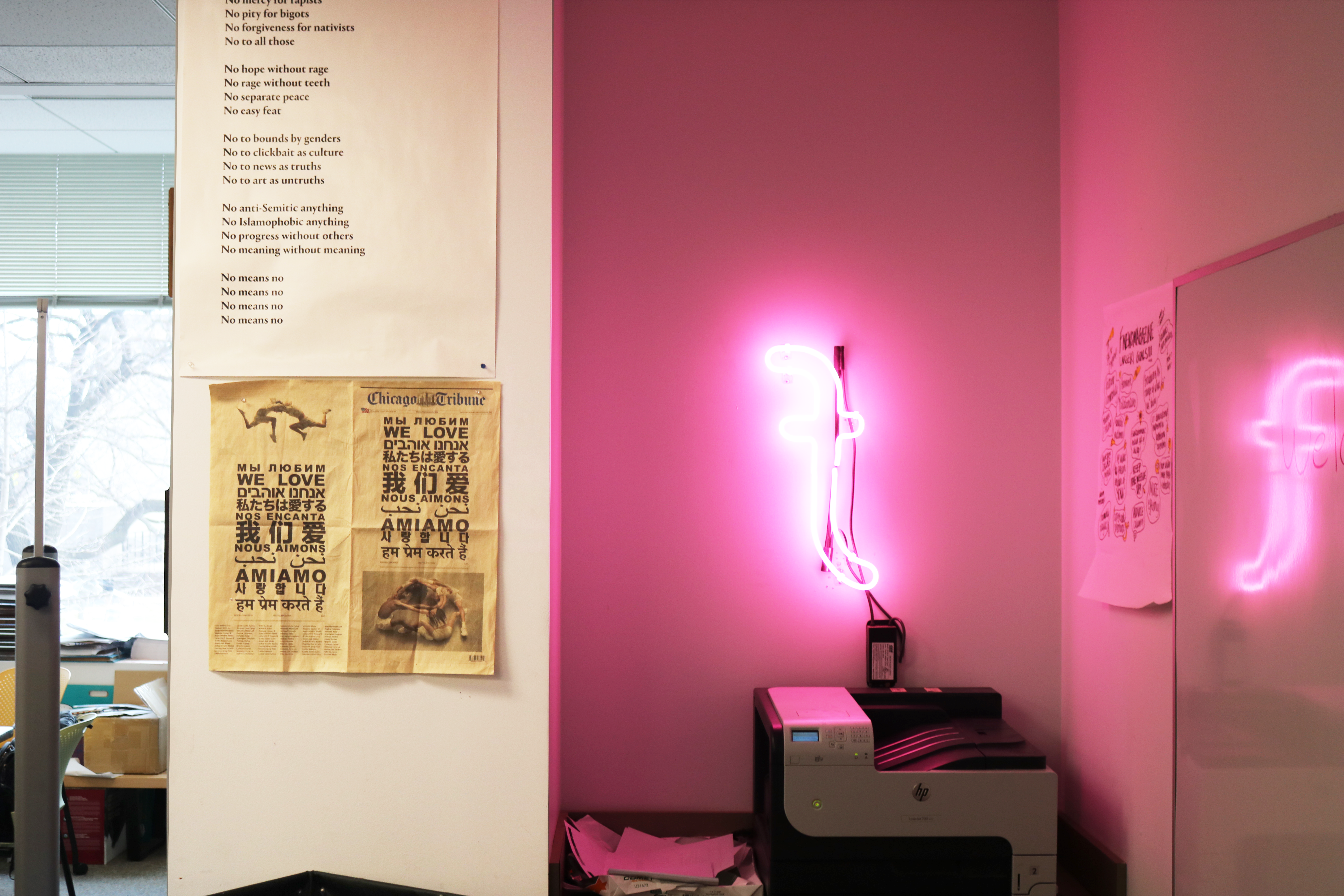

“Graduate Exhibition One” at the School of Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) on March 1 to 8, showcased the multi-disciplinary artworks and skills of 67 graduating MFA students. While many artists in the exhibition worked across media, new media, in particular, was prominent in several artists’ works. To acquire more insight on how artists respond and interpret ever-changing technologies, Gordon Fung, the Arts Editor of the F Newsmagazine interviewed Nimrod Astarhan (MFA ATS 23), Mac Pierce (MFA ATS 23), and Eugene Tang (MFA Photography 23) about their practices.

