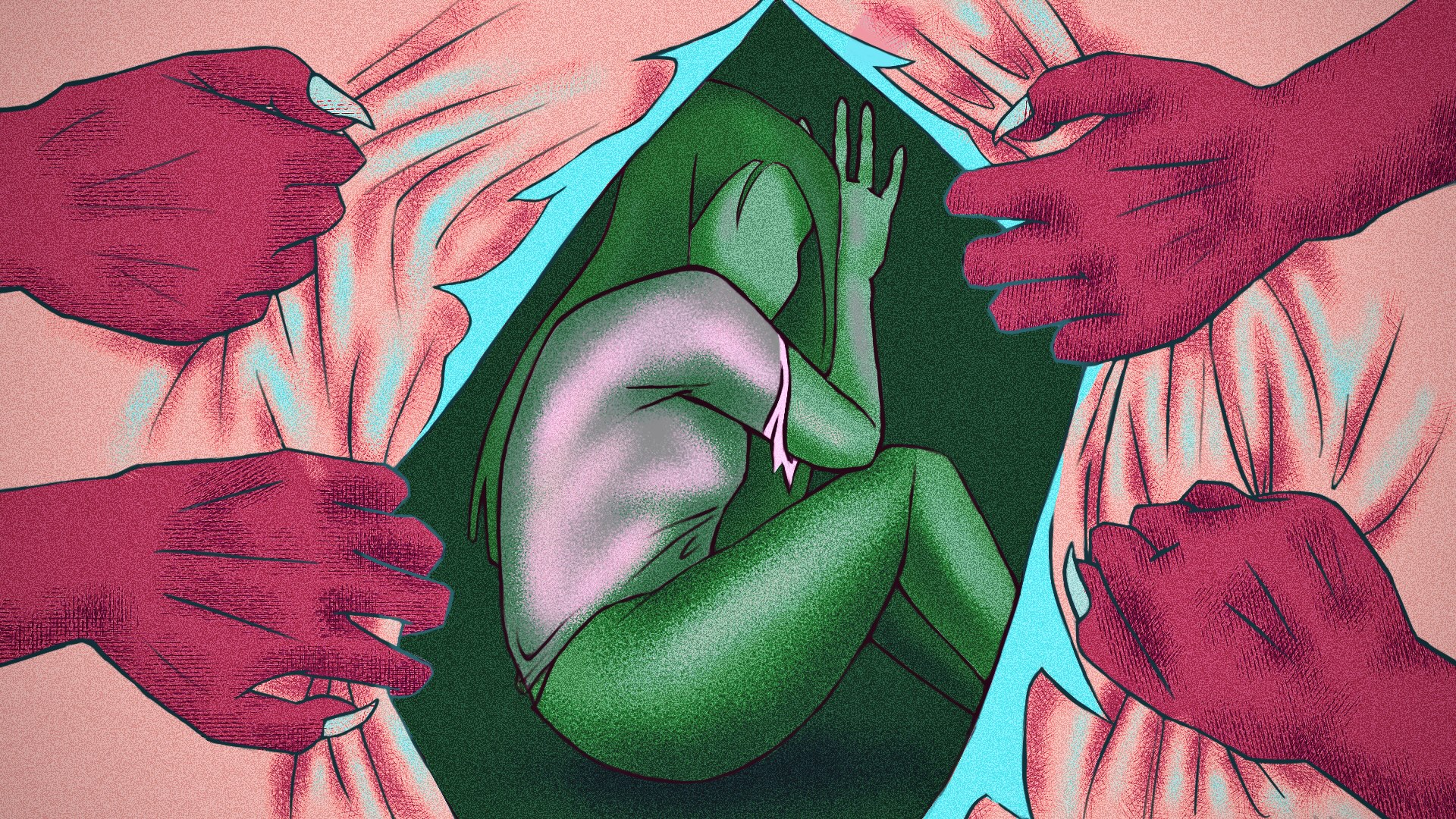

Warning: This article concerns several instances of rape and sexual violence.

