The work of Soledad Fátima Muñoz (MFA FIBER 2019) keeps memory alive. Her artistic practice centers on her Chilean heritage, combining sight and sound to commemorate the victims and survivors of Chile’s authoritarian past. She currently lives and works in Toronto, Canada.

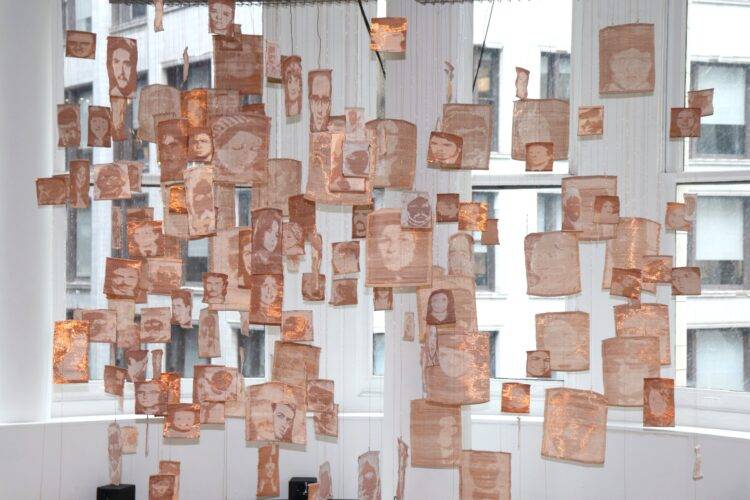

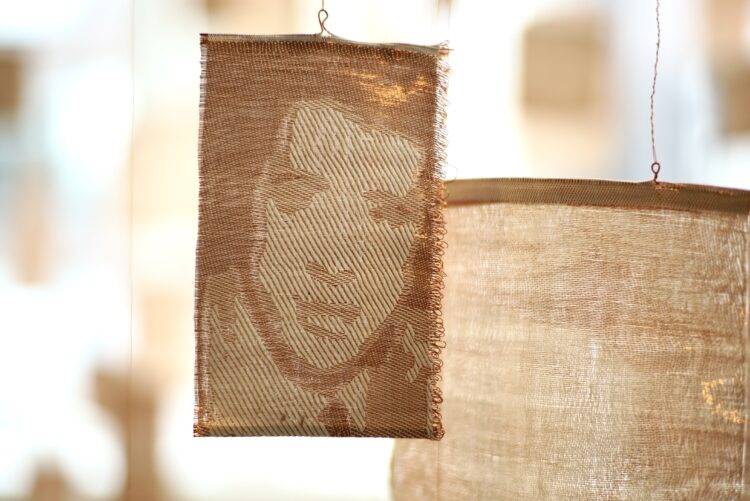

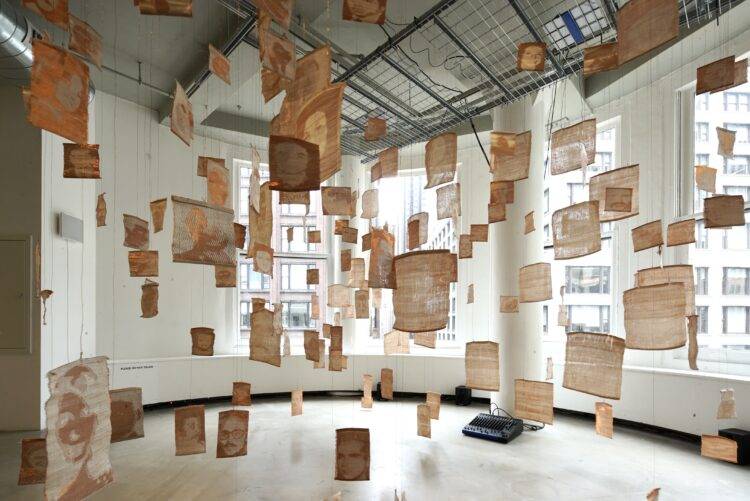

Recently, Muñoz’s work “Detenidxs Desaparecidxs/Disappeared Detainees” was featured at the Uri-Eichen gallery in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago. The work, normally a three-dimensional audio-visual installation but reconfigured as a window-display, features copper-wire portraits of disappeared Chileans who vanished during the aggressive dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1991). It also highlights the regime’s ties to the city of Chicago — it was at the University of Chicago that the Chilean “Chicago Boys” economists studied, and brought back with them the neoliberal policies that would contribute to disastrous economic inequality. In unifying these strands, Muñoz constructs a poignant site-specific work of presence and absence, calling attention to victims and perpetrators in a struggle that continues to this day.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Just to talk a little bit about your background — I know you were born in Canada, but your family’s from Chile, but then you came to Chicago to study [at SAIC].

