Japanese print works have long served as a medium to capture common people’s daily lives, and ukiyo-e (“picture of the floating world”) print is a staple and prominent genre of such. Despite the two-century-long tradition since the seventeenth century, early twentieth-century Japanese artists urged to rejuvenate printing approaches. To record modern urban life better, they made significant changes in terms of printing techniques, subjects, and compositions.

The exhibition “Recollections of Tokyo: 1923–1945” (July 2, 2022 – September 25, 2022) at the Art Institute of Chicago showcased Japanese printmakers’ contemporaneous attempts. The works also interrogated historical complications experienced by Japanese artists in that period. To exemplify this idea, this article discusses four relevant prints of night scenes to navigate us through the turmoil they encountered.

Deviating from the traditional style, Japanese prints from 1923–1945 emphasized bolder shapes, thicker lines, and a more limited color palette. Instead of inheriting subtle color gradients and fine details from tradition, the printmakers experimented with blobs of colors. Sumio Kawakami’s “Yoru no Ginza” (“Ginza at Night”), part of the “One Hundred Views of New Tokyo” series, is a woodcut print finished in 1929 and printed in 1945 as recut blocks. Kawakami limited his colors to magenta, cyan, brown, black, pale green, and navy blue. This choice loosely resembled the CMYK color model—as one would relate to the influence of the commercial printing process. Compilations of simple shapes, instead of outlines, formed the figures in the print. The shadows and highlights, appearing bold and plain, replaced subtle color gradients in traditional prints. Though “Yoru no Ginza” shares an uncanny resemblance to Gustave Caillebotte’s “Paris Street; Rainy Day” (1877) at the Art Institute, Kawakami’s work cared less about details and perspective. The lack of fine details and depth seemingly pointed toward the quick pace of city life, echoing the Italian futurist aesthetics. The swiftness of urban lifestyle encouraged the bold use of shape to narrate speed, dynamism, and rapid industrialization through technologies. The no-frill design demanded and focused on practicality through undecorated geometric shapes, reminding viewers of the Bauhaus style.