On Sept. 29, a 19 year-old woman died of injuries after she was allegedly gang raped and physically assaulted by four men in a field in Hathras district of the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. She was a Dalit — people formerly known as “untouchables” who languish at the bottom of India’s harsh caste hierarchy. The alleged perpetrators are members of a dominant upper caste, Thakurs.

The victim, who had multiple severe fractures and injuries after the incident, lay in the general ward of a local hospital for more than a week before national pressure started building up. After her relatives pleaded with the doctors to attend to her, she was moved to the ICU and was later shifted to Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital, where she gave her dying statement in which she reportedly named four men — Sandip Singh, Ramu Singh, Ravi Singh and Lavkush Singh, who have since been arrested. She spent two weeks fighting for her life in the hospital from severe damage to her spinal cord.

The night she died, the Uttar Pradesh police returned to her village with the body, and instead of handing her over to her mourning family, the police insisted she be cremated right away, the family has claimed. However, when the family refused because they wanted time to say goodbye, the police locked them in their home and took the girl’s body to a nearby field and burned it in the middle of the night without the family’s consent. A Delhi journalist who happened to be at the crime scene witnessed it, Tweeted about it and that’s when the case garnered national attention.

Two days after the incident, another Dalit woman died after a gang rape in Balrampur, Uttar Pradesh.

There is a set script that has been accompanying the rape of Dalit women since time immemorial. She is desired, taunted, looked down upon, disregarded, abducted, raped and brutally murdered. She is stripped of the tiniest shred of her dignity. In life and in death, her lifeless body is tossed in the Dalit ghettos to silently accept the hell unleashed on the community everyday. And if, by any chance, one in a thousand cases gets nationwide attention, the victim’s character is assassinated. If that plot doesn’t fit, her family is implicated in her death. This template isn’t new or unique though. The Hindu Rashtra — a la Upper Caste and Upper Class Banana Republic — is known for upholding this pattern for a very long time.

It took place in Khairlanji, Maharashtra, a state in Western India when a Dalit woman dared to raise her voice against a group of dominant upper caste members for a small piece of land. The entire village participated in the gang rape and murder of Surekha, and her daughter and her two visually disabled sons. And when it received media attention, the caste solidarity working in the higher offices in Delhi shielded the perpetrators.

It happened to Bhanwari Devi, a voluntary worker with Rajasthan’s Women’s Development Program (WDP), who spoke out against child marriage and then met the wrath of the upper castes. In opposition, a group of upper caste men gang raped her and attacked her husband. Her case garnered nationwide attention and led Vishakha, a non-government organization that fights for women’s rights, to take on and fight her case. This culminated in the forming of Vishakha Judgement and guidelines to protect women in their workplaces throughout India.

However, the law that was inspired by the case of a Dalit woman failed to safeguard other Dalit women, like the 19-year-old girl in Hathras or the 22-year-old in Balrampur. Or every other Dalit woman, every day.

In its annual report the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) of India stated that India recorded 88 rape cases every day in 2019. Of the total 32,033 cases reported that year, 11 percent happened within the Dalit community; 3,500 Dalit women were raped in 2019, which is a spike of 18.6 percent as compared to the numbers from 2018.

In simpler words, 10 Dalit women are raped everyday in India. And these numbers only reflect the officially reported data.

When India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi started his campaign for 2018, he vowed “zero tolerance” of violence against women after the gang rape and murder of a 23 year-old paramedic student in the capital city of Delhi in 2012 shocked the nation. But even though less cases of rape have gone unreported since then, India is currently the most dangerous country in the world in which to be a woman.

And in between these alarming numbers lies the relationship between caste and rape. Overlay this data with misogyny among Indian men meeting caste bigotries, and the situation looks even more grim for the Dalit community.

The National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ) report this year stated that crimes against Dalits have increased by 6 percent between 2009 and 2018.