I was born in my family’s exile in Canada. So I think that is very specific, and also just comes back into my life all the time. That being said, I did spend 15 years in Chile, from when I was five until I was 21. So I live between these two worlds, and I feel like that’s the case with a lot of the people who were and are still in exile.

So your family returned to the country after the end of the Pinochet regime?

Yes, in 1991. So after the election of [President Patricio] Alywin, who now we understand was not a return to democracy. [Editor’s Note: the 1989 election of Patricio Alywin as president of Chile marked the transition back to democracy after the Pinochet regime, although it did not truly conclude the dictatorial period.] There was still a lot of the dictatorship that we saw come to light in the October Revolution of 2019. It wasn’t as smooth as the history books tell.

So during this time, is this when you started to become interested in art? Or had you been interested previously?

I feel like I was always an artist. I feel like a lot of artists feel that way as well, where you don’t really fit either because I was a kid of exile. Or just because I thought very differently from everyone else that I was in school with. So I always say that skateboarding was my first introduction to art, because the same things that I try to do with art now is what I found refuge [in] when I was a teenager skateboarding, like a community.

Actually, because I broke my knee and I couldn’t skateboard anymore, the natural transition was to be a videographer. And that’s how I got into film, and that’s how the first thing I did was to go to film school. And then after that, things fell in place. Then I went to textile art school, but everything stems from that.

That’s an incredible turn of events. Is there a strong skateboarding culture in Chile?

It was huge — it still is. I come from a small city called Rancagua. And there weren’t any skate parks or anything when I was growing up there, so we just had spots [to skate]. But now, it’s grown even more, and it’s just nice to see. I feel like after the feminist uprising that there was, I feel like a lot more women, femme, or non-binary people are also skateboarding, which was not the case when I was there at all — I was the only one, me and another person and other women. We were the only ones skateboarding at that time.

And so in Canada, did you begin to study art and textile work?

So we moved [from Chile] because my mom has MS [multiple sclerosis], and it was literally because of the Chicago Boys. In Chile, if you don’t have insurance, or if you’re not able to pay for your illness, you would have died. And so thankfully, we were Canadians, and we were able to move back [to Canada from Chile]. It wasn’t really pursuing any art or anything; once we moved back, I was in Vancouver and I went to Emily Carr [University of Arts and Design]. And that’s when I realized that actually, I wanted to make art.

I didn’t find myself at all in that school [though], and so I went to textile art school [at SAIC], and that’s when the whole thing clicked and then I started really working a lot through sound and textiles.

So with “Detenidxs Desaparecidxs/Disappeared Detainees,” what motivated the decision to make it a gender encompassing term?

Yeah, well, because I guess the “x” represents either an “-a” or an “-o” [the common feminine or masculine suffix in Spanish]. In South America, we actually use the “-e” as a term more than the “-x”. And it is just because there isn’t just male[s who] disappeared, even though there are a great majority. There’s also women, so I just wanted to make a gender neutral title, because that’s just the fact — that it was both women and men that were detained and disappeared.

I was really curious how you got all the photos of the disappeared. What was the process of finding those?

So [“Detenidxs Desaparecidxs”] was actually my grad [thesis] from SAIC. The first installation of that piece was for my master’s thesis, and I was really fixed on having it in the corner of the Sullivan Gallery, because that corner is exactly the point zero of Chicago. It was really important for me to put the disappeared in the middle of Chicago, because of the relationship of the University of Chicago and the Chicago Boys to the coup. Those photos are all of public access.

So how did this current installation come to be at Uri-Eichen? Did the gallery reach out to you?

Well, that’s actually a really important question, because the person behind that show and the person that also asked me to get in contact with you, is very important for my practice. Her name is Ruth Needleman. [Editor’s note: Needleman serves on Uri-Eichen’s gallery board.]

She used to be a teacher at SAIC, but she also used to be a labor studies teacher [at Indiana University] before that, and she’s just done so much in her career. And now, she’s specifically focusing on the AFL-CIO [American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations] relationship to the coup in Chile, because she was in Chile in 1972. And she wrote for a resistance paper from that time, so we have been curating five months of programming together for the 50th anniversary of the coup, which is in 2023 … with all kinds of events to appeal to the memory.

Have you figured out the plans for these events or workshops yet?

