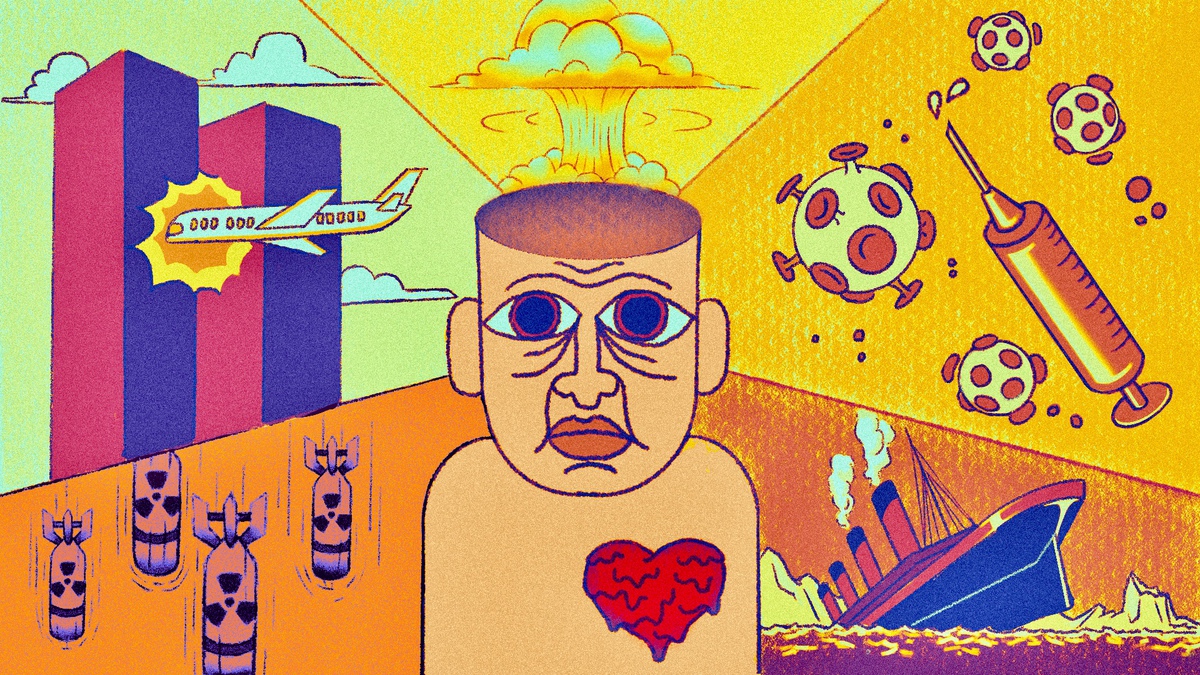

Illustration by Yajurvi Haritwal.

Maggie Nelson’s name, being one of the most influential contemporary American writers, is familiar to many. Most of us met her through her 2009 book “Bluets,” an exploration of heartbreak and color, or her bestseller, a queer memoir on motherhood entitled “The Argonauts,” published in 2015. Both texts are quintessential examples of her writing style — a versatile combination of autotheory and autobiography. Her vulnerable and assertive voice made her recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts in 2010 as well as the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2016. Last month, her 10th, and newest book titled “On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint” was published by Graywolf Press, surprising readers by gravitating towards a more traditional academic approach and tackling an immense subject: Freedom.

“Can you think of a more depleted, imprecise, or weaponized word?” Nelson’s introduction lets the reader know that this book is conscious of the limitations that surface when talking about abstraction and magnitude. Any attempt to commit to a single universal meaning would be impossible and unnecessary, so instead, she navigates the subject by acknowledging where one meaning starts and another ends. “In fact, it operated more like ‘God,’ in that, when we use it, we can never really be sure what, exactly, we’re talking about, or whether we’re talking about the same thing.” To partially solve the extension of it, Nelson focuses more on what would best be described as a Western account of Freedom, limiting her examples to mostly the American and European experience, and then sub-dividing the book into four central topics: art, sex, drugs, and climate change.

Part of the surprise when reading this book is the change from her usual style — also the case of her 2011 book “The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning” — into a more traditional and overly-organized one. Maybe this has to do with the fact that there is little to no autobiographical/narrative account on either of those, but this grants Nelson the possibility to appeal to a wider audience. This particular book is not accessible to anyone who grabs it. It is strongly committed to research, philosophical ideas, and pop-culture references. The names of Eve Sedgwick, Timothy Morton, Artaud, Walter Benjamin, Leo Bersani, Sartre, and Sontag, among many others, are constantly employed to support each analysis in a meticulous way.

In the first essay, “Art Song,” Nelson explores the complicated intersection between artist’s freedom and spectator’s demands and limitations, using the controversial painting “Open Casket,” a portrait by Dana Schutz of the Black, 14-year old Emmett Till who was lynched by two white men in 1955, as a supporting example. “Art is not a sacrosanct real, a ‘state of exception,’ whereby all one has to do is sprinkle some magic ‘it’s art’ dust on an expression or object and all ethical, political, or legal quandaries fly out the window.”

The same effort of reconciliation happens in her second essay, “The Ballad of Sexual Optimism,” a piece addressing, on the one hand, sexual abuse through the #MeToo movement, and on the other, the hypocritical treatment sexual urges have under the imposed illusion of “empowerment.” “What remains is a simulacrum of freedom: At one end, the ultimate symbols of marketable feminine sexuality protesting objectification; at the other, legions of ordinary joes opening emails urging, ‘Get bigger, last longer, become the beast she always wanted.’” Paradoxically, Nelson believes that the so-called “sexual freedom” people talk about these days runs the risk of becoming an unfreedom as it pressures everyone to have to indulge in a specific way of sexual liberation, otherwise shaming them.

In “Drug Fugue” Nelson sinks into the literature of addiction, which is mostly a male-dominated account on drug use that doesn’t end up in redemption, but heroism, creating a double standard sourced from the social binary of freedom. The way to understand the relationship between drugs and freedom has unending circularity: we are free because we can take part in a practice that allows us to forget our agency, but that creates a dependency on the factors that allow us to access that freedom i.e., addiction. Specifically, she dives into the problematic representation of drugs and their glamorization or effort to become overly transgressive in media. “Less fine I think, is to celebrate certain behaviors as ‘embodied practices of freedom,’ than to express disgust and censure when confronted with living examples at close range. At a minimum, such a reaction ought to remind us of the difficulty of difficult things, drugs not least among them.”

To wrap everything up, her last essay treats climate change and how it is becoming less of a Hyperobject and more of a tangible source of anxiety for herself, her son, and ultimately for us as well. This exposes how damaged our relationship to futurity is, and that we have somehow accepted the discourse that dictates the world is ending soon and learned to live in banal impermanence. “Morton says he wants ‘to awaken us from the dream that the world is about to end, because action on Earth (the real Earth) depends on it.’ For so long, I didn’t know what he meant. Now I do.” The consequences we are dealing with come from actions that took place decades ago, the same goes for what we do and how it will impact the world of future generations, people who like you and me, will be wondering why we thought it was too late to remedy. Even though this isn’t a call to action, it can feel like one, showing how climate change is impacting the way we choose to live either consciously or subconsciously through our impulses.

Despite her strong opinions, Nelson’s voice can’t be called prescriptive. It is more an exploration of subjects with no aim of convincing us that there is a right and wrong, but that analyzing is worthwhile and necessary in a time when we feel entitled to debate without warrants and based on brittle differends.