Interview with Nimrod Astarhan

Q: How do you see technology and media as ways to extend human experience or reality? Do you have any opinion on the recent surge of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-art?

A: The most interesting way media technology and AI are expansive is how they destabilize our existing notions of both media and intelligence. These fields are the most recent ones to adopt an ecological point of view. Media is not merely a means of communication but a living environment — elemental media — entangled with the life forms it enables and is enabled by. Intelligence is not limited to humans. I use media technology to refigure a specific context using speculative digital archeology. I am trying to show techniques for constructing a human experience of history, how history can become a material for art. Other technologies have the potential to be helpful for that.

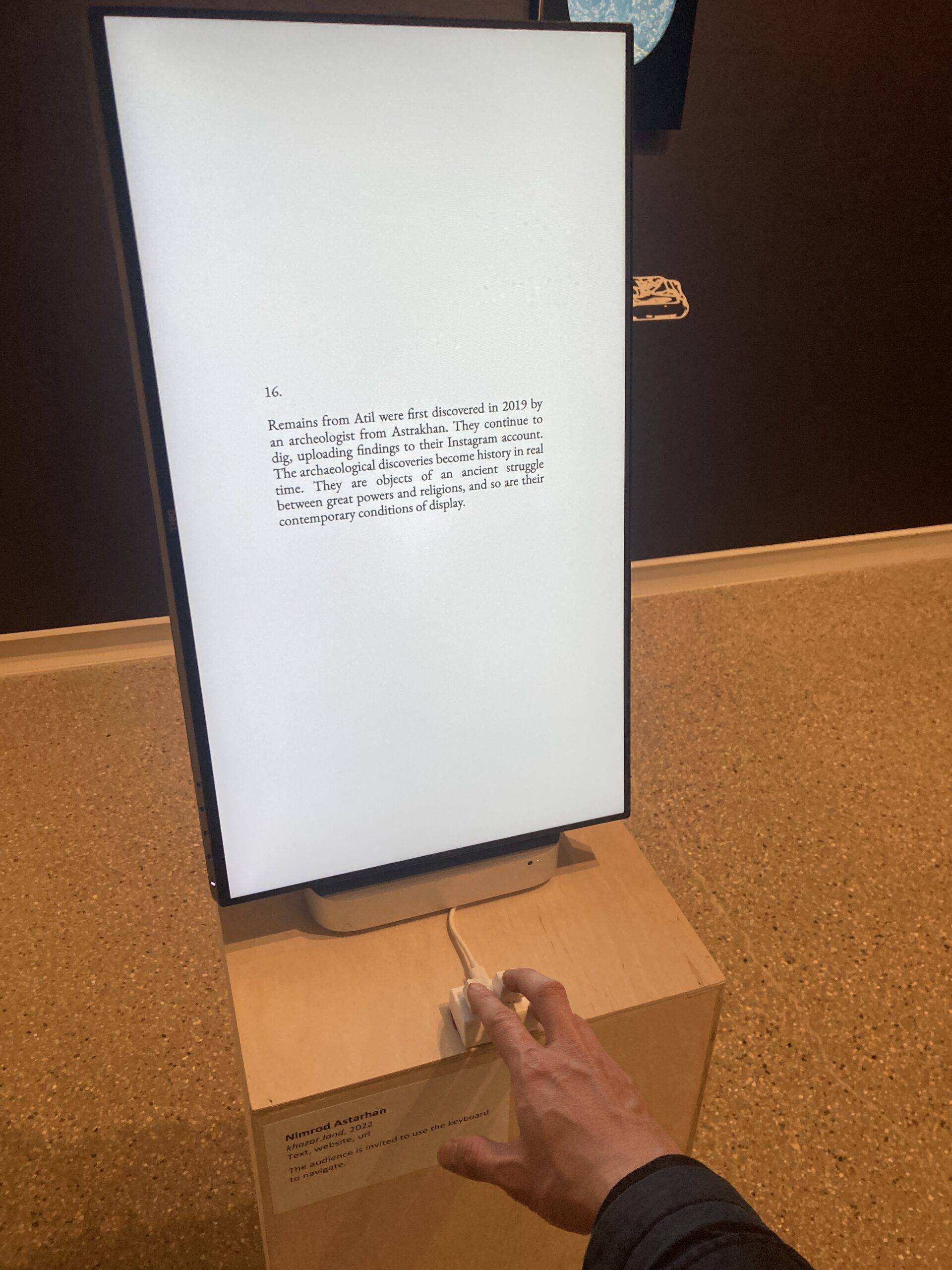

Q: In regard to “Khazar.Land,” the artwork you exhibited, how do you see net art as a medium for exploring identities? And why is net art a useful or precise tool to achieve that?

A: I see net art as working in public space. As such it has a great potential for mobility and access. The medium’s ephemerality and deterritorialization entail alienation and detachment from a specific community. The experience of net art is often intimate and unaccompanied. These are support for the diasporist approach I am taking. In the work itself, I balance citing sources to establish trust, while retaining poetics and speculation.

Q: Your graduate show features game consoles, net-art interaction, and cyanotypes. What is the rationale behind bringing all these drastically different media in the same area?