“Dalit women often bear the brunt of violence at the hand of dominant caste; violence as grave as physical violence, sexual violence and witch branding. In the Covid-19 pandemic also, Dalit women witnessed various forms of atrocities… In the last five years, 41,867 cases or 20.40 percent were related to violence against Scheduled Caste women,” the report stated.

Even the NCRB confirms the trend of crimes against Dalits. In fact, it registered a surge in such crimes every year between 2013 and 2018 after the Modi regime took over the country.

What does the Hathras case highlight? Crimes against Dalits and indigenous tribal communities — including rape — do not take place out of the blue, nor are they a current trend. These injustices have strong roots in age-old discrimination and cases of insults and assault against Dalits at the hands of dominant castes over issues like land or water or access to public spaces or even out of their own bigotry, creating a space in which the upper caste can attack Dalits and enjoy impunity.

This inequity demonstrates to every Dalit that upper castes can get away with any atrocity because the administration is “on their side.” Hardly any atrocity faced by a Dalit makes it to the front page unless something as ghastly as the Hathras incident happens. Then suddenly, the journalists on ground take note of nearly 18 rapes or gang-rapes in two days after the incident. And the cycle of forgetting repeats.

But behind these sustained and heinous crimes is a message: Atrocities against Dalits are a mode of teaching a lesson to the entire Dalit community.

In his analytical book, “Khairlanji: A Strange and Bitter Crop,” Dalit scholar and professor Anand Teltumbde (who is now accused of Maoist links and has been imprisoned) wrote about why these cases of extreme brutality on Dalits, especially women, are not “isolated events” or “just misdeeds of some uncultured barbaric monsters.” He noted that violence against Dalits, especially rape, is a functional and systematic way of enforcing social order, which is why it is “performed as a public spectacle by collectives.”

“Rape is not a private affair,” he wrote. “It becomes a celebratory spectacle. Atrocities involve intricate and devious planning so that they become a ‘lesson’ for the entire Dalit community.”

A close examination of the cases of sexual assault and violence against Dalit women prove Anand’s point true and bare an ugly pattern of impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators.

In the case of Bhanwari Devi, the perpetrators were acquitted in 1995 and the judge during trial noted that “rape is usually committed by teenagers, and since the accused are middle-aged and therefore respectable, they could not have committed the crime. An upper-caste man could not have defiled himself by raping a lower-caste woman.”

The Hathras case reeks of strong similarity to the Bhanwari Devi case and has yet again exposed the lack of accountability in the justice system vis-à-vis Dalit women.

What happened in Hathras is a continuation of what happened to Bhanwari Devi in 1992 or what happened to 8-year-old Asifa in 2018. The Hathras case went a step further with the state-sponsored propaganda that ‘no rape was committed’ simply because the forensic report revealed the absence of semen on the body of the deceased.

It’s no coincidence that the state (Uttar Pradesh), which leads in crimes against women, also ranks highest in atrocities against Dalits. These lines run parallel. A caste-based society which firmly believes that it has all the right to be violent against Dalits will attack women and children at its first chance as these are the groups that are the most vulnerable. And since the upper-caste Hindus are assured that they will anyway enjoy all impunity, especially if it’s them vs. a Dalit or tribal woman, they practice their will and hatred as and when they want to.

This is why, despite constitutional safeguards as well as special legislation like the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act of 1989, the rights of Dalit women and other minorities continue to be violated and they still stand extremely vulnerable to sexual assaults.

India has consistently failed to protect even the basic rights of Dalit women. Justice and accountability still remain a distant dream for them. The exemption of their human rights and the naked abuse of law and protocols are so evident in the Hathras case that it makes one wonder about the everyday struggle of a Dalit woman.

The fearless sanction of inhumanity by the state, the sheer negligence by those upholding law and orders, and the disgusting impunity provided to the Upper Caste men in this case — and every case against a Dalit woman — show why the systemic oppression and violence faced by Dalit women is incomparable and far more painful and traumatic than that of non-Dalit women in India.

Nice Article.