We live in a digiverse. A simulation filled with AI images, newphoria, TikTok trends, algorithms, and content creation. We swipe and like our way through the economy, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic. We live in a physical and digital world of rapid consumption. We are more accustomed to shopping in our pods.

I am casually concerned about the cultural decline of reading. In the winter of 2022, I do my graduate school applications. I have the Beths’ song “Expert in a Dying Field” on blast during this period of my life — because I want to work in books.

Working in a bookstore once, my manager told me while writing recommendations to display under the books, “Don’t write too much. They stop reading after a few sentences.” I write in big letters about a horror novel I enjoyed, “Two Words: Oyster Shucker,” not meaning to be too on the nose, but a handful of copies sold that day and that week.

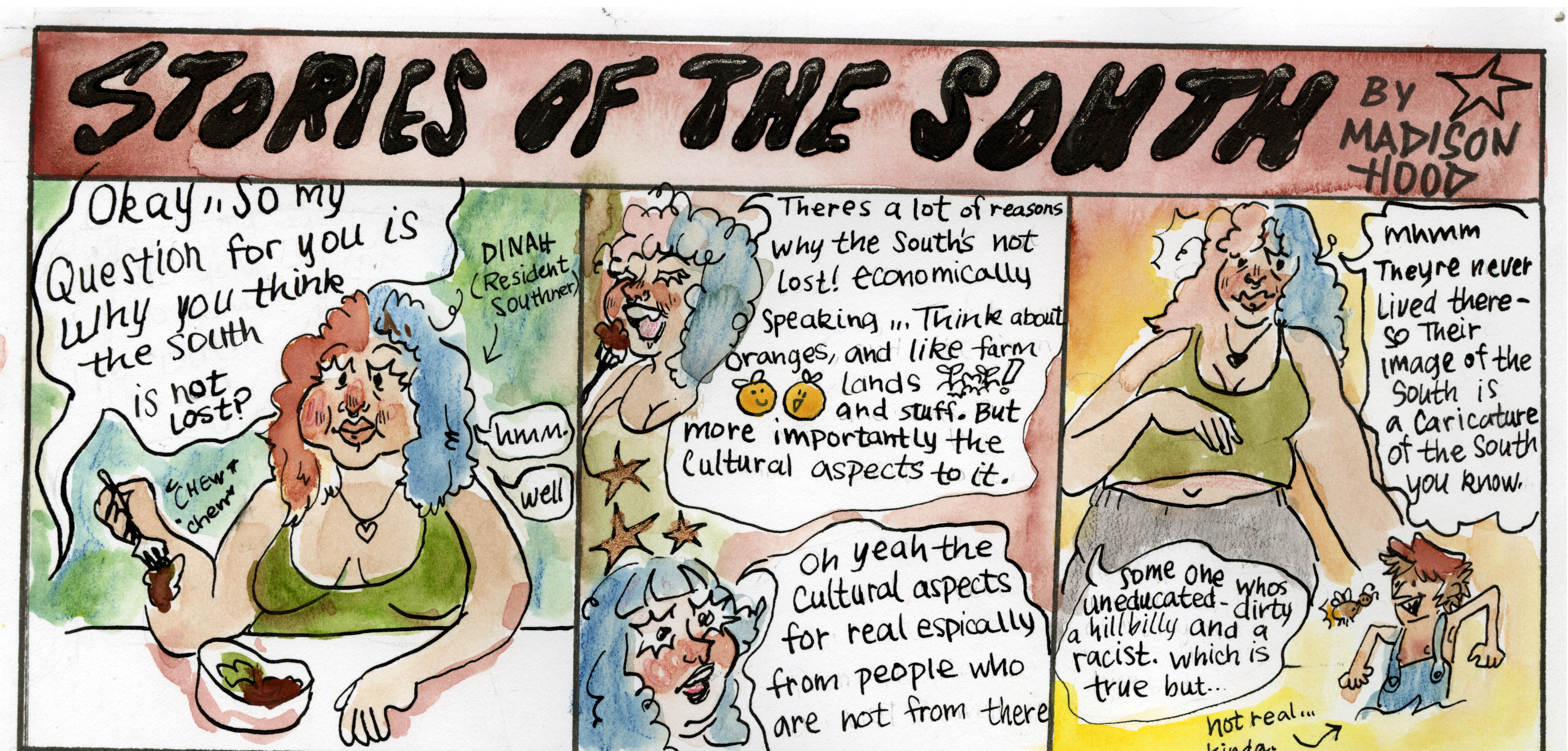

There is such a thing as a “BookTok book,” and it’s a huge deal. Often, books today are made commercially popular through TikTok and Instagram content produced by BookTokers, Bookstagrammers, book bloggers, etc. I’m waveringly confident that Colleen Hoover might be an AI. After all, she came up practically overnight, catapulting into recent literary fame (this internet legend has sold over 20 million books, as estimated by the New York Times in October 2022) after her works went viral on TikTok.