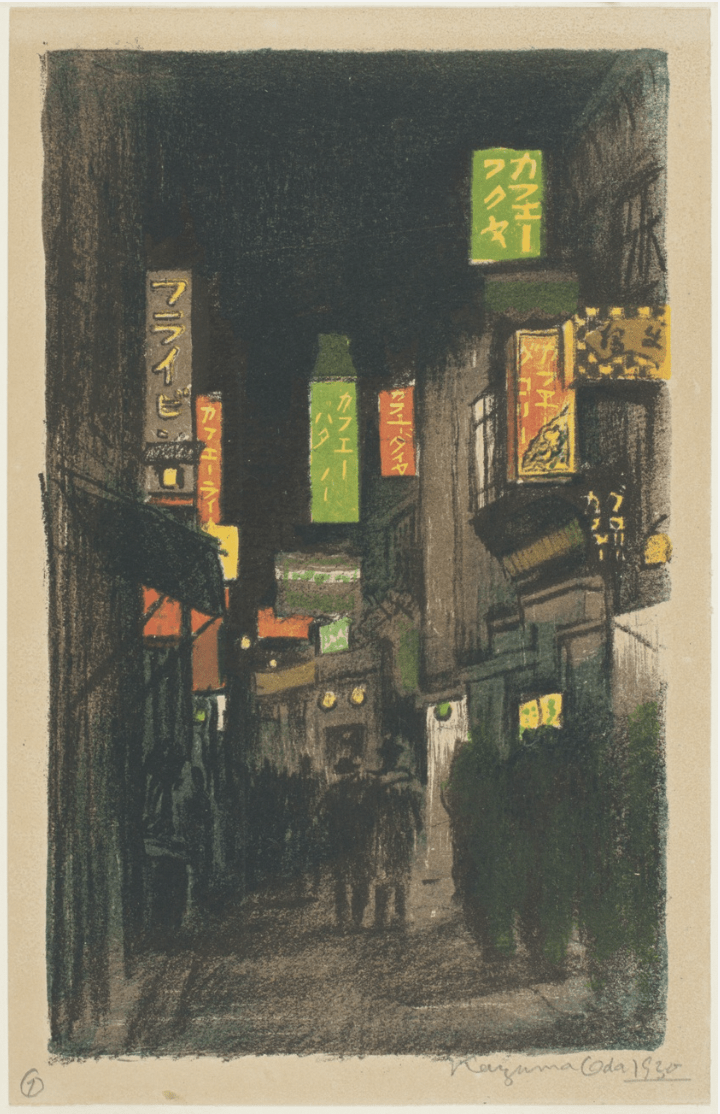

Besides “Yoru no Ginza,” several other works depicted night scenes in Tokyo. They provided a great hint at technological advancement. Japan had its first known gas light in Yokohama in 1872. The introduction of electricity and outdoor lighting not only lit up the spectacular nightlife, but it also enabled artists to envision night scenes as new sources of inspiration. Oda Kazuma’s “Shinjuku kafe gai” (“The Café District in Shinjuku”) (1930), from the series “Scenery of Shinjuku,” displayed a street scene of neon signs. Truthful to a camera lens or human eyes’ perception at night, the work highlighted the pop-up of neon signs in the darkness. In a low-lit situation, light-emitting objects become the only clear subject. The shadows were skillfully depicted through shades that resembled a fuzzy charcoal drawing.