So I did the show [“Detenidxs Desaparecidxs”]. And then I showed “La Parte De Atrás De La Arpillera,” which is a documentary-audio-visual piece that I did about the arpilleristas, who were the women who embroidered what was happening during the dictatorship. Then I sent it out to Europe and Canada, to tell what was happening during the dictatorship but also make some [kind of] living out of it. That was showing at the Nightingale [Cinema] in Chicago, and then I did a workshop with one of the arpilleristas. It was just so much fun, just trying to keep history alive. And boy do we need it, because yesterday the elections in Chile took place and a fascist is once again in the race. [Editor’s Note: the Nov. 21 general election in Chile saw the far-right politician José Antonio Kast succeed over his opponent Gabriel Boric. Kast’s platform includes denying climate change, opposing abortion and same-sex marriage, and support for the Pinochet regime.]

But [Kast] won and now we’re going to a second round and he’s literally a Pinochet supporter. And he’s the son of a Nazi, like a literal Nazi. Like, it’s just, wow. [Editor’s Note: Boric ultimately beat out Kast during the second round of voting and secured the presidency]

It’s incredible how circular history can be.

It’s wild. It’s so exhausting. People are like, “Why do you keep weaving the disappeared?” And it’s like, “Oh, I wonder why.”

It’s more relevant than ever, in a sense. Your work is really hitting that point. And I think that’s what’s so cool about it — that you’ve you’ve situated it in Chicago, which is so integral to the genesis of the regime, and it ties into memory, and marries visual aspects, like the copper with sound, to more ephemeral topics like memory.

Yeah, and that piece, when I first showed it, it was a sound piece — I thought of it as a sound piece, because some of the portraits are woven in a single weave, and those ones are more of a uniform surface of copper, which picks up vibrations like piano [wires]. They amplify vibrations. So it was as much of a visual thing as it was a sonic element to it. And that’s a little bit lost at the Uri-Eichen version, because we couldn’t do it as an installation because of COVID, and so it was just a window exhibition.

I wanted to ask, because I was looking at a photo of an earlier version where it’s all free hanging, and there were strings. But then the more recent photo shows them as flat. And so I was curious — what’s lost or even perhaps gained in this change?

The embodiment is lost, and I think that was a big part of [“Detenidxs Desaparecidxs”]. But at the same time, for instance, the new series that I’m making, not all of them have sound. For example, one is in the middle of the desert. There’s this mine [in Chile] where they found bodies of the disappeared, but [the Pinochet regime] dynamited it, so there’s still bodies that might be there, but they couldn’t find it. It’s like unmarked graves in the middle of the desert. And for me to go and install a piece there, I wanted to reactivate the space and, at the same time, bring memory. Instead of being the small pieces [like with “Detenidxs”], they’re going to be six feet by three feet. So you can see it from above. But obviously, those aren’t going to have sound, because it’s in the middle of the desert.

It sounds like these upcoming projects are so site-specific.

Absolutely. And thankfully in Canada, we have Canada Arts Council grants. And so I am able to give these installations to the communities [in Chile].

And how did these most recent projects come about? Have these been ideas that you’ve been thinking about for a while?

Yeah, everything has been a path. You know, when you’re in your path, it’s just everything clicks. And to find your path, it’s really hard. But once you’re in it, things just kind of happen and fall into place. And so from “La Parte De Atrás De La Arpillera,” I met Hector, an ex-political prisoner, who started the first arpillera workshop in prison, and is now part of La Providencia, which is the memorial site I’m working with. And so he saw my work and was like, “Hey, can we have one?”

And how many of these installations do you have planned for next year?

So there’s the one for La Providencia that I already wove [“Caravana de la Muerte”], which is of the victims of the death caravan that started in September 1973 and went from the south of Chile, killing people up to the north. Then the mine, also in the north in the desert, is for 2023, which is the anniversary [of the Pinochet regime].

It sounds like you have more than enough to stay occupied for a while.

Yeah, absolutely.

More about Soledad Muñoz can be found on her website and on Instagram. Her work “Caravana de la Muerte” is slated to be installed in Chile September 2022. Muñoz is also the co-founder of CURRENT: Feminist Electronic Art Symposium, a music and electronic art symposium featuring women and non-binary artists, and the founder of Genero, a audio project and label that promotes the work of women and non-binary artists.

Pablo Nukaya-Petralia is the art editor for F Newsmagazine. He is currently penning a spec script sequel to the “The Last Duel” (2021) titled “The Last Duel$.”