A: My practice is post-conceptual, but I was trained in the modern tradition. As such, I see these mediums as carriers of inherent meanings. The Khazars believed in the eternal blue sky. Exposing the cyanotypes under the sun in Millenium park is a way of embedding the Chicago sky in a pictorial method of depicting the speculative archeology objects I have created. Similarly, the game consoles are reminiscent of choice and participation, which are ways in which the history of the Khazars is portrayed throughout the project, with every historian and religion writing their own version of it. Each medium has its way of being enmeshed with work on a specific part of the project.

Interview with Mac Pierce

Q: While technology provides convenience, it also takes away things like privacy from people. How do you feel about technologies acting as a double-edged sword? Do you have any opinion on the recent surge of AI-art? And do you use the potential of using it in your work?

A: The dual nature of technology is an integral part of its use. ‘Technologies’ are just tools, and like any tool they can be used to create and destroy. Fire is created for warming your home, but it can just as easily be used to burn down your neighbor’s home. It’s something I always try to keep in mind when working and talking about tech, as so much of the rhetoric about emerging technologies points towards techno-utopianism, but behind all tools are the people that use them. In the case of surveillance technologies, those tools are controlled by law enforcement and corporate interests, and I think there are plenty of reasons to want to push back against both.

In regard to AI-art, it’s an art making tool like any other. Just one with a lot of hype and money behind it, both of which usually don’t lead to a lot of good art being made.

