“Auteur Theory” is a column in which Aidan Bryant dives deep into the work of some of the most original filmmakers of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Why are movies afraid to make you uncomfortable?

The idea of an uncomfortable movie is one that is at odds with modern cinema. Today, we often see movies as mere “content” — an idea that became more prevalent as streaming platforms became one of the predominant methods of releasing movies. Even films by popular directors like Martin Scorsese, Jane Campion, and Alfonso Cuarón have gone pretty much streaming-exclusive, save for a limited cinematic release to meet Oscar requirements. While I don’t think their films function as “content,” they are certainly treated as such by the companies that release them. There are films that are explicitly made to be content, streaming or not. What I mean is that the movie is not meant to challenge you. It is not meant to provoke any serious feelings or thoughts. It may reinforce your own thoughts, perhaps, but it will never lead you outside of the film to anything else. The purpose of the film is to consume it, and nothing else. This is not a new phenomenon, but the arrival of streaming services mean that we can now easily see the Hollywood machine for what it is.

One thing I would like to make clear is that my criticism of these films is not rooted in the idea of “good movies.” A common retort to lots of film criticism now is, “Let people enjoy things!” or, “Not everything has to be a boring art movie.” I think one of the most damaging things to modern cinematic discourse is the idea that people who write about, or make, or study film for a living all sit around watching art films all day, and consequently, that those films are boring. There are plenty of fantastic films that are very accessible and popular which also take risks, make you feel things; make you actually think. The work of directors like John Carpenter, early James Cameron, and Nora Ephron are all perfect examples of this, and they are beloved figures in the film community; massive inspirations that are consistently ranked as masters of their craft.

To the notion that “art films” are boring, I’ll quote Scorsese in a letter written to the New Yorker regarding their description of Fellini as inaccessible to most audiences. “It reminds me of a beer commercial that ran a while back. The commercial opened with a black and white parody of a foreign film — obviously a combination of Fellini and Bergman. Two young men are watching it, puzzled, in a video store, while a female companion seems more interested. The solution is to ignore the foreign film and rent an action-adventure tape, filled with explosions, much to the chagrin of the woman. It seems the commercial equates “negative” associations between women and foreign films: weakness, complexity, tedium. I like action-adventure films too. I also like movies that tell a story, but is the American way the only way of telling stories?”

Coloring these films as boring is inherently limiting the kinds of films people are willing to watch. I will admit that part of the reason these movies are viewed as boring is because of insufferable film students who hate anyone who watches an action film, but that breed is dying out. My experience is that people who are truly passionate about film love all sorts of movies, from Haneke and Kiarostami to big blockbuster filmmakers like Tony Scott. They love movies made by people who care about the process of filmmaking, no matter the scale, style, or era. These films I will be discussing, blockbuster or not, lack that care and heart. They are so processed, so hands-off and detached, they lose any human element to them.

I’ll start with “In The Heights,” because it is the one most rooted in a rich cinematic tradition — both in the movie musical, and more importantly in New York cinema. The history of New York cinema has produced some of the greatest films ever made, both by big-budget Hollywood studios and by low-budget indie filmmakers. It is a tradition that feeds off of itself, all the way from Lumet to modern practitioners like The Safdie Brothers and Emma Seligman. What makes all of these movies so great is that they feel real. They’re made by, and feature people and stories that accurately represent the place they’re depicting, and most importantly, represent that place with all of its idiosyncrasies, flaws, and ugliness. “In The Heights” feels like a movie made by an 8th grader who went on a school field trip to NYC. It’s made of plastic. Sure, the audience is sold the idea that it is an authentic depiction of New York City, but that depiction is so hollow and lacking any of the actual issues facing the city. The cultural signifiers of Washington Heights feel as forced as pro-wrestling catchphrases thrown out at the audience; meant for cheap, easy reactions. Gentrification is represented by dry-cleaners charging more money and using a touchscreen checkout system, not by hulking corporations snatching up buildings to convert into apartments for a massive influx of white-collar workers into a neighborhood that previously housed minorities and the disenfranchised.

The film doesn’t want to attack the messy parts of NYC because it is afraid to challenge the audience Lin-Manuel Miranda has cultivated — old, white liberals. “In The Heights” acknowledges New York City’s biggest problems at a base level, but solves them through “hard work” and “representation.” The reason why a dry-cleaner serves as the symbol for gentrification is because the real answer would alienate their core audience. It reinforces an ideology that was drilled into its audience’s heads since grade school, at the cost of infantilizing some of the biggest issues facing us today.