There are whole displays in indie bookstores, the words “as seen on BookTok” scribbled on large paper signs made by the staff. Popular books are also promoted through publishing companies’ and authors’ social media accounts. This shift in marketing also marks a shift in consumer consciousness.

Sometimes, I think of the publishing and consumer book trends exhibited during late-stage capitalism as homogenization. Certainly, the publishing industry is a small club with big members. Five major publishers in America, known colloquially as the “Big Five,” produce and control most of the book media we consume. It’s a big problem when thinking about the future diversity of literature.

At other times, I think of these trends’ close-knit relationship with social media as a form of community, although the digitization of books by the hands of consumers holds within its grasp both possibilities of streamlining and expanding successful literature. It isn’t hard to find someone reading Colleen Hoover on the train, but occasionally indie books that wouldn’t otherwise get the time of day from consumers go viral as well.

There are a few Bookstagram accounts I love. My most bookish friend and I send each other posts of recommendations the other might particularly like. That’s the feature of Instagram I like best: although I dislike the cultural pressure to reproduce a fractal self across the internet, I enjoy the ability to effortlessly and instantly share and engage with content.

Today’s reader has a shorter attention span. Likely it’s because we’ve grown accustomed to the immediacy of digital media like social media, our handheld screens, and TV. “Les Miserables” is shaking in its boots.

Look at the rise of novellas and short novels in recent years that are popular on social media: “The Swimmers” by Julie Otsuka, “Convenience Store Woman” by Sayaka Murata, “Signs Preceding the End of the World” by Yuri Herrera, and “The Employees” by Olga Ravn or the recent recurrent classics “Bluets” by Maggie Nelson and “Autobiography of Red” by Anne Carson, all of which are under 200 pages.

“Ms Ice Sandwich,” published in a crisp white and bright blue paperback with four melting popsicles on the cover (a clean, eye-catching, pop design), rose to relative success in the indie books sphere after the success of author Mieko Kawakami’s other repertoire of books and is only 92 pages.

Short books are in.

These fit-in-your-bag sized books are irresistible. I prefer paperbacks, and sometimes I even select them based on their covers. The phrase “don’t pick a book by its cover,” might not survive, in its most literal sense, a future where covers are designed with mindfulness toward how they might look on stories.

In our consumption-oriented, fast-paced digital culture, it can feel like content is being produced faster than I could ever consume it. The reality, of course, being that it is.

In the notes app of my phone I have a page titled “books I read in 2023,” which is succeeded by five diamond emojis, although this year I made the decision to use robots and aliens. At the end of each year, I choose whether or not to post my favorite reads (this most recent December I decided not to, opting to keep the experience sacred), following another popular trend on Instagram. It’s not that I am prideful, but that I’m eager to consume more and more media.

Short books only take a few hours to read (and short TikToks, for what it’s worth, only take a few moments to watch). Many readers are egotistical, desiring to read more books or more complicated books with the intention of broadcasting their accomplishments to friends or to the internet.

I’ve had this conversation and similar conversations several times in literary circles. It often goes something like this: “I’m trying to beat my reading goals from last year.” “Me, too.” That’s capitalism, for you.

A short journey into the BookTok universe with the search “books under 200 pages” brought me to the most popular lists of short literature I can consume in the most rapid period of time, maximizing the productivity of my literary pleasure. The top post by @alyssaathenaa, informs me that “If you are behind on your reading goal, I have 12 short books, under 200 pages. You can read them in one sitting, and they’re all from different genres.” I also breezed through lists captioned with funny adages like “short books for people with short attention spans. *me, I’m people,” and “short books under 200 pages for my girlies with nonexistent attention spans” by the users @myreadsbooks and @sisiliareads respectively.

Does it mean in the future, when we have all become cyborgs, that reading will be absorbed into consumption? Will our collective late-capitalism hive-mind psyche become part-machine? And will that machine make time for reading? I tend to think of the fear of digital progress as closer to sci-fi than to reality, but I do feel anxious when someone tells me “I haven’t read a book in years.”

Regarding the type of literature we ingest (and in interest of shifting the conversation away from quantity, and towards quality), I’m not sure progress and change is such a bad thing.

Short works are often a foray into hybridity and genre-defying works dabbling readers wouldn’t otherwise select. Both “Bluets” and “Autobiography of Red” break form from traditional narrative structure — “Bluets” in scattered fragments and “Autobiography of Red” in sparkling lines of poetic prose. Both are visions in primary color.

I don’t think short books necessarily have less to say than longer ones, or that no one will read “Middlemarch” in our uncertain robot apocalypse future, but I like short fiction. Take “Violets” by Kyung-Sook Shin, which is over like a dream in 218 pages or “Sweet Days of Discipline” by Fleur Jaeggy which burns until its frustrated conclusion at 101 pages. These books have stuck with me just as much as longer works have, if not more so.

Some of the books on my shelves I know I won’t reread anytime soon, but I could never part with them. They’re like little discs of a consciousness I can input into my brain.

If hope for the future means hopefully in the future there will always be more, then let there be more.

Or, if our future is brief, let it be like some of my favorite books: fast, blazing, 90-page novellas that left lasting impressions on me.