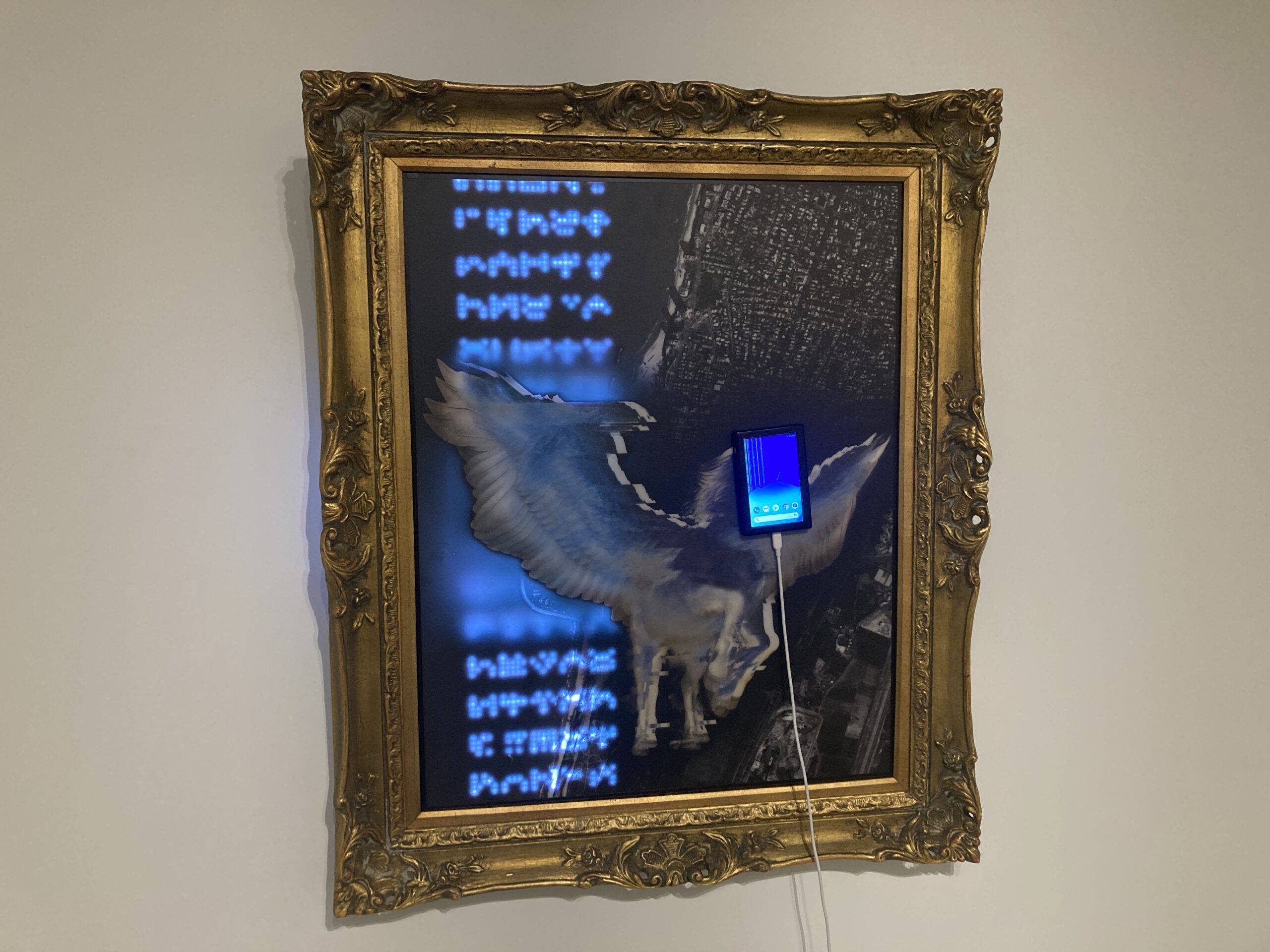

Q: Can you unpack a bit on the aesthetics and rationale behind your work “Portrait of a Digital Weapon – Pegasus”?

A: “Portrait of a Digital Weapon – Pegasus” is the third in a series of portraits of cyberweapons deployed by nation-states. In this iteration, the portrait is of the Pegasus spyware, a particularly nasty tool developed by the Israeli company NSO Group and licensed to governments around the world. When used, pegasus could automatically take over a cell phone and turn it into a pocket spy, allowing the government to use it to record audio, look at messages, and grab the GPS data from the device. The portrait depicts a number of elements in its use, including the full scrolling code of the virus, a faux phone that appears to be broken, and a USB cable that powers the piece.