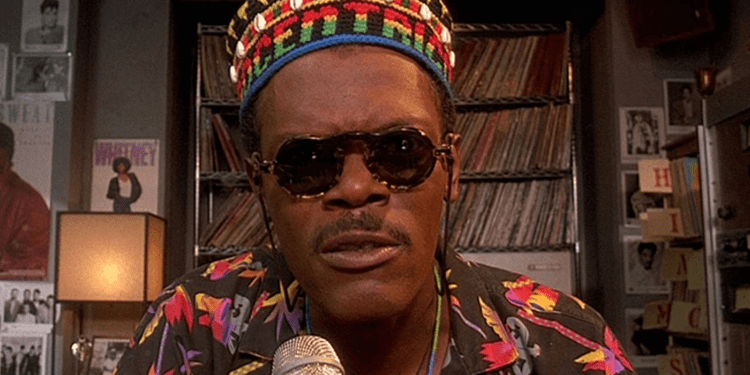

To compare this film to Spike Lee’s “Do The Right Thing” is almost too easy, but the comparison is perfectly apparent. First off, both films prominently feature heat waves, a staple of NYC cinema (this is also a key point in Lumet’s “12 Angry Men,” arguably the first quintessential NYC film). Both also claim to represent a neighborhood truthfully, with “Do The Right Thing” being set in Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn. Where the films diverge is the fact that Lee is not afraid to present you with an actual idea; an opinion. His perspective is his own, mediated through personal experience, culture, and historical context. The film is steeped in the 1980s. Constant references to athletes, musicians, and prominent news stories — I would argue this film doesn’t exist without the Howard Beach case — make it feel real. But the real difference between the two films is their relationship between the audience and the film itself.

“In The Heights” does not respect its audience. It doesn’t care about them at all. You are spoonfed the exact opinion you’re supposed to have until the film is over. “Do The Right Thing” does the opposite. It forces you to actually think. You are presented with characters that are complex. Mookie, our main character, is not a shining example of morality. He is a bad father, he slacks off on work, and seems to be motivated purely by making money. Characters are constantly arguing, insulting each other. There is a constant tension simmering throughout the film, but there are no major sweeping moments, just small ones. Lee does not manipulate his audience, he guides them. To be stereotypical, he is painting a picture. And as that tension builds and builds and builds, when it finally explodes, you are forced to witness it. You cannot walk away from this movie without having an opinion. You have to actually fucking think about the film itself, and your relationship to it. You are implicated within it.

I may be biased. Not to be overdramatic, but “Do The Right Thing” really changed my life. I had never seen anything like it before my dad showed it to me as a teenager. It gave me a perspective I didn’t have, growing up in the suburbs. It made me realize that there are things outside of myself. A great movie can do that for you. And this is not some highbrow, pretentious movie. There is an entire scene in this movie dedicated to discussing the difference in quality between Miller High Life and Miller Lite — two beers that the stereotypical pretentious film critic would turn up their noses at.

Adjusted for inflation, “Do The Right Thing” would have made over 85 million dollars in 2022. That’s not a king’s ransom, but it isn’t insignificant. People know what this movie is. And while it does have a great cinematic influence (Mathieu Kassovitz’s “La Haine,” and Justin Chon’s “Gook” are both clearly influenced by it, and are both excellent films), I don’t see as many movies that make me feel like it did the first time I watched it. Maybe I’m just old and bitter, but I’m not that bitter. When I go see a movie I want to love it, because I truly love movies, probably more than anything else. I’ve loved them since I was a kid. That love will never go away, but it’s getting sadder and sadder.

Not every movie has to be “Do The Right Thing,” but we aren’t even getting fun movies anymore. We’re fed overproduced, focus-tested garbage that studio executives cut and re-shoot 50% of the time anyway. Horror movies seem to be allowed to cook up something interesting, with Ari Aster and Jordan Peele leading the way, but who knows how long that’s gonna last. Profits are being maximized while directors are being flushed down the drain. Even rom-coms have no magic anymore. Compare “Sleepless in Seattle” or even “13 Going On 30” to a movie like “Marry Me,” which is so empty it feels like it could have been AI-generated. Where’s out new Nora Ephron?

I’m not asking for high art, I just want to feel like I’m seeing something the people who made it got to actually make. I want to see a perspective that is actually someone’s, with all of its flaws, and biases, and personal tastes. I want to see Tony Scott hand-cranking the camera during a big budget action movie, or Robert Altman zooming all over the place. I want to see exciting new directors like Emma Seligman, Joe Talbot, and Lee Isaac Chung not get chewed up and spit out by some big corporate machine like some of their fellow auteurs have — aka Chloé Zhao directing Marvel’s “Eternals,” to name a few. I just want to feel something that I don’t already know. I want to get in someone else’s head for around two hours and see what it’s like there. I don’t know how often I’ll get my wish anymore, but I’ll keep looking for it.