The allure of old technology is something that will always be there. The inherent nostalgia of film grain and the ability to imbue ordinary scenes from daily life with the hazy feeling of dreams long past has enough power to make old point-and-shoot film cameras and miniDV cameras worth hundreds of dollars. As someone who is digitizing old home movies, what I’ve always found interesting is what makes the cut to be filmed. Compared to today, when you can film an endless amount of whatever you want, having to make choices on how to best use your 30 minutes or so of tape is a real decision.

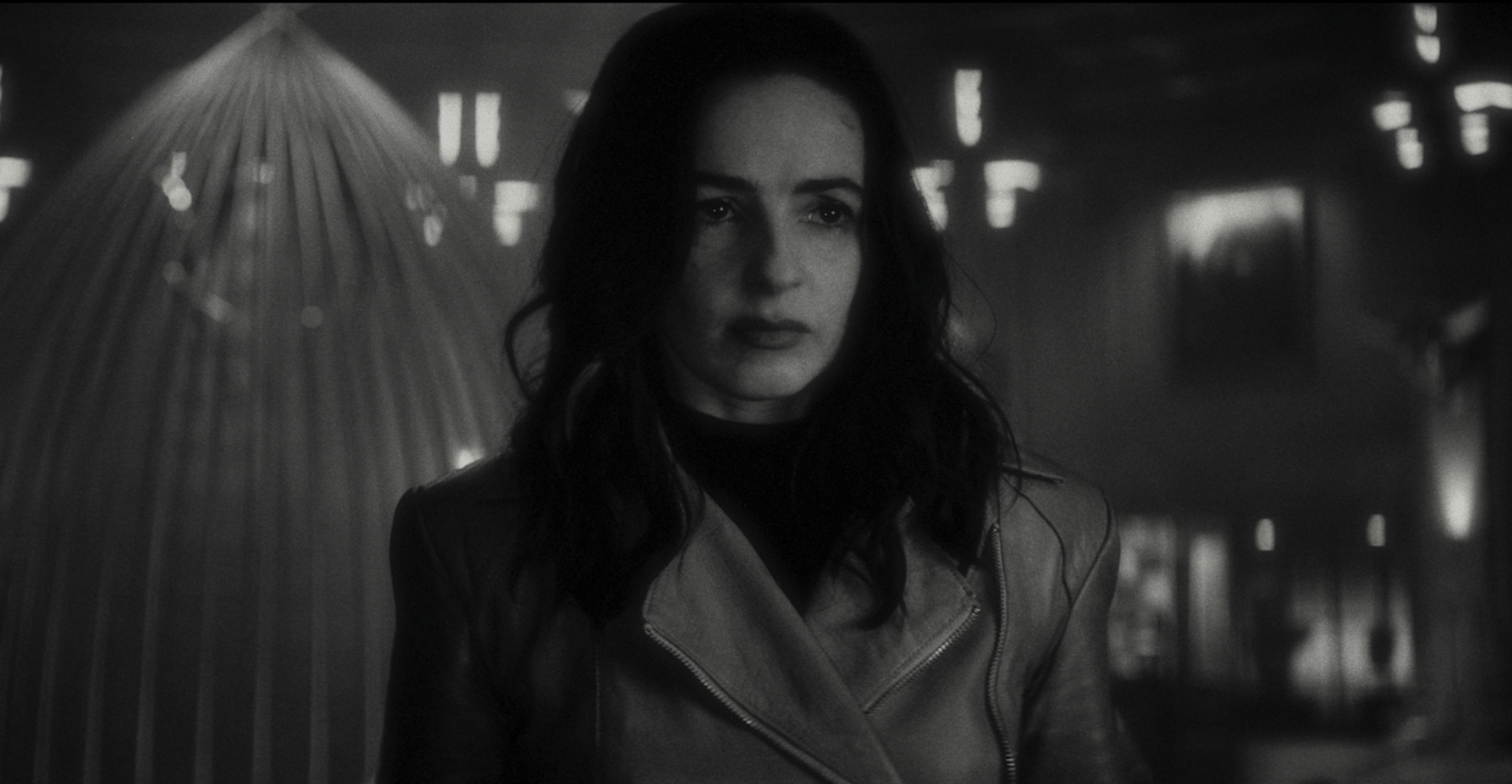

Charlotte Wells’s “Aftersun” takes this nostalgia and inverts it. The film focuses on looking at the past with a knowledge you could have never had as a child and the horror that can bring. Sophie (Frankie Corio) is an 11-year-old girl on vacation in Turkey with her father Calum (played brilliantly by Paul Mescal). The film consists of vignettes from their vacation, along with scenes shot on a miniDV camera. As the film progresses, you see an emotional weight bearing down on Calum get heavier and heavier. He clearly loves Sophie very much, but being the father of an 11-year-old girl when you’re barely 30 yourself is enough to crush anyone’s dreams. His life has not turned out the way he’s wanted it to. These scenes are intercut with a flash forward of an adult Sophie dancing at a nightclub, searching through the crowd for a man who looks just like Calum.

What we get to see in “Aftersun” is just as important as what we don’t get to see. There are many scenes where we can only see through reflection, or glass, or it’s so abstracted that we don’t know what we’re looking at. While I was watching the film, I kept waiting for something to snap. A creeping tension lurks beneath the surface, and I kept waiting for the other shoe to drop. The sense of a bad ending, or a devastating twist, is inevitable. And the film makes plenty of room for moments where something bad could indeed take place, but it never really does. Nobody ever snaps, nobody hurts Sophie, and she doesn’t even really see anything that could be scarring. We will never know why this footage is so important.

“Aftersun” reminded me the most of Michael Haneke’s “The Seventh Continent.” Haneke and Wells both shoot their subjects and environments very similarly. Both focus on their characters’ possessions, minute details of the environment, and use long takes not for grand gestures but to allow their audience to sink into this tense situation. (There is a shot of a television in “Aftersun” that I have to think is a direct homage to Haneke’s “Funny Games.”) But where Wells and Haneke differ is that there is no violence in this film, direct or indirect. You never get to see what happens, or why anyone really feels the way they do. Mescal, who portrays Calum with the tact and weight of someone years beyond him, only breaks down once, with his back turned to the camera. Just like Sophie, there are things we will never have access to.

“Aftersun” is one of the sharpest debuts I’ve seen in a long time. Wells moves with the precision of a veteran here, and Paul Mescal gives an absolutely incredible performance for someone who could have easily coasted off of “Normal People” into a cushy life of playing an Irish heartthrob. It is such a breath of fresh air to see a film about family trauma that approaches the topic with such a cold, yet confrontational lens. I left the theater feeling absolutely destroyed. “Aftersun” is one of the best films of the year, and one that I really hope gets some love come Oscar season.