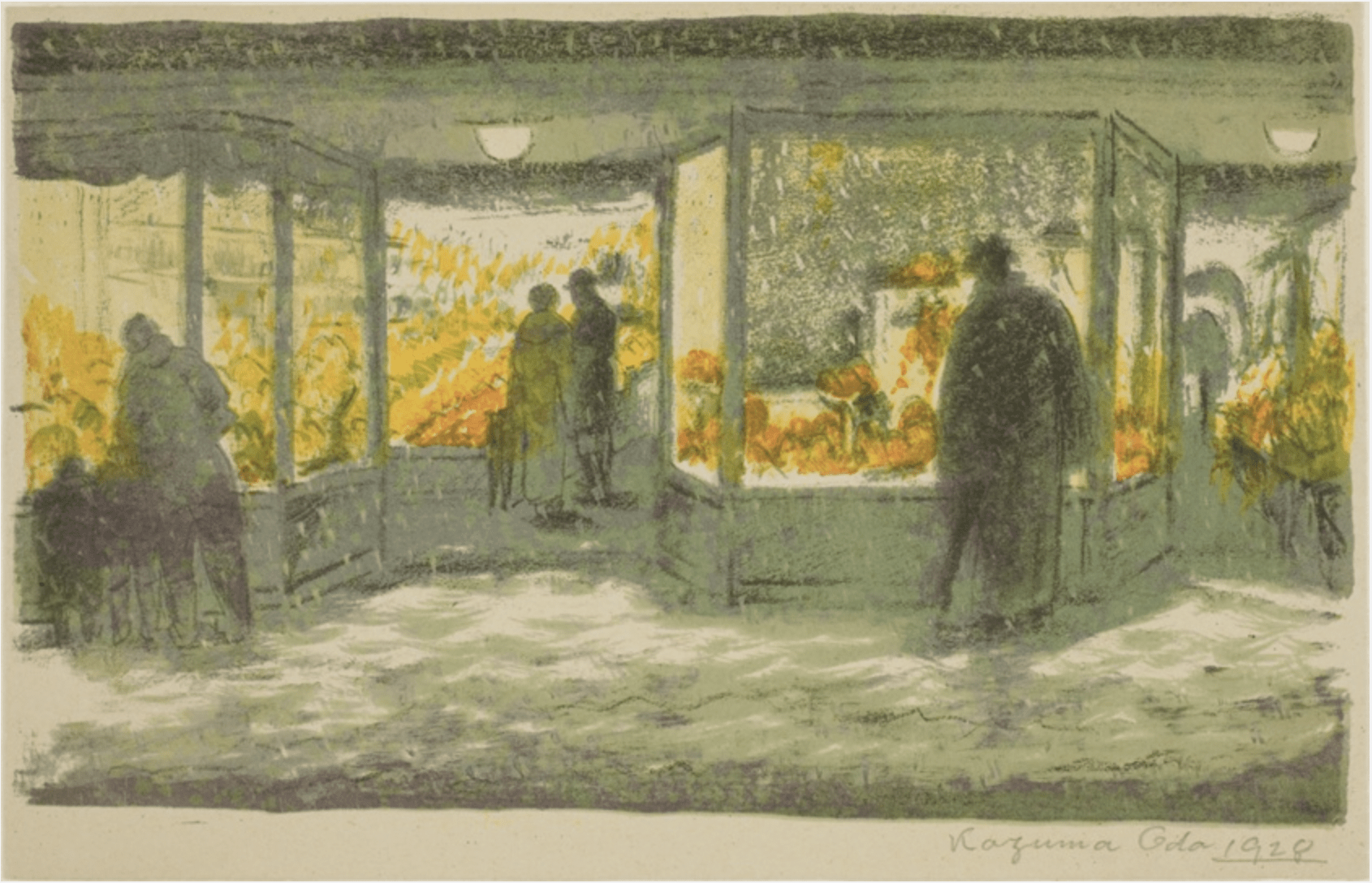

Besides the modernized version of Japanese woodblock prints, Oda Kazuma’s involvement in color lithographs, a Western printing technique using flat stone/metal surfaces, is worth mentioning. Kazuma’s “Ginza Senbikiya” (“Senbiki Shop in Ginza”), from the series “Pictures of Ginza, First Series” (1928), was an early example of lithograph in Japan. The pedestrians face away from viewers in the form of rückenfigurs (“figure from the back”). The lack of facial details contrasted highly with traditional prints that featured individual heroic characters, kabuki theatre actors, etc. To illustrate the dim light on the street, Kazuma used a very muted palette that utilized yellow, orange, and brown. He also employed a considerable amount of gray and black to represent shadows in the dark. Another interesting scene was that Kazuma did not depict any actual purchasing scene, but he portrayed the act of window shopping. The lack of buying activity seemed to contradict what one would expect. The glass window of the shop also created a sense of alienation from the pedestrians. This distance is a good twisting point where viewers start questioning if the artist celebrated modern urban life, or whether they were in doubt about accepting Westernization.

The uncertainty imported by modernization and Westernization created equivocal dynamics among the Japanese people. The Perry Expedition (1853–54) effectively, and forcibly, ended the 220-year isolation of Japan in 1854. Less than one hundred years of the forced opening, Japanese people encountered the dilemma of whether to embrace Westernization or retain the Japanese traditions: some expressed doubt, refusal, and unacceptance of Western culture (as strongly hinted in Natsume Sōseki’s novel “Wagahai wa Neko de Aru” [“I Am a Cat”] in 1905–06), some other attempted to catch up with Western standard and preference. Though the acceptance of Western culture became inevitable, this approach was further complicated by the involvement of the Japanese Empire in World War II. Japanese printmakers, besides continuing their fondness for representing daily lives, also examined their ambiguous and confusing psyche through introspection.

In Senpan Maekawa’s “Shinjnku no yo” (“Night of Shinjuku”) (1945) from the series “Scenes of Last Tokyo,” the rückenfigur in coat hints the artist’s introspection through the period of unrest and trauma from the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Though the protagonist appears in the center, the figure is facing a cluster of modern buildings, a lighthouse, factories, an electrical tower, and power lines. There is also a car driving away from the scene, leaving only the very rear part visible. The print is mainly black and white, with a dash of red highlighting the fence and tower; also a trace of blue on the buildings and the car. Instead of mingling on a crowded street, this lone man confronts what he is facing, a city developed under a heavy foreign influence. Though the work shows the quick recovery from the devastating earthquake, the new cityscape also loses the reference to traditional Japanese architecture. The interpretation of this print remains ambivalent—did Maekawa simply outline how a modern metropolitan would look like, or did he question the direction and take that the Japanese had to decide moving forward?

The prints in this exhibition belonged to the Sōsaku-hanga (“creative prints”) movement. This school of thought opened up new ways for Japanese printmakers to become individualistic for the art’s sake through “self-drawn” (jiga), “self-carved” (jikoku) and “self-printed” (jizuri)—contrary to the traditional printing practice as a collective. The overloading of Western influence and unsettling wartime, however, also facilitated “self-doubt” and “self-inquisition.” Prints assuredly affirmed as practical snapshots of urban lives. They also documented the early twentieth-century Japanese artists’ effort and experience of way-finding under the inexorable influence of modernization and Westernization.