I hung the portrait within a traditional golden frame to place it within the context of military portraiture, whereby battle scenes and weapons are depicted for the historic record. It’s important to categorize these sorts of viruses for what they are, cyberweapons being used to carry out violence against those they’re employed against, such as journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the case of Pegasus, so including them within that canon frames them as such.

Q: Your works draw heavy references on surveillance, which is an important awareness especially for consumers. How do you extend the accessibility of your works so more viewers are aware of it?

A: As an object maker, it’s a question I am constantly considering. It’s all well and good to make a sculpture and place it in a show, but ultimately those spaces have their own restrictions on reach and the breadth of thought they inspire. To push those bounds, I’ve made it a practice to heavily document their construction and then write about the projects in a way that can live online. All of my recent projects I’ve released under a Creative Commons license so that others can learn from what I did and draw inspiration from it. One recent semi-speculative project, “the Camera-Shy Hoodie,” I published a full build guide so anyone that wanted could make their own. As a result, that project went viral, with multiple news outlets covering the project and millions more people seeing and thinking about the topic of surveillance in their lives.

Q: Any remarkable moment or collaboration at SAIC that shapes or inspires your practice?

A: My biggest inspiration at the school has always been the other students, in particular the other graduate students. The breadth of skill and the passion for their work has driven me to make my work better, and I’m constantly floored by how impressive their practices and production is. I was also once told by an advisor that I should be ready in case I’m arrested because of my art, so I think I’m doing something right.

Interview with Eugene Tang

Q: Your project starts up as a single-channel video. What is your rationale behind displaying your “interviews” as a multiple-channel installation?

A: This project starts as a two-channel work, where photograph and video exist side by side. I showed the conversation between me and the model with the shot at the moment, so the video is based on the ephemeral nature of making those photographs. The multiple-channel version is not only just playing with the desire of audiences by not showing photos, but also gives me more parameters of showing the photographing process including preparation, direction, loosening them up, rather than just those ephemeral moments which stick to the concept of photography. Plus, when I added the choreography in the presentation, I knew the work spoke for itself and no longer needed to rely on the artist’s statement.

Q: As a photographer, how do you play with the difference between static and moving images?

A: I think there’s a notion that photography creates enchantment in an image. Deliberately, my project “A fly on the wall, a deer in the headlights” becomes a moving image showing disenchantment. It doesn’t mean it’s less interesting, but sometimes it is surprisingly more interesting based on how frequently we see nude portraits throughout art history but rarely talks about how it has been produced.

Q: Is photography/video a compelling idiom for you to explore LGBTQ+ themes? Do you see yourself expanding your techniques into other media in the future?

A: Actually, no. I combined my former queer study into photography very late, probably only since 2020. And photography actually gives me a chance to blur the binary line between LGBTQ+ and straight. I started to stop using “LGBT” to describe my work because I realized that sexuality isn’t simply a categorized genre. Especially when I am sharing someone’s vulnerability and intimacy, I see everyone as a unique human being more than their identity and sexuality.

I think as long as the material I use can create conversation, I’d give it a try. I am not very geeky about that, but I also don’t like to use material without basic knowledge of it. Each discipline has its materiality and history to be known and that’s always the most crucial part of being used. I am now thinking about video choreography.

Q: Any remarkable moment or collaboration at SAIC that shapes or inspires your practice?

A: There are two reasons why I start to draw attention to provocative topics. Firstly, I studied anthropology when I was in Taiwan. All we do is to explore the unknown in our daily lives. Secondly, the SAIC photo department was known for its subversive perspective while Barbara DeGenevieve was leading the department. I got a scholarship commemorating Barbara which entitles me to do something challenging to myself.

To view these artists’ works, check out https://sites.saic.edu/gradshow2023/filters/grad/.