrimage to restoring well-being in nature, the intimate and genuine lullaby-like chant extends its healing power to the audience.

Besides connecting back to nature, Zarina Muhammad’s (b. 1982, Singapore) “Calendrical Systems for the Afterlife” (2022) invites audiences to connect to the spiritual realm. This altar-like mixed media installation includes two standing shelves designed as moveable shrines sitting on top of a round platform scattered with a fuchsia circle of incense. Engaging contributions from audiences, the instructions read, “[P]lease leave a note or object (palm-sized or smaller) that represents this sense of shelter, safety, and sanctuary.”

This way of offering opens up a dialogue not only between visitors and the artist but also between visitors and their loved ones. What strikes the visitors immediately is also the fragrance from the incense in the installation, extending one’s sensory experience. Drawing spiritual practice from multiple cultures, Muhammad creates an inclusive space and portal to welcome visitors to contemplate their spiritual connections.

The inclusiveness of this exhibition in highlighting intercultural and intergenerational representation through a wide range of media is exceptional. It invites visitors to reimagine the power of arts to potentially reconnect us with nature through love, care, and kindness.

To experience more, check out this exhibition at Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University in Evanston until July 7, 2024.